The Ministry of Enthusiasm

One Hundred and Twenty Years of the Workers' Educational Association

Canon Barnett, of Toynbee Hall, to whom one would naturally go with any projected scheme for the betterment of working-class conditions… said it would need a lot of money - £50,000 perhaps. Mrs Mansbridge produced a lower estimate. She thought it could be done, for a start, on two shillings and sixpence, and this she was prepared to contribute from the Mansbridge housekeeping account. Accordingly, on Mansbridge’s return from his discouraging encounter with Canon Barnett, an ‘Association to Promote the Higher Education of Working Men’ was duly constituted with an operating capital of two shillings and sixpence. Its name was longer than its membership, which consisted of Albert and Frances Mansbridge.

Mary Stocks, The WEA: The First Fifty Years

Schemes for the education of the ‘Working Man’ were not unusual. The Mechanics’ Institutes were founded in Scotland in the 1820s, encouraged and subsidised by employers, and were designed to improve the technical and scientific knowledge of the workforce. The London Mechanics Institute persists to this day, now known as Birkbeck College. Although many of these buildings also housed libraries, they tried to avoid subjects that might lead to discontent, such as history, politics or economics, or anything that would enable a working class man to challenge his betters. But, as FD Maurice and his disciples realised, this was never going to be enough to satisfy the curiosity of an increasingly literate population. The first Working Men’s College was opened by Maurice in London in 1854: it also still exists today as the WM College. It began to admit women in 1965, although there had been a College for Working Women in Victorian times, which survived as Frances Martin College, supported by Alexander Macmillan the publisher, until it merged with WM in the 1960s. Its curriculum was much broader.

In 1873, Cambridge University launched its ‘University Extension Lectures’, which relied on Cambridge tutors travelling the country lecturing - it was rapidly followed by a similar system from Oxford. However the classes were not free, and it soon became clear that they were most popular, highly popular in fact, with bored and under-educated middle class women who could afford the fee and the time. Nevertheless, the growing Co-operative Movement started to offer scholarships for its members to attend these lectures. And this is where Albert and Frances enter the story.

Albert Mansbridge was born in Gloucester in 1876, the son of a carpenter. The family moved to London and Albert won a scholarship to Battersea Grammar School, but the finances could not support him staying on past the age of fourteen and he found a job with the Cooperative Wholesale Society. Yet his intellectual curiosity had been piqued and he explored London as a source of education, history and culture, attending lectures whenever he could, joining libraries, visiting galleries. He worked as a Sunday School teacher, and, just like the Christian Socialists before him, became convinced that his fellow working classes needed to be better educated if they were going to participate in democracy and have any say in their own lives.

His vision was a society that would bring together the power of the trade unions, the co-operatives and the universities to launch classes around the country. Initially the plan was to provide lectures, along the lines of the Oxford and Cambridge Extension system, but within a very short space of time the idea of a more democratic tutorial-based class was developed and quickly took off. By 1905 Mansbridge was running the organisation as a full-time occupation, and by 1908 there were fifty branches. It was in Rochdale that the tutorial system was pioneered. It was agreed that if thirty men could be found who would commit to attend regularly, to submit written work for inspection, and to persist for a minimum of two years, then the WEA, as it was now called, would fund a tutor for that group. Almost at once, the workers of Longton in Staffordshire agreed to make the same commitment.

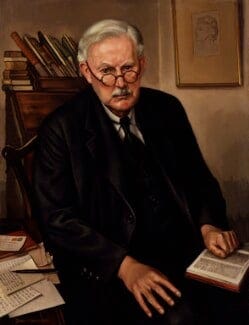

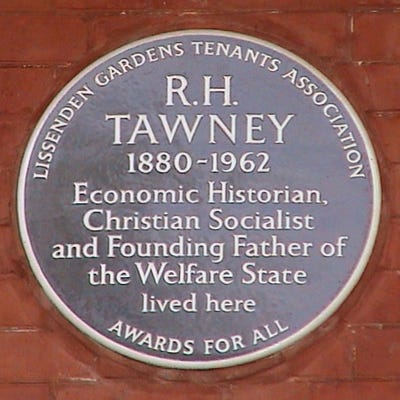

The man they found, by an extraordinary stroke of luck, was Richard Tawney, born in India in 1880, and educated at Rugby School and Balliol College, Oxford. Among his closest friends were William Temple, a future Archbishop of Canterbury, and William Beveridge, architect of the British welfare state. At the time of his appointment he was teaching economics at Glasgow University, but such was his enthusiasm for the project that he would leave Scotland by train on Friday to teach an evening class in Longton, travel to Rochdale for the Saturday class, and back to Glasgow. He was a deeply impressive, if unusual individual: one of his students would later write

Though he spoke with the accents of Balliol and carried his head like the monarch of the glen, he looked at times like a manual worker who had not bothered to tidy himself up for a collar-and-tie job. Any room inhabited by RH Tawney would in a short time present a scene of chaos amounting to squalor.

But how lucky were these students! This is the man who would become one of the most influential economic historians of the twentieth century, the author of Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, and The Acquisitive Society. Yet however much he taught his students, he always said that they had taught him more:

I can never be sufficiently grateful for the lessons learned from the adult students whom I was supposed to teach, but who in fact taught me. … Asked when I received the best part of my own education I should reply not at school or college but in the days when as a young, inexperienced and conceited teacher of tutorial classes I underwent week by week a series of friendly but effective deflations at the hands of the students composing them.

By 1909 there were thirty-nine tutorial classes operating, run by the fellows of universities including Oxford, Cambridge, London, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield. ‘The salaries meant little but the work meant much.’ The WEA impressed upon its tutors that it was less interested in what the classes were taught to think, as in ‘how to think.’ WEA branches were established in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and both Albert and Frances travelled the world, including the United States, lecturing and inspiring others on the subject of adult education.

In 1908 the WEA began to publish a magazine, Highway, which soon had a circulation of ten thousand. In 1909 it established a Women’s advisory Committee and began to offer early afternoon classes that women could attend before the children came home from school or their husbands were wanting their tea. It became clear that the students needed books: the Carnegie Foundation funded a central lending library in London. A major feature of the organisation, the summer school, was launched in 1910, initially held in Oxford. The first school featured a group of women-only students, paid for by female dons.

At the outbreak of WW1, the WEA could boast 2,555 affiliated organisations (ie local unions and co-ops). 179 branches, eleven thousand fee paying members, three thousand of whom were in tutorial classes, and many more students who only paid class fees, not membership subscriptions.

The years between the wars saw steady growth in numbers, although because the funding came partly from local education boards and central government, an increasingly vocal group of left wing academics, including those of the newly formed Labour College funded only by trade unions, attacked it as a ‘sell-out’. During the war, the WEA delivered classes to the forces. The impact it was having on the population can be seen in the intake of new Labour MPs into the House of Commons in 1945: according to the WEA’s own statistics, fourteen members of the Government, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Hugh Dalton) were tutors, former tutors, or members of the WEA Executive. Fifty-six active WEA tutors or students were MPs. George Tomlinson, Minister of Education from 1947, was a former student. Tawney claimed that by the late 1940s, one in three Labour MPs had WEA links. One of these was Michael Stewart, a future Foreign Secretary, who had met his wife Mary when they were both tutors at a WEA Summer school. Mary was a full-time WEA lecturer.

Over time, Albert Mansbridge, despite several bouts of terrible ill health, became a recognised expert on the subject of higher education and sat on several Royal Commissions and Committees. He died in 1952, Frances in 1958. They are commemorated in Gloucester Cathedral, among other places.

Richard Tawney died in 1962. He left his estate to fund the WEA.

The WEA flourishes today. As its website says:

Our mission is to bring adult education within reach of everyone who needs it. We continue to empower adults by bringing great teaching to local communities across England and Scotland, reaching tens of thousands of learners each year. This could be in a local venue near you, or online via your computer, tablet or phone. It’s the small class sizes and the highly tailored ways that we teach that makes the difference.

It means a lot to me, because in the 1960s, when I was a very little girl, I remember that my mother was a student, working her way through classes on English Literature while I was at school, and writing essays while I had my tea. My mum was very bright, a scholarship girl at a local grammar school in Essex, but she had left school at fifteen to get a job. She joined the civil service, and married my father who rose through the ranks to quite a senior position in the Ministry of Defence. Whether my mother was just bored, or whether she felt the need to equip herself for the socialising that came with my father’s job, she was the ideal WEA student. The phrase, the Ministry of Enthusiasm, was coined by one of the organisation’s earliest supporters and tutors, William Temple. It is very hard NOT to be enthusiastic about such a worthwhile cause with such an illustrious history.

Next week I will be starting the story of the Open University, the biggest adult education project of them all. If you have enjoyed this, please hit the heart button, and share it.

For more reading on the subject, I recommend my principal source, Mary Stock’s The Workers’ Educational Association: The First Fifty Years

![An adult education class, 1937 [WEA archives] An adult education class, 1937 [WEA archives]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BxcS!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc3553d77-e8c6-4117-a7da-395cf5731128_1024x766.jpeg)

Tawney's Religion and the Rise of Capitalism is still an excellent lively read. I remember one or two odd creaky perorations, which I suppose reflect the lecturing style of the era, but I found it accessible and informative and well-argued, especially on how economics came unmoored from any moral foundations. A remarkable man.

These pioneers of education for working people had a real sense of education in the round, that it should make us more enquiring, more public-spirited and democratic, not just more productive and wealthy. With the marketisation of higher education and now its crisis it is surely time to rediscover this...

I did my library post-grad at Manchester Metropolitan University and they liked to say that, because they started off as a Mechanics' Institute, they were older than the University of Manchester!

It's so interesting how the WEA courses spread and how huge the appetite was for them. Human beings love to learn!