Nelly and May: Parallel lives

How two women born in 1862 made careers in the Victorian art world

This week I had a special treat: a trip to one of my favourite local art galleries, the Russell-Cotes in Bournemouth, always a delight, but this time to marvel at the beauty which is the May Morris: Art and Advocacy Exhibition.

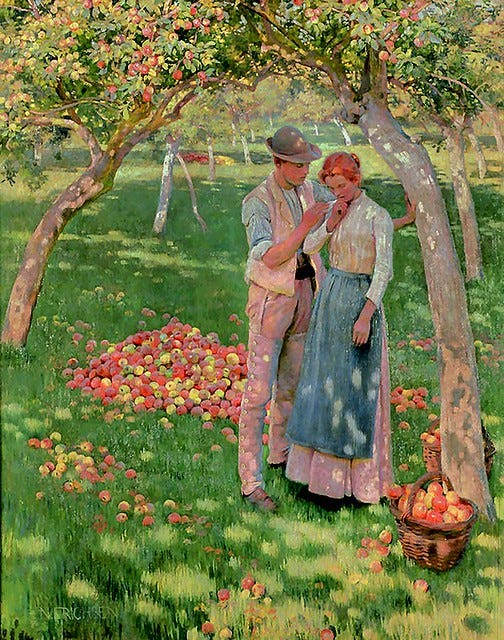

This is not the first time I have come across May, the daughter of William Morris, and her extraordinary, beautiful embroidery. Back in 2018, Court Barn in Chipping Camden, another jewel of a local museum, staged an exhibition entitled Women in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which featured May Morris, Louise Powell (a pottery designer who worked for Wedgwood), and the artist Nelly Erichsen, the subject of my biography, published the same year.

What was particularly interesting, and new to me, in this latest exhibition, is the focus on May Morris as a businesswoman, an entrepreneur. Recently I’ve been enjoying

’s Substack, Women Who Mean Business: and here is the perfect example of a Victorian woman who took her art seriously, but who also worked to create the opportunity for other female embroiderers to earn a living. Her contemporary Nelly Erichsen never went into business, but she trained over several years to be come a professional artist, and tried to be self-sufficient, self-supporting, throughout her adult life, albeit not always very successfully. These two women were trailblazers for the professional caste of the twentieth century; middle class educated women no longer needed to be confined to the house as wives, governesses, or maiden aunts, they could have careers of their own.Nelly Erichsen and May Morris have much in common, not least that they were both born in 1862. They both came from relatively comfortable middle class families: the Erichsens were a Danish family who from 1870 onwards lived in Tooting, South London. Hermann Erichsen was a company director in the burgeoning telegraph industry.

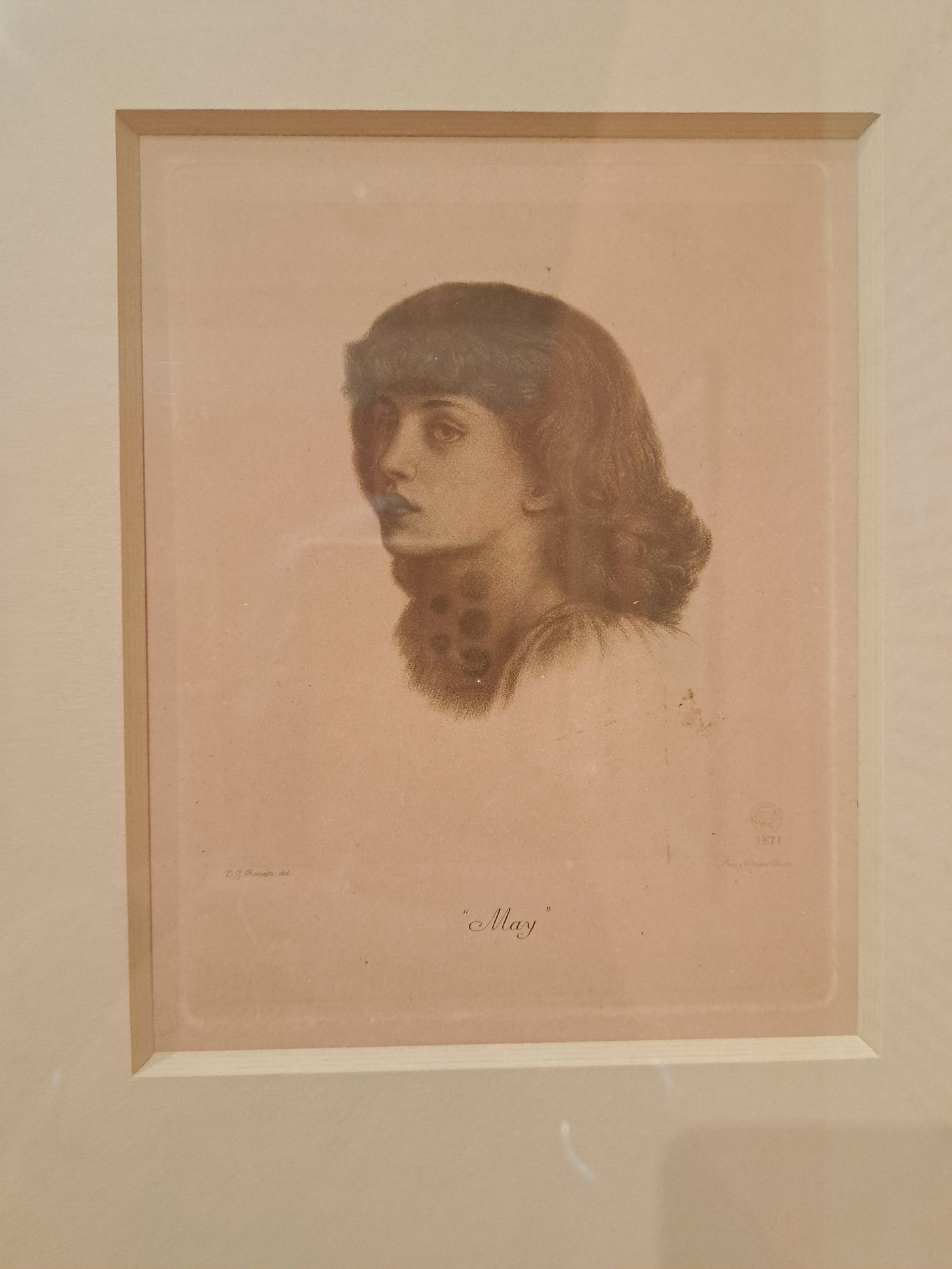

William Morris, May’s father, also came from a wealthy family, his father having made money in the City. However the two girls had very different childhoods: Nelly was one of six children, home-educated in a stable, suburban environment. May’s childhood was more chaotic. Living with a father of the ferocious talent and energy of William Morris would never have been peaceful, and William had rejected the life of leisure his father’s wealth could have provided, choosing instead to launch himself into the world of trade as the founder of Morris & Co, creating new trends in furniture and interior design. The family also became increasingly unconventional as Jane Morris’ relationship with her husband’s friend, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, deepened into a serious love affair.

The two crucial blessings that Nelly and May shared were exceptional artistic talent, and supportive parents. May was sent to the National Art Training School at the age of sixteen, to improve her practical skills in textile design and creation; Nelly won a place to study painting at the Royal Academy in 1880, one of the first women to receive her training at this prestigious school. These were young women whose parents took them seriously.

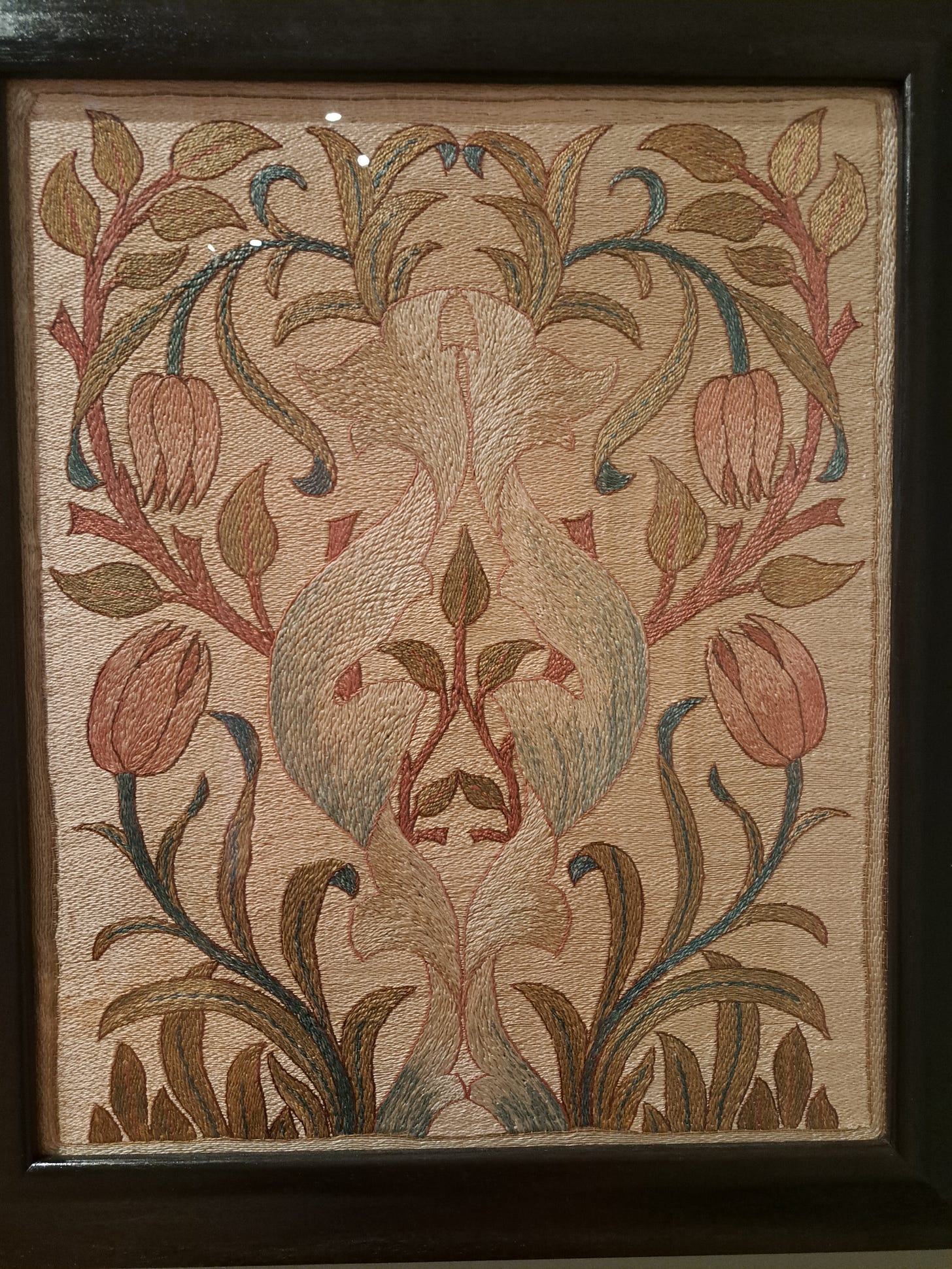

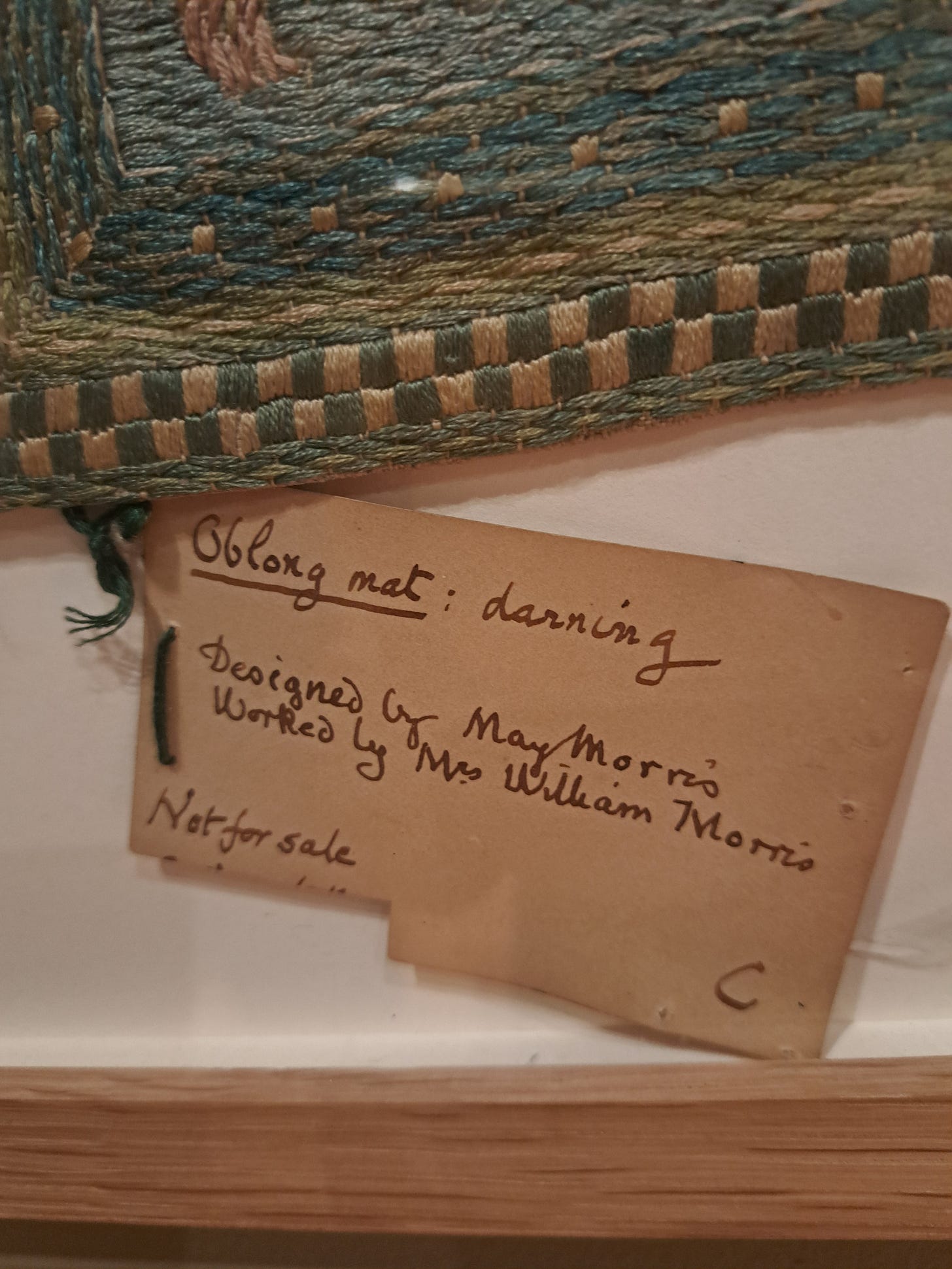

By 1885, at the age of 23, May had joined her father’s firm, taking on the management of of the embroidery department at Morris & Co. She led this team for more than ten years, until William’s death in 1896. During that time she expanded the number of women embroiderers to meet the growing demand for the firm’s beautiful fabrics, which she designed and worked on herself. According to the excellent notes at Russell-Cotes, she was responsible not just for the artistic leadership of the team, but for recruitment and training, for client liaison, and for sales and pricing. Staff were well paid, worked reasonable hours (ten til six, and a half day on Saturday), and were entitled to increments as their skills increased. A particularly profitable line that May developed was the sale of embroidery kits: these consisted of fabric pre-printed with a Morris design, together with instructions and a small worked section to illustrate the techniques involved. The firm’s embroidery was recognisable not just for the distinctive William Morris design, but for the richness of the silks and the subtlety of the colours at a time when the most usual form of the handicraft comprised stiff, regimented woollen tapestry.

Nelly Erichsen was also determined to make a living from her artistic talents, but despite her success as a painter in oils, with many of her works winning space at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, she could not survive on the money it brought.

She could earn a little by taking commissions to paint family portraits, and along the way developed particular skills in the use of pastels.

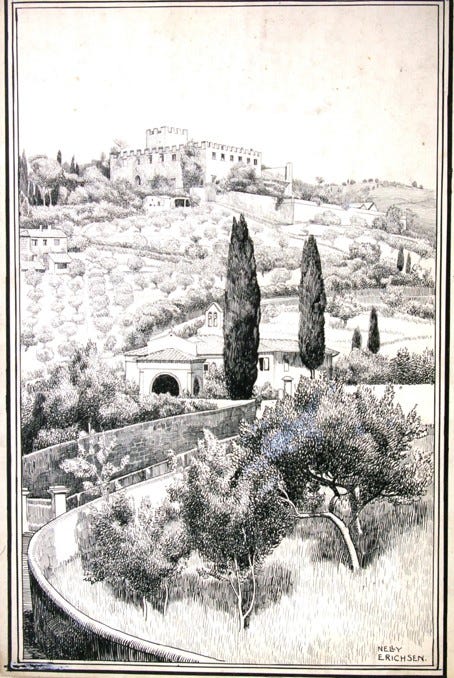

Then in the 1890s Nelly turned from canvas to drawings, and for the rest of her life, until the Spanish flu took her in 1918, she worked for publishers such as Macmillan and Dent as an accomplished illustrator, mostly of travel books in Italy and England.

There were interests beyond art that Nelly and May shared, and I am constantly frustrated that I cannot find evidence that they knew each other or even met. Both women moved in the same Fabian/socialist circles of fashionable and artistic London in the 1880s and 1890s. I know, for instance, that they had friends in common: Nelly had a friendship with George Bernard Shaw; May had an affair with him, one which created difficulties in the brief period when she was married to another man, the socialist Henry Halliday Sparling. Although in his diaries Shaw considered this ménage a trois as ‘probably the happiest passage in our three lives’, Sparling seems to have been less convinced - he left May and eventually they divorced. Shaw married someone else. Both women were also supporters of the suffrage movement. And both women were linked to the Arts and Crafts movement, May inevitably so, following in her father’s footsteps. Nelly’s involvement came later in her life, when in 1908 she moved to Chipping Camden, home of Charles Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft. May Morris herself founded the Women’s Guild of Arts in 1907, an organisation offering support and camaraderie to women craft workers such as herself.

May Morris’s life after the death of her father was sufficiently busy and interesting to give the lie to any suggestion that she was riding on his coat tails. In 1897 she became a visiting tutor at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, and from 1899-1905 was head of the Embroidery Department, as well as a lecturer in colleges and schools across England. She learnt silversmithing and became an accomplished jeweller. In 1909-10 she went on a lecture tour of North America. Finally she devoted the end of her life to burnishing her father’s reputation, at the expense of her own, editing no less than twenty-four volumes of his writings. She died at Kelmscott, the Morris family home in Oxfordshire, in 1938.

May Morris’s reputation is constantly growing, partly on the back of the worldwide interest in William Morris and his work, but justifiably in terms of the undoubted skills she possessed and the single-minded determination with which she pursued her art. Nelly Erichsen sank into utter obscurity after her death in November 1918 in Tuscany - it was a chance find of some of her line drawings in a publisher’s auction twenty-five years ago that led to my family’s interest in her work. This is by no means unusual, many learned articles have been written about why, historically, women artists seem to disappear from the record. The Russell-Cotes exhibition is a perfect illustration of how much pleasure can be gained from the study of these talented, and often overlooked, women artists. If you have a spare day this summer and find yourself anywhere near Bournemouth, I would encourage you to visit, you won’t be disappointed.

Now, who would like to stage another Nelly Erichsen exhibition?!

If you want to know more about Nelly, here are some links to follow, and of course I would encourage you to buy the book!

Two terrific women. I know about May Morris's work but Had never heard of Nelly. A new search starts!

Absolutely wonderful. Thank you, Sarah!