I have a confession to make. I have struggled with Substack this week - or at least, I went down a rabbit hole too deep to inflict on any of you. I have noticed that the posts which get the greatest response are the ones about the women who Macmillan published: Anne Gilchrist, Mrs Oliphant, Janet Ross, and Mrs Craik. So I thought I should focus on perhaps his most prolific contributor, Charlotte Yonge (I’m pretty sure you pronounce her surname ‘Young’ but I’m happy to be corrected.) She was already famous when in 1864 she approached Macmillan to take her on: as a very young woman she had had massive success with The Daisy Chain, and The Heir of Redclyffe was apparently the most popular novel among the officers in hospital during the Crimean War. She is little read today - I have just ploughed through The Clever Woman of the Family, as it was such an appealing title, and it really shows how dedicated I am to the cause…I don’t think any of her work is in print today, although Virago give her a shot in the 1980s. It wasn’t bad, but, compared with say Mrs Oliphant’s Hester, it isn’t ageing well.

I thought that I would focus on a particular episode in her relationship with Alexander Macmillan: her involvement in the popular Sunday Library Series, published between 1868-71, which included popular volumes by Charles Kingsley and Tom Hughes, as well as more worthy tomes, two by Yonge herself. The aspect which had caught my attention was the difficulty Alexander had in keeping the peace between the High Church, Tractarian Miss Yonge, and the free-thinking educationalist, Frances Martin, whom he asked to edit the series. Macmillan was, like Frances Martin, a follower of FD Maurice (see my piece https://harkness.substack.com/p/what-is-the-point-of-fd-maurice) and was therefore in favour of religious toleration and free speech. But Miss Yonge pushed Martin to the limit and….

You see, it’s quite a deep rabbit hole, and I don’t think you need to follow me down it! Maybe Frances Martin will get a post of her own, after all, the Frances Martin College for Working Women in London survived under her name until 1966. Do shout if you would like to know more!

So I’m not going to write about these two impressive women today, but for those of you who haven’t yet read my biography of Nelly Erichsen, I thought I would digress a little and explain how this passion for rabbit holes all started, in Tuscany.

Bagni di Lucca is not the most glamorous town in Tuscany. For a start, it is well off the beaten track, nearly an hour’s drive north of Lucca. For Italy’s Victorian visitors, drawn initially to the romance and history of Florence, Bagni was a picturesque destination for picnic outings – a well-known spot for literary pilgrims wishing to follow in the footsteps of the Brownings. The cooler climate was a welcome relief from the heat of the valleys. Perhaps it was also a refuge from the hurly burly, gossipy life of the Anglo-American community that dominated Florence. There was a spa, but it is hard to imagine that the climate of these dank, misty valleys actually did the visitors any good at all, and many now lie in the well-stocked English graveyard, across the river on the edge of the town.

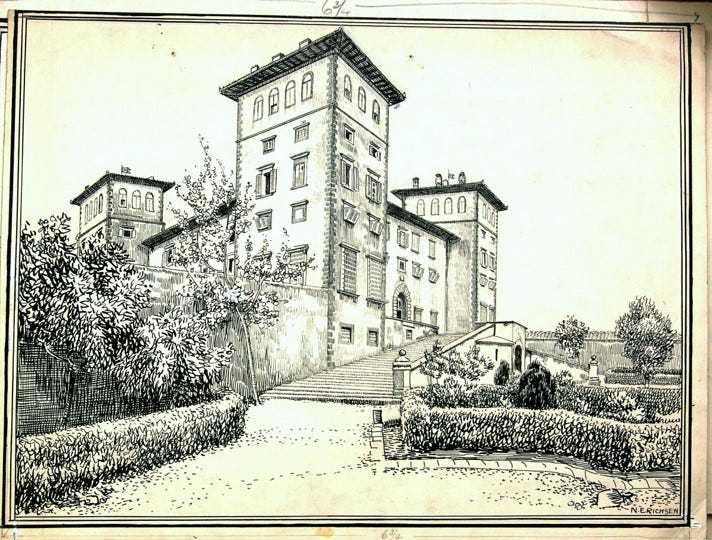

One very wet October morning, twenty years ago, three damp, disheartened but otherwise healthy English travellers peered wistfully through the rusty iron gate of that same graveyard. In a plastic envelope we carried a rather damp photocopied map of the town, a tourist leaflet in laughably poor translation and some scribbled notes: all clues to three forgotten lives. The quest had started two years earlier, with the chance find in a London auction house of a dusty wallet containing a portfolio of original book illustrations dating from the 19th century – extraordinarily detailed and rather beautiful line drawings of stunning Florentine villas.

After months of sporadic research the trail to find the artist had led to Bagni - it seemed unfair that having come this far, the cemetery gates should be locked. No-one in the town seemed to know who had the key. In no time at all we would have to leave to catch our plane home. In so many ways, this frustration was a metaphor for the entire project – we could catch a glimpse of our woman through the railings, but it was very unlikely we would ever actually find her.

My husband, my eldest daughter and I had arrived late the evening before after a much longer drive than expected, along roads which had looked temptingly picturesque, straightforward on the map, but were actually hair-raising. An hour or so was spent poking round the town in miserable, drizzly conditions. We found a few traces of our quarry – a street named Via Evangeline Whipple; a house that may once have been Casa Bernardini, our artist’s last known address; and an Anglican church now only used to store a dusty cobweb collection of books left behind by long departed English residents. It was too dark to do more. We consoled ourselves with spaghetti and hot chocolate, the best comfort food. Overnight, as we struggled to sleep in the scruffy pensione, the rain began in earnest. When we crossed the Lima the next morning by the old footbridge towards the cemetery, the river had doubled in size, changed colour to a murky threatening brown, and bore in its wake the debris of a terrible night on the mountainside. This felt like a hopeless waste of time.

The gate was firmly bolted and the rust on the lock suggested that no-one expected visitors. Determined to teach to my eleven year old daughter a lesson in resilience, I scrambled over the wall at the back, at least one of us should try to find our quarry. But Italy being Italy, just as I was fighting my way through the sodden nettles, help did arrive, in the shape of a fussing, elderly woman in a headscarf waving a huge iron key, talking nineteen to the dozen under her breath in Italian, and hurrying Peter and Harriet through the gates. I tried to look nonchalant, avoiding her eye, avoiding the question of why I was already inside.

The graveyard had been laid out nearly two hundred years earlier, and was now particularly dilapidated – a muddle of overgrown, broken and almost illegible tombstones – the lichen-encrusted inscriptions telling tales of military men, sons lost at sea, faithful wives and lonely spinsters. Wordsworth’s daughter-in-law Isabella was buried here in 1848, a long way from her Cumbrian home. In one corner loomed a truly bleak memorial to a very wretched woman, the writer known as Ouida, once the toast of literary London and Florence. Her gravestone had been funded by an anonymous donor. It seems that by the time she died, quite possibly of malnutrition, certainly lonely and impoverished, no-one even wanted to admit to being her admirer or friend. And then, right at the back of the graveyard, in a private plot surrounded by railings, we finally spotted the resting place of the women whose story we had come to pursue.

Nelly’s surname was misspelt, a not uncommon issue we had faced when trying to track her down but particularly sad to find it preserved like that on her tombstone.

Three remarkable lives. One burial plot. These women made up a formidable trio; each had been a pioneer in their own way. Evangeline (‘Eve’) was an attractive and wealthy widow when she married an elderly bishop renowned for his missionary work with the Sioux in the era of the Native American Wars. Rose had served as First Lady of America when her bachelor brother was elected 22nd President of the USA, an unwanted interruption to her career as a writer and educationalist. Rose and Evangeline first met in the winter of 1889-90, but separated when Eve married her bishop. After his death, they were reunited and finally left America to live together in 1910 – theirs was a passionate and loving relationship, which had to be lived well beyond the glare of public curiosity.

And Nelly, who had led us to the place of their self-imposed exile, was one of the first women to challenge the male dominance of both fine art and commercial art in Britain, and to make a living from it. The youngest of the three, with the simplest gravestone, she was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the daughter of a wealthy professional Danish family. After studying at London’s Royal Academy in the 1880s, she had carved out a moderately successful career for herself as a painter, book-illustrator, translator and writer. She worked with the giants of the Victorian publishing world, Alexander Macmillan and JM Dent, and jointly published travel and architectural guides with authors such as Janet Ross and Edward Hutton. She was the one that we had primarily come to find, driven by curiosity about the life of an artist whose work we had come to love.

From 1912 until November 1918, these three extraordinary independent women shared a house together in the quiet backwater of Bagni di Lucca. But as the gravestones tell, in 1918, tragedy struck, when both Rose and Nelly fell victim to the Spanish influenza epidemic which decimated post-war Europe.

So much of their story was remarkable – not just how two well-known and highly respected American women in their later lives defied convention to make a home together, and how all three women worked to serve their adopted countryfolk and advance the allied cause in war-torn Italy, but also what their history tells us about how, one hundred years ago, life was changing so completely for women of all classes. The growing possibilities for financial independence began to open up real choices for women in lifestyle and profession.

Nelly Erichsen was born exactly 100 years before I was, in the first half of the reign of Queen Victoria, when women’s rights were few and far between. She lived through an explosion of change for women across the western world – sweeping across the spectrum of education, politics, property rights and sexual behaviour. By the time she died, women had won the right to vote in British parliamentary elections. Sadly she left no diaries, few of her letters have survived, and no-one has catalogued her considerable portfolio of paintings and drawings. She never marched with the suffragettes or chained herself to railings. She was a dutiful daughter and a doting maiden aunt, travelling between and lodging with relatives and acquaintances, living out of suitcases, more as a companion than a friend, and not always welcome. If she had a lover, male or female, the relationship left no trace. We can document certain places and dates in her life, but what brought her to those places, and how she felt about her life, can only be assumed. We see her life only in outline, with none of the detail that she put into any of her beautiful drawings or paintings.

An exact contemporary of Nelly, Mary Kingsley, the explorer and writer, was to say of herself ‘My life can be written in a very few lines…it arises from my having no personal individuality of my own whatsoever. I have always lived in the lives of other people, whose work was heavy for them…it never occurs to me that I have any right to do anything more than now and then sit and warm myself at the fire of real human beings.’ And yet today Kingsley is seen as a pioneer whose brave and often solitary work helped to transform European perceptions of African culture.

It was hard for women such as Mary and Nelly to reject the expectations and shackles that Victorian society placed on them, but each in their own way managed to do just that. We owe it to them to tell their stories and to celebrate their achievements even though they were rarely if ever encouraged to do so for themselves. And where we lack the raw material, we have to use our own experiences, our own understanding of what it is like to be a woman trying to make it in a male-dominated world, to fill in the gaps. I never expected to write a book, but Nelly’s story captivated me and seemed to demand to be put on paper. At times it felt like an impossible task, I peered through railings and climbed over walls trying to find her, but she was elusive. But I did not give up because the coincidences and parallels kept striking me. At one point, towards the end of her life, she wrote to a publisher that she was trying to reclaim and collect in one place her scattered possessions and artistic creations, something that a life lived out of a suitcase had previously made it hard to do. She never succeeded, as events, war and then death overtook her and her possessions remain scattered. Many have been lost, but enough have been saved, even treasured, by family members who loved her, for me to begin to piece her life together.

For those of us women who take a career and financial independence for granted, Nelly deserves our admiration and respect, for she pioneered the path we now all follow – not by protesting, fighting or shouting, but by quiet professional determination. Her life deserves notice for that alone. But there is more: the communities in which Nelly lived, and the circles in which she moved, were fascinating. Something about her – her talent with a brush and pencil, her love of European and classical literature, her capacity for hard work and her will to succeed, marked her out for notice by better known members of late Victorian intellectual society. As a girl of 18, she was enrolled into the Royal Academy Schools on the recommendation of John Sparkes, later headmaster of The National Art Training School in South Kensington. She developed close friendships, which seem to have gone beyond family acquaintance, with the Macmillan publishing family. In the 1890s she spent time with George Bernard Shaw and his circle; in Italy she often stayed and collaborated with Janet Ross, doyenne of Anglo-Florence society, and through her she met the famous art collector Bernard Berenson. Shortly before she went to live in Italy for good, she spent time in the heart of the Cotswolds, near where I now live, at Chipping Campden, as an associate of CR Ashbee’s Arts and Handicrafts Guild, and for the last six years of her life she lived and worked with two other women, born on a different continent but living similarly independent, bluestocking lives. In her own quiet way, Nelly’s story illustrates a new way of living for independent middle class females – she was single, self-financing (though not without worry, ill-health and struggle), and seems to have found fulfillment only in her work. Ultimately she died helping others – one of the many millions who succumbed to the Spanish influenza epidemic which wreaked such havoc worldwide in the aftermath of the Great War. Her death resulted from her decision to devote herself, in her late fifties, to the refugees displaced by an unimportant campaign in Italy, the country she so loved and had chosen to live in. Working with refugees seems worthy and brave even in the twenty-first century, but a hundred years ago it must have been daunting in the extreme.

Who she knew, where she travelled and what she achieved as a self-supporting professional woman in the dying years of the nineteenth century, made her life a window through which I realised I could examine more than three decades of English Victorian and Edwardian intellectual and artistic life. More importantly, the route she took and the struggles she faced to support herself, made her an unsung pioneer for women’s experience during the twentieth century. Her life sparked my imagination, and led me on a journey I never expected to take, both actually and metaphorically. And that is why I told her story.

Nelly Erichsen: A Hidden Life, published by Encanta Publishing

www.encantapublishing.com

Hi Sarah, your book has just arrived with a lovely hand written note inside. Many thanks & I look forwforward to reading it. ❤️

The thorough & deep research that you always do into such fascinating & often overlooked or forgotten people always amazes me! I’ve just ordered your book on Nelly Erichsen & look forward to furthering my education. Thank you 🙏