In March 1944, a WAAF officer stationed at RAF Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, began to keep a diary. Reminiscing about a brief period spent in Manhattan before the war, and the beauty of the lights of Broadway at night, she wrote:

The only sight comparable to that moonlit fairyland was central London burning in the moonlight during the London Blitz. Kelly and I watched it one night from a Lamb’s Conduit rooftop onto which we had climbed in a chase after incendiaries - or rather Kelly chased the incendiaries and I chased Kelly as I was too scared to remain in the street by myself. We were trapped for a time on the rooftop - a house in the row was hit so exit was barred to us and we couldn’t at first find a skylight open in the other houses. Bombs whistled over us and we had to cling to the chimney pots lest we were blown down by the blast.

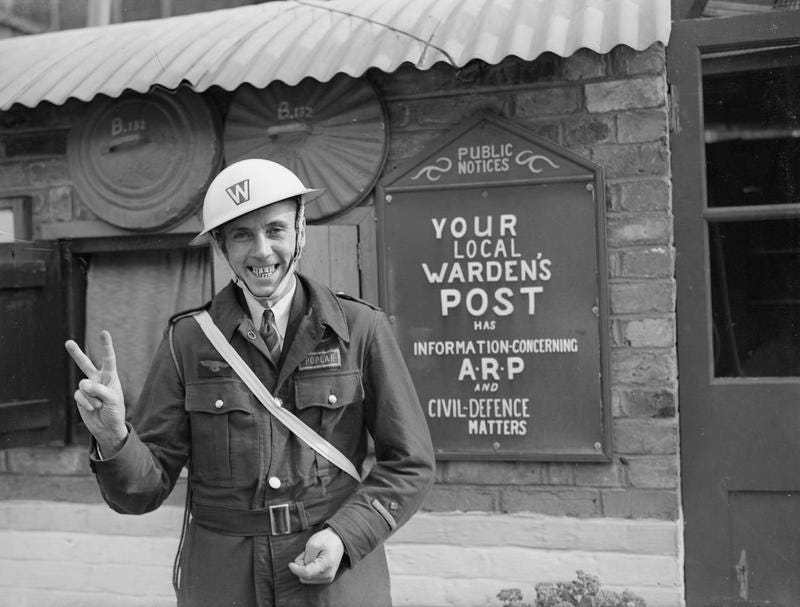

Mary was the Senior Marshall for an air raid shelter based, from what I can gather, somewhere in or near Tavistock Square, and as an Air Raid Warden she also had the duties of what we would now call a ‘first responder’, patrolling the streets, putting out the fires caused by incendiary bombs, and assisting the Fire Brigade and the ambulance service to locate and look after casualties.

In a quiet moment I looked over the parapet onto the road below and thought how odd it was that I who normally had a terror of heights should be so calm on this one. And then I looked up and saw the moon shining down on us, quite unconcerned by the screaming bombs and crashes and the intermittent hum of the bombers and the immense fires surrounding us. I thought I was going to die and I wasn’t afraid.

Mary was 36 when war broke out, and living in central London. At the time of the Blitz in 1940 she had just become engaged to a man she had known for some time; Michael Stewart was a couple of years younger than her, and had pulled himself up from Brownhill Road Elementary School in Lewisham, South London, via a scholarship to Christ’s Hospital in Horsham, Sussex, and on to St John’s College, Oxford where he read PPE. Clearly destined for a starry political career, he took a First, while also serving as President of the Oxford Union and as chairman of St John’s Labour Club. Mary and Michael met in 1934 when they were both lecturing at a Workers’ Education Association (‘WEA’) summer school. In 1940 he was teaching at a boys’ boarding school, the Coopers’ Company’s School, which had been evacuated from London to Frome in Somerset.

And then Kelly broke open a trap door and jumped several feet and helped me down after him and soon we were in the street again. I thought we should go straight back to the comparative safety of the post - but that wasn’t Kelly’s way - he always knew where he was needed. Taking my hand he strode along to a street in which a house was on fire - without stopping to question one or two people standing in the road he walked straight down the basement steps and came back a few minutes later with an elderly man and woman who either lived there or had been sheltering there. Meanwhile another packet of incendiaries clattered harmlessly into the roadway.

I don’t think I could live those days again.

Mary was the daughter of a commercial traveller, Herbert Birkinshaw, and Isabella Garbutt. The family moved to live just south of Birmingham when she was four; she was educated at King Edward VI High School, and then went on to Bedford College, London where she studied philosophy. She also spent a year in Southwark working with the Women’s University Settlement, and became interested in social studies. By the time war broke out, she had a full time career lecturing in psychology and sociology for the WEA, which involved a great deal of travel. She continued to pursue her interests as an academic, working occasionally at Guy’s Hospital, and in 1939 visiting New York and studying with a team of psychologists there, a time she later looked back on with enormous pleasure. She also became involved in the Fabian Society, teaching at weekend and summer schools, and these shared socialist interests helped to kindle the romance with Michael - a man who had thought he would never marry, according to their letters.

Mary wrote regularly to Michael in Frome during 1940 and 1941, and from her letters we get a glimpse of wartime life in London. The letters date from April 1940, just after their relationship of six years had changed dramatically, and apparently surprisingly, from friendship to love. But this was not a sexual affair: Michael had his political career to think of, as he was determined to win a seat as a Labour MP after the war and was already the candidate for a seat in Fulham, west London. Neither he nor Mary wanted to risk any scandal that could damage the constituency, his teaching position, or the WEA where they were both active members. They certainly needed to exercise caution, because Mary was already married. Robert Goodyear, known as Bob, had married Mary Birkinshaw in 1931. Wikipedia describes him as an advertising clerk, but he was also a less than successful novelist, moving on the edge of the circles around EM Forster. His last of four novels, Mrs Loveday, was published by Victor Gollancz in 1944 and dedicated to Mary. However, by 1940 Mary had left Bob, and was sleeping on a divan in a flat in Millman Street, WC2, rented by her friend Mollie Hobman, a journalist and film critic.

Mary’s determination to end her marriage and be free to wed Michael required her to obtain a divorce, something that was exceedingly tricky for a woman in the 1940s: luckily Bob was happy to oblige, and to take the necessary blame as the adulterous party. Nevertheless, there was an anxious time for Mary to wait, perhaps six months, before the decree absolute could be granted, during which time a Court official, known as the King’s Proctor, was charged with ensuring that Mary was not equally adulterous. As she wrote to Michael ‘I may have men friends - go out with them - but may not be alone with one in a place in which adultery could be committed. Mollie says gloomily that she sees that her summer will be fully occupied with chaperoning me. I wish I knew what the King’s Proctor and his friends looked like…'

The divorce finally came through in May 1941, and Michael and Mary were married quietly in London two months later. But Michael was still teaching in Frome, and Mary continued to combine her WEA lecturing responsibilities, travelling across Essex to Benfleet and Southend, with her duties as an air raid shelter warden. London was a desperately miserable as well as a dangerous place to live: in January 1941 Mary wrote to Michael ‘I walked through the City this afternoon. The sightseers were so quiet and sad. It was like being at the funeral of someone you had loved very much. St Paul’s, standing blackened but unharmed amidst the ruins, seemed grander and more important than ever.’

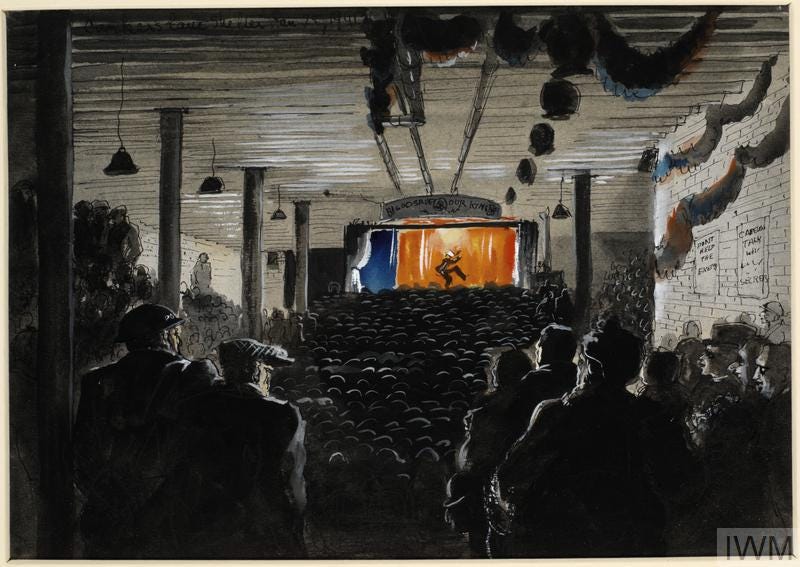

Her role as the senior marshall at the shelter, where over 100 London citizens hid from the bombs at night, required enormous reserves of determination and organisational skills: one day she found a woman lying in a bunk clearly suffering from diphtheria: it took Mary hours to find her an ambulance, and even longer to persuade the authorities to remove and burn the bedding. On 18th April 1941 she reported London’s heaviest raid to date: 1,000 killed, 2,000 injured. In Holborn, her district, 152 High Explosive bombs fell and five landmines. In her sector alone there were eight bombs, four fires which required the fire brigade, and 48 smaller fires they dealt with themselves. There were no casualties in her team, but six wardens were killed across Holborn. Altogether across the country some seven thousand civil defence workers were killed in the War.

Mary enjoyed the camaraderie of the ARP wardens in the Blitz, such a mixture of ages, class and background. To avoid controversy, her group avoided conversations about politics, sticking to personal gossip. The team at her post comprised ‘a butcher, a housepainter, a street bookie, a lawyer, a woman journalist, a woman novelist, a nightwatchman, a teacher, a clerk or two and an ex-clergyman. We have little in common save our preference for death rather than Nazi rule.’

This list fascinates me, particularly the mention of a woman novelist. By this point she and Mollie had moved on, possibly bombed out, from Millman Street and were in rented rooms at 10 Mecklenburg Square: this is the Square which was the subject of Francesca Wade’s fascinating group biography, Square Haunting - between the wars it had been home to Dorothy L Sayers, Jane Harrison and even briefly, in 1940, Virginia Woolf. I’m not suggesting that any of these distinguished women were part of Mary’s ARP team, but it is nevertheless intriguing. I have also discovered, from Lara Feigel’s The Love Charm of Bombs that the novelist Elizabeth Bowen was an ARP warden in Marylebone, and even more crucially, Grahame Greene and his lover, Dorothy Glover, were living in a flat in Mecklenburg Square in 1940 and were both volunteering as Fire wardens. Dorothy at this time was a theatre set designer, but she and Grahame were playing at writing together: was she the ‘woman novelist’ based at Mary’s post?

Meanwhile, Mary remained fascinated by the character of Kelly, the leader of the team. She discovered that he had grown up on a farm in Australia; he is the ‘street bookie’ mentioned in her list.

Kelly is the finest person I have ever met, he is so genuine, so selfless, so brave, so gay and friendly in peaceful moments and so alert and detached in hot ones. In the past I have tended to despise brave people because so often they are insensitive and thoughtless. Kelly’s bravery is of a different order. He is never stupid, never thoughtless. He would sacrifice his life for anyone at our post, and of course for the people in our sector, but he expects us to do the same. If he had to choose between the life of a warden - even one he loved - and one or more of the householders or shelterers in our sector, he would sacrifice the warden…Twice on Saturday night when he protected my body with his own from the blast as we crouched in the roadway, I thought dying with him wouldn’t be so terrible after all.

In May 1940, after the fall of France when everything seemed very bleak, Mary wrote to Michael ‘It seems wrong of me to hope as much as I do that we shall both survive this war and help build the foundations of the new world. It’s like asking for a special privilege for us, when we know how many people must die.’ At the end of 1941, six months after their marriage, both Mary and Michael enlisted, and for the rest of the war they were rarely in the same place at the same time. Next week I will write about Mary’s life in the WAAF, the Women’s Auxiliary Airforce, and how her married life developed after the war. Surely her experiences in the war, her time as a WEA lecturer, an ARP Warden and in the WAAF, had an influence on how she and Michael would view life, society and politics in the years leading up to the 1964 General Election.

Spoiler alert: By the time Mary died in 1984 she was Baroness Stewart of Alvechurch, created in her own right. Her husband Michael was a distinguished Foreign Secretary in the first Wilson Government. She is, of course, one of my dahlias!

I’m particularly grateful to the Churchill Archives Centre which holds the Michael and Mary Stewart papers (Reference Code: GBR/0014/STWT) for all their help. I have only explored a tiny proportion of the material in the research for this Substack, and hope to go back for more at a later date!

Enthralling writing, as ever, and again introducing me to someone I had not previously encountered. Thank you!

I love to read stories about how real people manage to carry on a "normal" life even when circumstances scare them out of their wits.