Now there was a time

When they used to say

That behind every great man

There had to be a great woman…

(Lyrics by Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart)

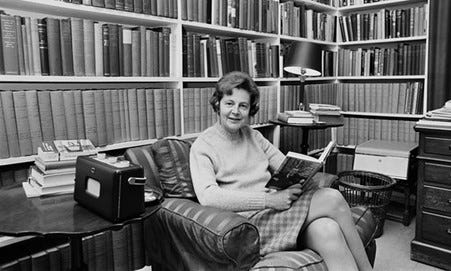

For the last year, I have been pulling together the research for what I hoped would be another book. Literature for the People was a wonderful five year project, and luckily, as anyone who has read it will know, I rather fell in love with Alexander Macmillan, which made him a pleasure to write about. But the first book I wrote, which failed to find a commercial publisher, was about a woman, a relatively unknown Victorian painter and illustrator, Nelly Erichsen, and of course we all know that there are plenty more women out there who deserve to be better known. Still, there is a problem: as the wonderful biographer Edna Healey puts it, in her work Wives of Fame:

The figures of the great, who loom so grandly in the halls of fame, appear to stand alone. But shine a light into the darkness and slowly dim outlines emerge behind them. Few men achieve greatness in isolation. Somewhere in the background is a colleague, a sister, or even a housekeeper or valet, without whom they could not have endured the stress and loneliness. But often there stands a wife, invisible and forgotten, whose name is not recorded on the tablets of bronze and of whose famous husband it is so frequently said: ‘I didn’t know he had a wife.’

There were two particular ‘wives’ who I already admired and wanted to know more about before I started this project: this same Edna Healey, author and wife of Denis (the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974-9), and Mary Wilson, poet and wife of Harold (the Prime Minister 1964-70 and 1974-6).

As I started to research these two women, it occurred to me that they had much more in common than just their husbands’ public profiles. Something that made them uniquely interesting. The women who were born in Britain in the first two decades of the twentieth century, as Edna and Mary were, formed a very particular generation. With markedly different life expectations from all the women before them, they found themselves facing a uniquely challenging young womanhood. Unlike their mothers and grandmothers, they grew up with the firmly-established right to vote and with an expectation that education, for bright working class girls as they were, would extend beyond school, into vocational training or even university. Thereafter they would be expected to find jobs and would, for the first time, see white-collar and professional careers opening up to them. The majority of young women would need to support themselves, at least until they married and possibly until they started a family. Then, as they moved through the 1930s and into the 1940s, these same young women found themselves in a world turned upside down, facing war and unprecedented levels of deprivation, danger and death on the home front. These were often the daughters of WW1 survivors, and now they had to watch the men they loved going away to fight, with their own marital, professional and domestic ambitions thrown to the winds.

I have become fascinated by the lives of one particular cohort of this generation of women: for shorthand, I initially thought of them as Wilson Wives, as all of them were married to men who served in one or other of the two Wilson Governments of the 1960s and 1970s. And why that particular group? Firstly, the Labour Government that came to power in the 1960s interested and inspired me. It had an enormous impact on the social and cultural life of the British people: the abolition of capital punishment, the end of censorship of the arts, the liberalisation of laws on divorce, abortion, homosexuality and women’s rights, the creation of the Open University, the outlawing of racial discrimination, the introduction of comprehensive schools…like it or loathe it, these Governments changed Britain, and I am intrigued by the personalities involved and what made them so open to cultural progress.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the wives of the men in the Wilson Governments were a completely different breed to the wives of the immediately preceding fourteen years of Tory rulers, let alone the pre-War generation. Many of these women came from working class backgrounds, and from non-conformist families. They did not grow up in privileged surroundings, with servants or attending posh schools: they had worked for a living, they shared their husbands’ Socialist views and campaigned alongside them. Above all, whether they were teachers, doctors, journalists, artists, writers or film makers, they did not let their husbands’ success hold them back.

The experiences of these particular women, as they came to adulthood in the 1930s and ‘40s, gave them ambitions and aspirations rarely seen in previous generations. Their determination to persevere publicly with their careers and personal interests, even as their husbands attained the most powerful positions in the country, would light a path for many more professional middle class wives and for future generations. For the first time ever, the Press regularly carried stories about career women who juggled family and professional lives, and they set an example for millions more girls and women across the country.

We are lucky in the West that women are able to pursue their dreams of independence and self-determination in this way: we should never take our rights for granted. I believe that the preservation of these rights requires us to commemorate, and celebrate, the lives of these women who blazed the trail.

Over the coming months, I plan to research as many of these women as I can and write about them on Substack. I am not sure it will turn into a book, but I still want to tell their stories. Where there are missing archives, perhaps no letters, no diaries, I may reach out to their families, and I will focus on what survives of what they achieved. Some of these women you may have heard of, many, I am sure you will not know at all. I’m hoping to start in a week or two with Mary Wilson, poet and friend of John Betjeman, perhaps the most reserved and diffident of them all. Along the way I will be looking at some of the political events and personalities that may have shaped these women’s lives, but also I will continue to share my background research into the world in which they lived: there will be Substacks about the books they might have been reading, the impact of the War, even the clothes they wore, or the ways they planned and managed their family life. My latest piece on The Left Book Club obviously fits this pattern, as would my pieces on the BBC in wartime, and the impact of The Spanish Civil War on young left-wingers at Oxford University.

Of course, I really hope I have convinced you that this is going to be worth following! Do let me know your thoughts. Also, watch out for a change of title for my Substack - it may be time to leave the Macmillans’ Crusade behind, although there will be a silver (red?) thread running through from the beliefs of the Christian Socialists, via the Fabian Summer School where Jennifer Morris first met her future husband Roy Jenkins, to the Beveridge Report and the ambitions of the 1964 Labour Manifesto.

I do have a thought about a new name, inspired by my morning wander down the garden to look at the last of the dahlias.

I’ve come late to dahlias as a gardener, but they are rapidly becoming one of my favourite flowers, overtaking the tulip and challenging the rose. They are late bloomers. I admire their pluck, that they continue to throw up new growth and flower buds even in November, with the risk of frost just around the corner. They don’t have scent to attract the bees, so they rely on producing the most extraordinary range of shapes and hues - any shade but blue, in fact. They grow slowly, and in the spring and early summer when all the other flowers are racing ahead, they concentrate on putting down roots, strengthening their stems, creating foliage for nourishment in the darker days of autumn, fighting off slugs and pigeons. And then, when they are ready, they produce the most stunning output of glorious colour. They need a collective noun, one of those that the English language is so good at, telling you something not just about the number, but about the feel of the thing. A pride of lions, a murmuration of starlings, a murder of crows. I’m thinking ‘an independence of dahlias’, or ‘a determination of dahlias’… And I think that my Wilson Wives (a name to which they would definitely have taken exception) have much in common with dahlias - late flowering, highly independent, brave, and any colour but blue….

So we're comin' out of the kitchen

'Cause there's somethin' we forgot to say to you, we say

Sisters are doin' it for themselves

Standin' on their own two feet

And ringin' on their own bells, …

Now this is a song

To celebrate

The conscious liberation

Of the female state

Mothers, daughters

And their daughters too

Woman to woman

We're singin' with you

…

We got doctors

Lawyers, politicians too

Everybody take a look around

Can you see, can you see

Can you see there's a woman

Right next to you…

This is a great project, Sarah. Look forward to reading more about these women.

You just reminded me of the wonderful, funny book, Great Housewives of Art by Sally Swain. Pastiche paintings of the wives of artists. Mrs Magritte Tidies the Hat Rack and so on. Obviously, that's very much off on a tangent, but like you, I so often read about famous men and am curious to know more about the women who supported them.

What a great idea, Sarah! I am looking forward to the posts. And the dahlias are quite the symbol. I like “independence of dahlias”!