Polly and Elwyn

A couple fighting for peace, justice, and for the Pearly Kings and Queens

Today’s post is about an extraordinary couple, active in British political and artistic life from the 1930s right through to the 1970s. Their names are not well-remembered today, you may never have heard of them, but their work and influence certainly live on. Have you been to see that wonderful, extraordinary film, Nuremberg? Elwyn Jones was there, one of the leading Counsels for the prosecution.

Have you spotted this beautifully produced book, Comrades in Art, by Andy Friend? Pearl Binder, Elwyn’s wife, features throughout. Next year at the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne there will be a major exhibition spotlighting her work, among others from this group of radical inter-war artists.

Elwyn and Polly could not have sprung from less auspicious backgrounds. Elwyn, born in Llanelli in 1909, was the youngest son of a steelworker, a chapel-goer and trade unionist, and was brought up speaking Welsh at home. Polly was born in 1904, the daughter of a Russo-Jewish immigrant, Morris Binderofski, who took British citizenship in 1911 and anglicised his surname to Binder. Morris worked as a master-tailor in Manchester and married a local girl, Janet Jacobs. They named their youngest daughter Pearl, but she chose to be known as Polly.

Of the two of them, Elwyn won the education sweepstake: from Lakefield Elementary School in Llanelli he passed the entrance scholarship to the County Intermediate School, where the headmaster, an Oxford graduate from Jesus College, encouraged him to join the Debating Society, to take his Higher Certificate and to study History at University College, Aberystwyth. From there he won a scholarship to Cambridge, sadly worth only £60 per annum towards a cost reckoned to be £250: his two older brothers and his sister funded the rest themselves out of their hard-earned pay packets. By 1930 Elwyn had become President of the Cambridge Union (I have read that he was the first state school President, but I cannot prove that - however I do know that his college tutor paid for the white tie and tails he required). With a stellar academic career behind him he was called to the Bar.

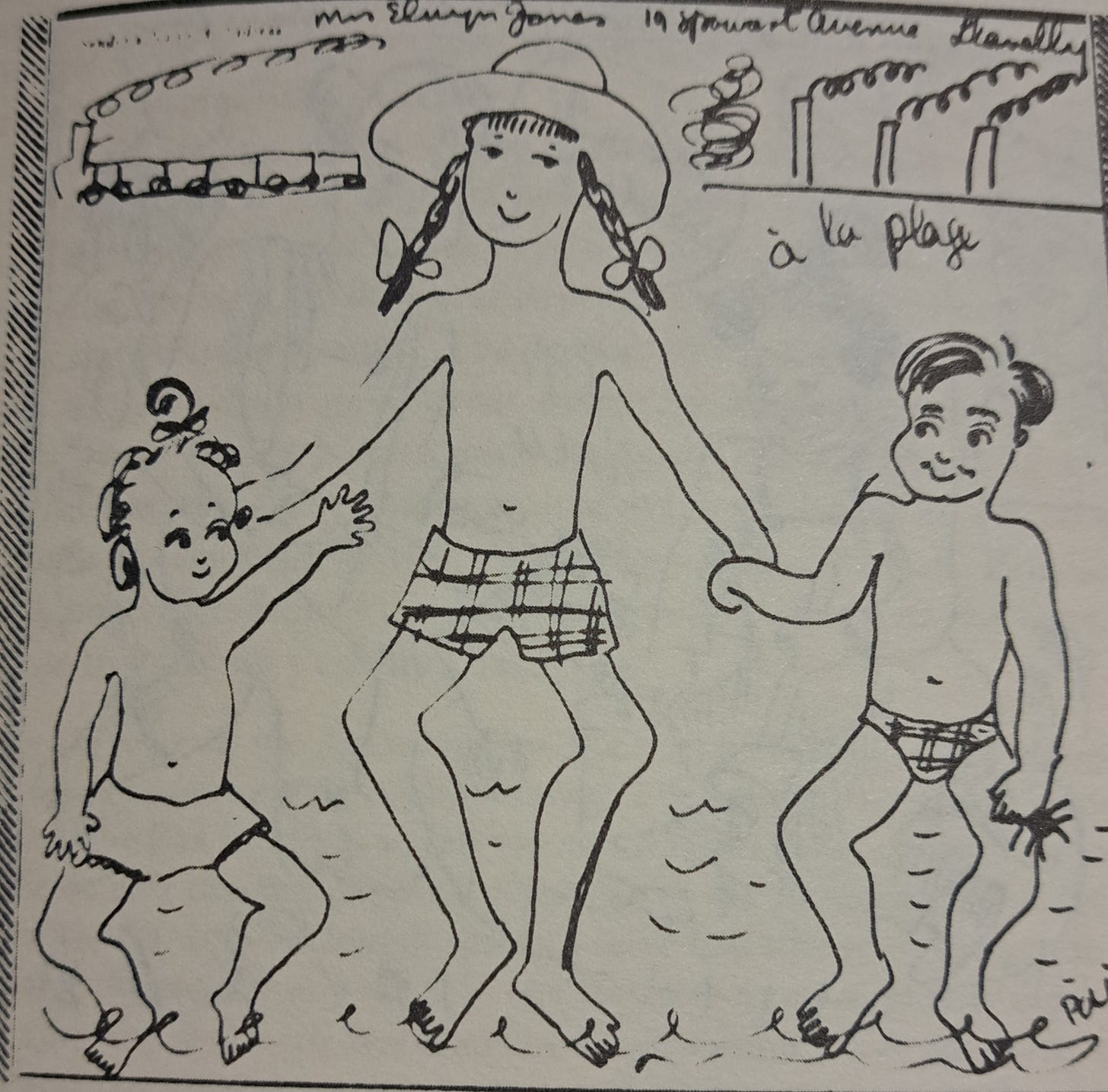

Polly’s education was a lot less glamorous. Coming from the back streets of Salford, she took a job clerking in a textile mill, but won a scholarship that enabled her to take evening classes at Manchester School of Art. Her abilities as an artist, and her fascination with textiles and fashion, would stay with her throughout her life. Her sketches, cartoons almost, were quirky, individualistic, and perfect for graphic reproduction. She moved to London at the age of twenty-one to earn her bread as a commercial artist and lithographer, and was briefly married to the anthropologist Jack Driberg, brother of the more famous Tom.

The early 1930s saw Polly and Elwyn both in London, struggling to earn a living in the Depression: Elwyn supplemented his meagre legal earnings with journalism and tutoring. He shared a flat in Mecklenburgh Square, where he lived next door to Richard Tawney, and then moved to Hampstead sharing with Richmond Postgate, brother to Raymond Postgate and Margaret Cole, pillars of the Fabian Society. (I have attached links to my previous posts on these people! Elwyn seems to be following my Substack subjects around!) By 1934 Jones was an active Fabian Socialist, and began to use his legal training in the increasingly murky waters of European politics - he went with Naomi Mitchison to Vienna to work on behalf of the prisoners locked up for being members of the Social Democratic party (SDP) - there were nine thousand people in custody, and Elwyn developed quite a reputation as the protector of the imprisoned.

Polly, meanwhile, was fiercely committed to even more radical politics, flirting with joining the Communist Party, while working on illustrations of conditions in the East End of London, including for Thomas Burke’s book, The Real East End (1932). She was living in Spread Eagle Yard in Whitechapel, and working on her own illustrated book of London lives, Odd Jobs. In July 1933 she visited Russia, taking with her a portfolio of her drawings: the rumour going round London was that the Soviets were happily employing commercial artists on propaganda missions and Polly needed the work. She arrived with a rucksack, a mackintosh, her portfolio and a little money, on a two week tourist visa: ‘Russia was to me a completely unknown continent…the best remedy for wishful thinking was to go to see for oneself.’ Of course, she must also have been aware that she was visiting her father’s homeland.

On her return, Polly was invited to address a gathering of young socialist artists in a flat rented by Misha Black: this was the foundation of The Artists’ International Association, described by Andy Friend as ‘one of the boldest and most imaginative artistic developments in England during the twentieth century’. By 1935 this had morphed into a specifically anti-fascist, popular front movement: ‘The AIA stands for unity of artists against Fascism and War and the Suppression of Culture.’ In November of that year an exhibition was curated featuring work by the artists involved (the membership had grown to over a thousand) and was sent touring factory canteens and provincial libraries around the country. Polly’s involvement in the anti-Fascist movement gathered pace when that same year she attended the ‘First International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture’, held in Paris, alongside EM Forster, Aldous Huxley and Andre Gide. A few weeks later, at a party to celebrate the launch of her book, Odd Jobs, she was introduced to the well-regarded and politically-active lawyer, Elwyn Jones. Polly filed for a divorce from her estranged husband, Driberg, and the couple were married in October 1937.

Polly took a job in advertising, and then went to work for the BBC at Alexandra Palace, preparing talks for broadcast on the newly launched television network. Their first child, Josephine, was born in January 1938, but Polly continued to work, hiring a live-in housekeeper and a live-in nurse. She was probably the first heavily pregnant woman to appear on British TV. Their flat in the Goldsmiths Building over looking the Temple and Oliver Goldsmith’s grave was increasingly crowded - and in January 1939 they rented a large run-down house in Hounslow.

We pushed open a handsome but creaking wrought iron gate and walked towards the front door of the house. The tangled lawn was matted with dead leaves and covered with white frost. I dug in my walking stick and lifted the frozen crust. Underneath were clusters of snowdrops in bloom. That decided us. We took the house.

Before long, the household would increase further when the couple took in Margit, a teenager from Germany, rescued under the KinderTransport scheme. In 1939, Elwyn joined up, and by 1940 he was in Kent.

Early in September 1940 my troop was stationed in Manston Aerodrome, just a few miles out of Dover. The German Panzer army was on the French coast just across the Channel. One beautiful moonlit night I was summoned to report at once to the RAF Station Commander. I chugged across the aerodrome on my power-driven pushbike. He informed me that … weather conditions for an air and seaborne invasion were perfect and that my troops should be ready for action an hour before sunrise.

‘How long can your guns fire?’, he asked me.

‘To the last round, Sir.’

‘And how long will that be?’

‘Seventy-five seconds, Sir’. I explained that I only had 150 rounds for each of my three Bofors guns and that they fired 120 rounds a minute.

‘Where do you get your reinforcements from?’, he asked me.

‘Dover Castle’

‘Do you realise that the Nazi paratroops are going to drop between here and Dover?’

‘I mentioned this to a brigadier, when he came round recently,’ I explained; ‘but he said it was none of my business.’

Extract from In My Time, the autobiography of Lord Elwyn-Jones.

Some five years after this incident, when Major Elwyn Jones was a prosecutor at the Nuremberg war trials, he was shown Adolf Hitler’s signed orders for the invasion of Britain in August 1940. The first paragraph included the words ‘Although the British military situation is hopeless, they show not the least sign of being prepared to compromise.’

Polly was pregnant again, but still working. She wrote to Elwyn every day:

17 Sept ‘I’ve been in London all day today. A bomb hit the Langham Hotel so the BBC is a bit disorganised. However I did my piece all right…then to Middlesex Hospital where the doctor informed me that Daniel is all in the wrong position…there was a raid just before we were leaving and I went to the hospital basement and had a bit of a nap on the mattress there.’

18 Sept ‘The fourth siren today just sounded. Poor Poppet will get celery-coloured from living so much below ground level.

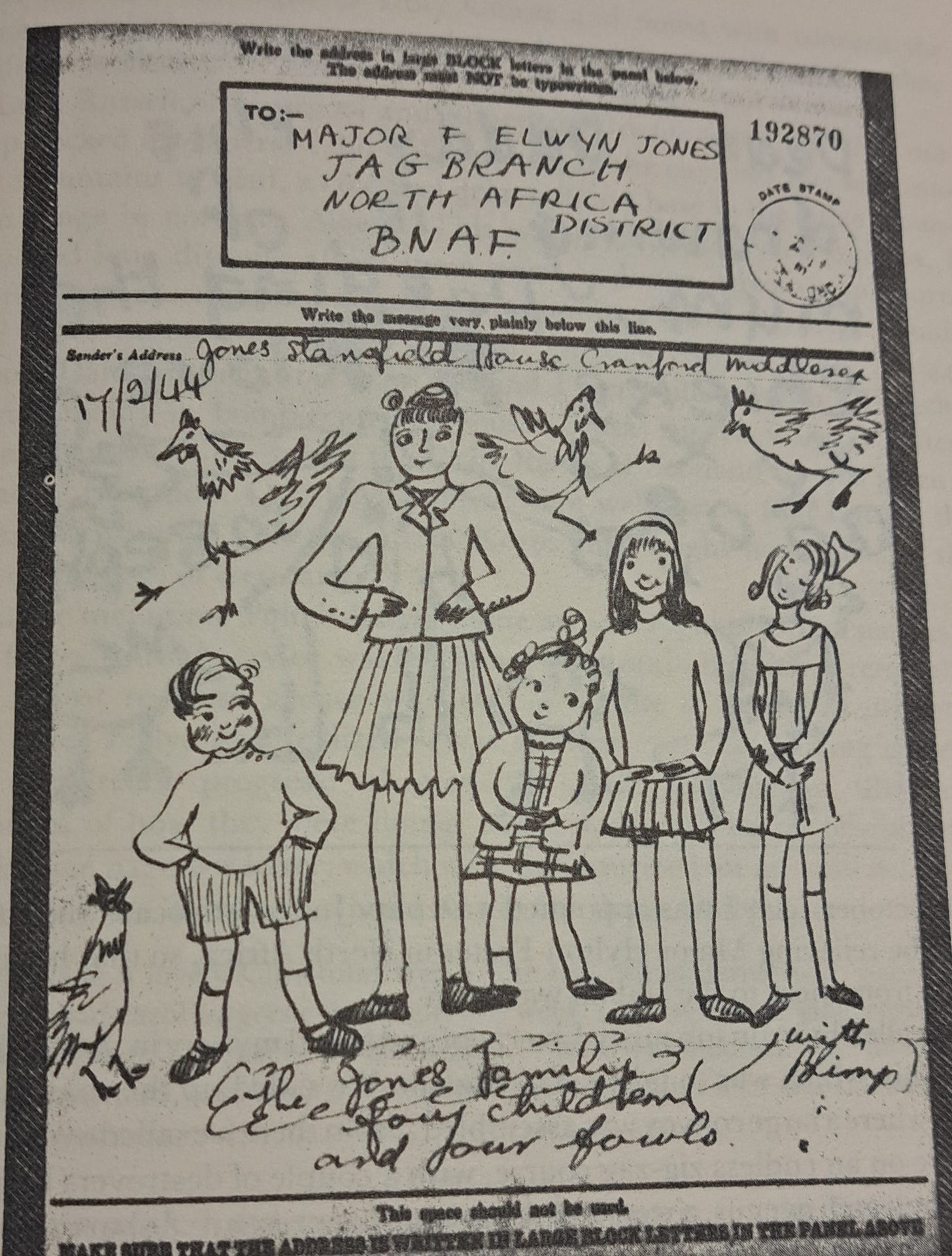

In 1941, Jones was appointed Staff Captain in the Department of Army Legal Services. By 1943 he was on his way to North Africa, sharing cabins with Peter Ustinov. Polly wrote that she had made a lovely Christmas tree in the hall, decorated with paper stars. ‘We’ve had carol singers every night this week, the children made gingerbread men in the kitchen…I waited for hours in a queue today for Christmas pork and beef.’ In February 1944 Polly was working for the Ministry of Information and had bought some hens. Her annual Valentine’s card message to Elwyn included a poem, the last verse of which read ‘Listen to the Joneses pray/Lay you devils, lay! lay! LAY!/On omelettes we hope to dine/So please to be our valentine.’

In June 1944 Elwyn was delighted to find that his name had been added to the list for candidate selection in Plaistow, a strong Labour seat, but also one of the worst blitzed areas of London, with nearly a thousand people dead and fourteen thousand houses destroyed. The spirit of the Blitz was alive and well, however: he was told the story of the old woman rescued from her completely destroyed house clutching an unopened bottle of whisky. When a fireman suggested that this might be a good time to open it, she replied ‘Not bloody likely, I’m keeping it for a real emergency.’

Elwyn Jones was elected in the Labour landslide, and would remain the MP for Plaistow and then West Ham until 1974, when he joined the Lords as Lord Chancellor. However he was absent for much of the first year, working as one of four junior Counsels for the Prosecution in Nuremberg. Polly continued to work as an author and artist, visiting Russia as a journalist in 1952. After a bad experience flying back from Germany at the end of the war, she tended to avoid planes, often joining Elwyn on his numerous legal trips abroad by cargo ship, where she filled her time blissfully in writing and drawing.

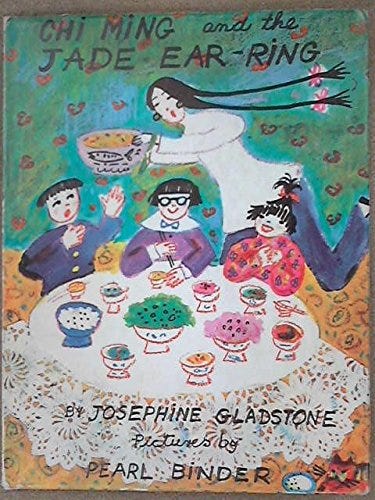

Elwyn Jones’ career as a barrister led to his appointment as Attorney General in the first Wilson Government of 1964, in which position he was Counsel to the Enquiry into the Aberfan Disaster, as well as Torrey Canyon(the oil tanker) and Ronan Point (the tower block). He was also chief prosecutor in the Moors Murder trial. The list of groundbreaking legislation passed under his aegis in the 1960s is too long for this Substack. Polly continued to write and to illustrate books, including the charming Chi Ming stories, written by her daughter Josephine and read on Jackanory by Judi Dench.

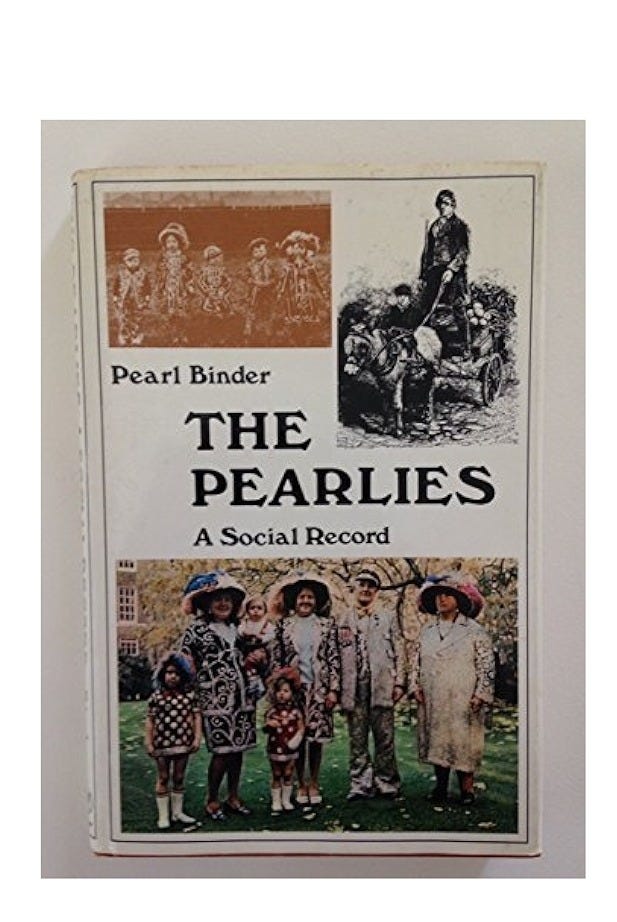

However, by the 1970s, much of Polly’s energies were consumed by a very unusual cause; the plight of the Pearly Kings and Queens. These colourful individuals are a traditional London philanthropic group of working-class men and women, known for their elaborate outfits decorated with mother-of-pearl buttons. They raise money for charities by holding events and appearing at public functions, a tradition that dates back to Victorian times and was formalized by Henry Croft in the late 1870s. By the 1970s there was a danger that the tradition would die out. To Polly with her passion for textiles, costumes, and the customs of the East End, this was clearly a cause worth pursuing, and she did so forcefully, using every trick at her fingertips, including writing about them:

and including them in public events. In 1976, Polly arranged for Rosie Springfield, Pearly Queen of Stoke Newington, to visit Washington to take part in the Bicentennial celebrations, where she entertained an audience with Cockney music hall songs.

I feel that this Substack has hardly begun to cover the extraordinary, energetic and purposeful lives pursued by Elwyn and Polly Jones, there is so much more to say, archives to explore, and I have only just started. But I wanted to share some of this with you. Here, to finish, is an extract from a letter Polly wrote to her husband in 1940 after he had finished twenty-four hours’ leave:

Yesterday was one of the happiest days for years, first waking up in bed with you, to find we were both alive and had had several precious hours of sleep into the bargain, then seeing my husband busily pottering blissfully about, sitting in his own armchair and picking his own apple trees and playing with his Poppet, then my rather successful dinner (even if the dumplings were a bit indigestful) and you buying me sugared almonds and fetching me home in the siren.

Such loving sentiments, such a happy couple in the midst of so much horror. A partnership that sustained them both, and made them both the stronger. Elwyn Jones’ career was extraordinary, but it is quite clear reading his memoir that his wife was throughout an inspiration and a joy.

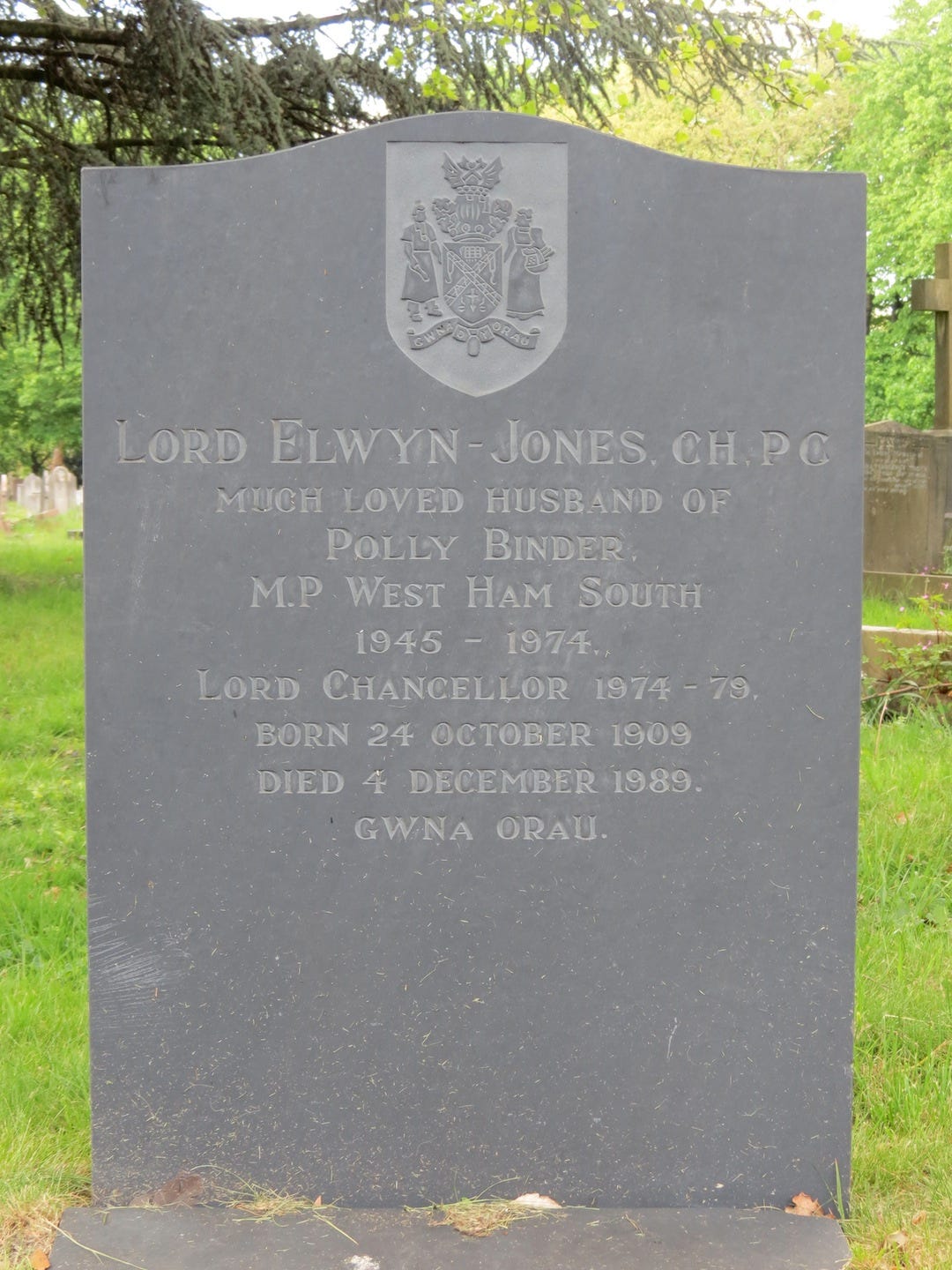

Elwyn Jones died on 4 December 1989, Polly died just seven weeks later. Elwyn is buried in the City of London Cemetery, in the heart of the East End they both cherished and served all their adult lives. his tombstone bears the Welsh phrase Gwna Orua - Do Your Best. A good motto to live by. Polly, who had become a Quaker in the 1950s, is buried in a Friends’ cemetery.

Sources: In My Life, by Lord Elwyn-Jones, and Comrades in Art: Artists Against Fascism 1933-1943 by Andy Friend

You're not going to believe this. Pearl Binder has just this minute been mentioned on a TV show my husband's watching called "The Footage Detectives" on Talking Pictures TV. They're showing BBC footage from the 30s and 40s. She was mentioned in an advert for the Radio Times. I just overheard it and nearly fell off my chair! 🫨

Two amazing stories in one. I can't imagine how much pressure Elwyn must have felt to succeed at Cambridge, given the sacrifice his family made to put him there. I'm sure you're right and reams could be written on both of them: he was at the centre of so many highly significant and tragic events! They must have been very devoted. I notice from his gravestone that he remembered his Welsh roots: the last line means "do your best" . Polly and Elwyn certainly did! Another fascinating read. Thanks, Sarah.