‘ Mr. Crossman spends much of his spare time writing and is a frequent broadcaster on the BBC European and American services. That he can concentrate freely on so many public duties is in part due to his wife's constant help in making small things run smoothly in answering the telephone, driving the car, typing, and entertaining…‘Standing by with a cup of tea’ is how Mrs RS Crossman, wife of the Member of Parliament for Coventry East, laughingly described the life of an MP’s wife when I met her last weekend.’

The Coventry Standard, 11 September 1948

Most of my current research is concentrated on a group of politicians’ wives who, in the 1960s, demonstrated that being married to an MP, or even to a busy Cabinet Minister in the Labour Government, did not mean being confined to the shadows - to ‘standing by with a cup of tea.’ But it is refreshing for us to be reminded, as this piece from the Coventry Standard does, just how difficult it was to escape from the stereotype of the good little wife waiting on her MP husband with a myriad of unpaid and unappreciated small services. Zita Crossman had been the wife of a sitting MP since the July 1945 election swept her husband Richard, or Dick as he was commonly known, into power alongside 392 other Labour MPs. According to the interview she gave to fill the column of ‘The Woman’s Angle’ in this constituency newspaper, she had already tired of sitting in the House of Commons watching proceedings, preferring to catch up by reading Hansard. The tragedy is, that this was so very different from the life she had envisaged when Dick first stood for Parliament, when she planned that they would be ‘brothers in arms’.

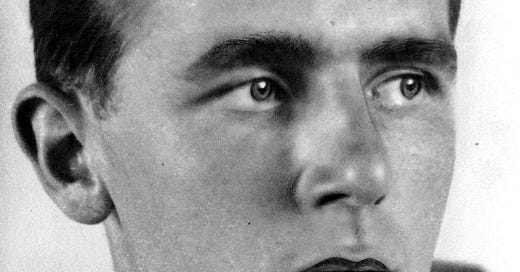

Zita was not Crossman’s first wife. In 1931, with an Oxford First in Classics under his belt and a Fellowship in New College beckoning, Dick set off to spend a year travelling in Germany. Here he fell under the spell of a woman several years older than him and already twice married, called Erika Gluck. In December 1931 he brought her home to meet his parents (his father was a High Court Judge) and although at first things went well, when Erika fell ill and a doctor was summoned, it became clear that her problem was drug-related. The pair were thrown out of the house: if anything could have made up the rebellious Dick’s mind to wed Erika, this was surely it. They were married in Oxford Register Office in July 1932, with witnesses from the staff of New College and a blessing afterwards in the College chapel. However, within a few weeks the marriage ran into trouble. Sir Isaiah Berlin, one of Crossman’s pupils, later told Tam Dalyell that Erika was ‘almost certainly unbalanced…dancing on the table at college occasions, screaming ‘Ich bin kleine Erika’ was a little much even for Oxford in the early 1930s’.

Within the year Erika, the flamboyant, troubled, Communist, had returned to Europe, ‘she left for a skiing holiday and never came back’, according to family legend. It took Dick some time and several trips to track her down and obtain a divorce - for he had already made up his mind to marry again. If Erika had proved a problematic choice, the circumstances surrounding his relationship with Zita were no less tricky. She was married already, with two young children, to one of Crossman’s fellow dons at New College, the zoologist Ian Baker. Crossman cannot be blamed for the failure of the Baker marriage: Zita (short for Inezita) had previously embarked on an affair with a much younger man, Tom Harrisson, on a geography field trip with her husband to Borneo. The details of this love affair were poured out in letters to her best friend in Oxford, the writer Naomi Mitchison. However by 1934, when Dick met her, she was living quietly back at 94 Woodstock Road with her two children and her husband. She and Dick bonded over her secretarial skills: Dick was combining his Oxford teaching with journalism for The Spectator and The Economist. He was aware that he was not her only lover, but she had become intrigued by his possibilities as an active Labour Party politician. She wrote to Dick

I went to the Oxford City Labour Party meeting last night and had some good fun over you. When the question of a Parliamentary Candidate came up, they read out three that had been recommended by HQ - all very dull. Then I got up and proposed you, putting forward all your assets in very glowing terms. I didn’t give them to understand that you would certainly accept but that, if approached, you might consider it very seriously…Eventually it was decided to ask both you and Gordon Walker to meet the party and then a choice would be made…By the way, I don’t believe you are a member of the party so I made you one and paid 10/- membership fee.

According to his biographer, Anthony Howard, ‘it was not the least of Zita’s contributions to his career that she, above anyone else, was responsible for turning him from the outsider, ‘bolshie’ don into the loyal - though hardly ever orthodox - Party member.’ It was with her encouragement that Crossman began to become a well-known figure outside Oxford academic circles, delivering a series of very well-attended lectures entitled ‘How Hitler came to power’ - drawing on his experiences in Germany earlier in the decade. Zita and he began to discuss the idea of forming a working socialist partnership: when Crossman wrote to her ‘I can be a really great man but I haven’t started yet. I’ve got the vitality and the brains but not the stuff - so it’s all a bit hollow really’, she replied

I’m damn glad that you’re not content with being a professional public speaker. You could do that easily and well and make pots of money and be so respectable. I’m glad you feel the hollowness inside you. That’ll get filled up a good deal with me and what I give you…

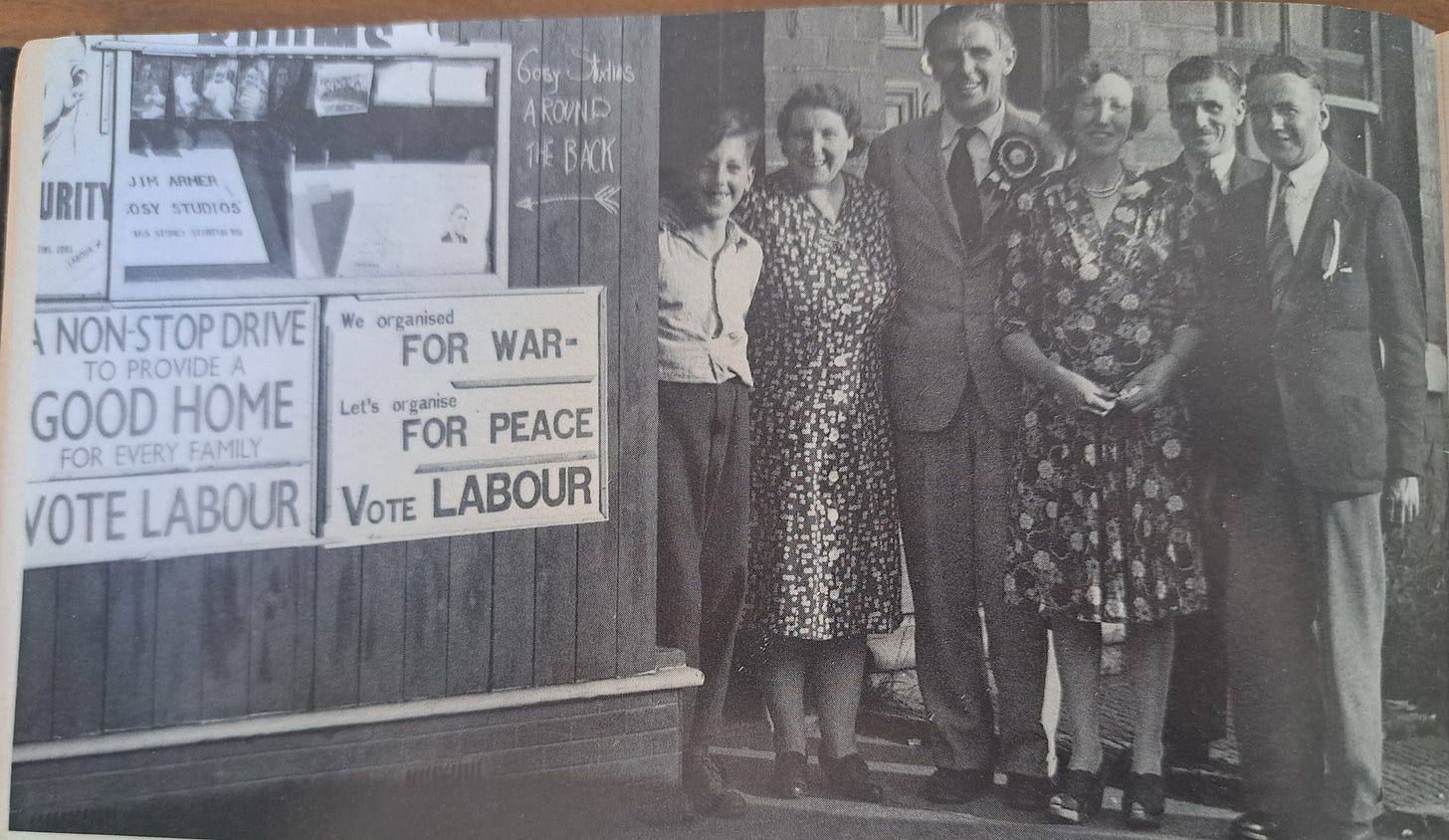

Later in 1935 Crossman was elected to Oxford City Council and became Leader of the small group of Labour councillors. His career in politics had begun, with Zita pushing him all the way. Their affair was still a closely guarded secret: Zita even underwent an illegal abortion for fear of compromising her lover’s career.1 However within a year Ian Baker demanded a divorce, and planned to name Crossman as the co-respondent. Somehow Dick persuaded one of Zita’s earlier lovers, a shop steward in a factory in Cowley, to take the blame. Of course all the misery now fell on Zita, just as it would on Mary Stewart a few years later2 - she had to leave Oxford and avoid any possibility of being linked with another man while waiting for the decree absolute. Interestingly, she decided to join her former lover Tom Harrisson, in Bolton, where he was setting up the Mass Observation survey. Most irritating for her of all, was that she missed the chance to help Dick fight a by-election in West Birmingham, something she had been encouraging him to attempt since their affair had begun. He wrote to her ‘It is horrible your being left out of this but there will be lots of elections in our lives, I rather think.’

West Birmingham was a hill too high to climb, but the promising result achieved by Crossman in reducing the Conservative majority led to him being offered the next vacant seat in Coventry. However, the Warden of New College was infuriated that Dick had gone to the Birmingham fight without getting any permission or even giving notice, and this combined with rumours of an affair led to Crossman having to resign his Fellowship. He and Zita were married in December 1937. Dick was thirty, Zita claimed to be thirty-four on the marriage certificate - she was actually thirty-seven, a fact that eluded Dick until after her death.

For the next couple of years Crossman built his career as a journalist at the New Statesman: when war broke out he was seconded to Military Intelligence and became a major part of the clandestine propaganda activity aimed at the people of Germany. By 1945 his title was Assistant Chief of Psychological Warfare. It kept him busy and often tied him to London: Zita took responsibility for keeping his name remembered in Coventry. This included a visit she made to the City the day after the appalling saturation bombing attack, and she represented Dick at the May day celebrations in 1945. But they had spent many months apart, and Zita had also missed her children, who had been sent to America for the first four years of the War. No sooner had Dick been elected than he was selected by Attlee to join the international commission on Palestine which involved a great deal of travel, including several rather luxurious trips to the States where he wrote tactlessly to Zita of all the lovely food he was eating. It had always been her aspiration to share his work: it was proving frustratingly impossible.

In the summer of 1948, Dick and Zita rented a house in Vincent Square, close to Westminster. This would be the Crossman family’s London home for the rest of Dick’s life, and its convenient location ten minutes from Parliament meant that it served as a meeting place for the various members of the Keep Left clique - Zita must finally have felt she was able to take the role she had always wanted, as a political hostess, and a participant in many crucial debates and plots with the Bevanite young turks, including Barbara Castle, Harold Wilson, Michael Foot and Ian Mikardo. They met for lunch at 9 Vincent Square every Tuesday, chipping in six shillings and sixpence each to cover the costs. With her children now off her hands, Zita took up voluntary work at a Family Planning Clinic in North Kensington, and at Lambeth Children’s Hospital - where in July 1952 she collapsed with a cerebral haemorrhage - she never recovered consciousness and died in Westminster Hospital. Attendees at her funeral included Nye Bevan and his wife Jennie Lee.

Richard’s third wife was fourteen years his junior, but he had known her since she was a girl. In the 1930s, when he was a young left-wing don, he had often visited Prescote Manor, north of Banbury, the guest of AP McDougall, an anti-Tory farmer and founder of Banbury Cattle Market. Anne, his only child, always said that she had known as a teenager that one day she would marry this glamorous, handsome man.

During the war, an Oxford graduate, she had served at Bletchley Park and afterwards she worked as secretary to Maurice Edelman, another Coventry MP. Dick and Anne’s engagement was announced in January 1954. On their marriage, the 360 acre farm was gifted by her father to the couple, causing a great deal of ribbing as the left-winger became, in his own words, ‘that wicked thing, an urban gentleman farmer.’

Dick and Anne were happily married for twenty years, and had two children. She was perhaps the least politically motivated of his three wives, but yet was capable of holding strong opinions. Tam Dalyell, who knew her well, wrote:

Anne was not an interfering wife. But I thought she was a powerful and benign influence. Certainly on a number of issues she made her views known, and one of those views was that the Labour Government in general, and the Secretary of State for Social Services in particular [ie her husband!], should jolly well do something for the mentally ill. Politicians (I am another) who have wives with a fierce sense of right and wrong had better take those views into account. Anne thought that the mentally ill deserved special consideration, particularly because they had no clout politically.

Anne was kept busy running the farm which rapidly expanded under the couple’s stewardship. She also produced two children, Patrick and Virginia, who were a special delight to their father. When her husband received his diagnosis of the terminal cancer that would kill him in 1974, Anne encouraged him to complete his ambition to prepare his voluminous diaries for publication. Richard Crossman died on 5 April 1974, and the legal struggle to get the diaries into print, despite fierce opposition from Whitehall, and from Prime Minister Harold Wilson in particular, consumed much of her time. Her misery must have been compounded by the suicide of her seventeen year old son less than a year after Dick’s death.

The Diaries were a publishing phenomenon, serialised in The Sunday Times and selling thousands of copies. Anne used the proceeds to refurbish a barn into an Arts and Crafts Gallery and cafe. She died in 1988.

It is fascinating to ponder what Zita might have gone on to achieve if she had not died so suddenly and so young. She was responsible for transforming Crossman from a ‘Bolshie’ don with opinions, into an active and campaigning politician. Richard Crossman was one of the towering intellects and personalities of the Wilson Cabinet, although not always its most popular or clubbable member. Zita was just beginning to find a role for herself with her voluntary work, and as part of the network around the Labour Party in the 1950s might well have found herself with something more inspiring to contribute than ‘standing by with a cup of tea’.

This piece has primarily been compiled from the biographies of Richard Crossman by Anthony Howard and Tam Dalyell.

This was confirmed by two independent sources to Anthony Howard. Sadly the procedure may have been physically damaging, as Zita and Richard were never able to conceive together again.

Fascinating stuff. Years ago the story within the Labour Party was that you never invited Dick Crossman to anything on a Saturday night. If you did he would bring his slippers and demand to watch the football.

Another fascinating piece. What an extraordinary group of women you are uncovering.