First of all, thank you to all my recent new subscribers, I’m delighted to see you here! For those of you who haven’t followed me from the beginning, I initially started this Substack just under two years ago because my manuscript of Literature for the People was finally with the publishers, and I had itchy fingers, I missed the daily reason to hunker down in my office in front of my laptop. At first I saw it as a means to fill in some gaps in the story of the Macmillan brothers, to flesh out some of the wonderful characters I had met in my researches, and of course hopefully to drum up some interest from people who might actually want to buy the thing!

The book finally saw the light of day in May last year, and although it never set the bestseller lists alight I have had some lovely feedback, some great reviews in proper journals like the TLS and the Literary Review, and it even got longlisted for an award. So it has been a very happy time. This month sees the launch of the paperback, and fittingly I will be at the Cambridge University Press Bookshop at 1 Trinity Street Cambridge on that very day, the 20th, to celebrate. After all, that is where the Macmillans’ publishing business really took off.

Tickets are still available! But most of all I would love you to consider buying my book. It’s nice to see it slowly move the dial on the Amazon bestseller charts: obviously it’s not in any of the big, important lists, and for some reason Amazon has decided to list it in History of Books (fine) and Living with Cancer…which is distinctly weird, and it’s not making much headway there. No, no-one knows why.

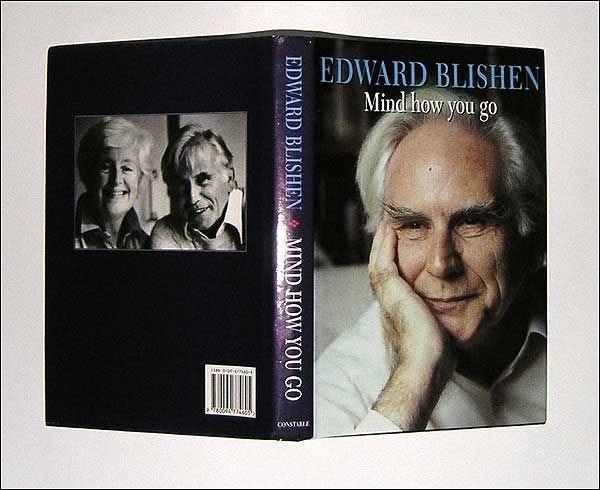

Meanwhile, this week I want to write about two lovely memoirs which have made me smile, and sometimes squeak with laughter. Both the writers are well-known authors of non-fiction, Antonia Fraser as a biographer and historian, still going strong, and Edward Blishen, famous for children’s books, for broadcasting, and for a series of autobiographical memoirs.

I recognised the name Edward Blishen (1920-96) from anthologies of children’s literature, which became his speciality. I have since discovered that having been a conscientious objector during World War Two he trained as a teacher and taught at a ‘challenging’ boys’ secondary modern school in North London. The book that he wrote about his experiences, Roaring Boys, was so successful that by 1959 he was able to quit teaching and become a full-time author. He was the editor for many years of the Junior Pears Encyclopaedia, I think my book looked like this? There were very few educationally-ambitious families in the 1970s who didn’t possess a copy.

And in the last years of his life Edward was a presenter of A Good Read, one of my favourite Radio 4 programmes that continues to this day. He is also well known for a children’s book, The God Beneath The Sea, written jointly with Leon Garfield. The memoir of his that I picked up was one of a series of autobiographical pieces. Lizzie Pye was published in 1982: the Lizzie in the title is his Mum. The book opens immediately after the death of his father, which leaves a rather startled Lizzie on her own, and ends with her death. In between Blishen weaves tales of his early married life when he and his wife Kate were sharing a large and very decrepit old house in Barnet with two other couples, and trying to do it up. Meanwhile Blishen was struggling with his day job, while he spent his evenings trying to become a writer, and failing to help Kate with two small boys. It is beautifully written, sometimes very funny, often very touching. Here he is writing about his newly-widowed mother:

It was two days after his death. She’d loved him amazingly, and found him amazingly abominable; and being with her during those two days had been like being present at the fall of an unpopular government. Part of my mother was out on the streets, shouting raucously and waving revolutionary flags. Part was grieved beyond words. She was toppling statues and releasing political prisoners, and had never known such hopefulness and such agony.

Blishen had written a previous volume about his father, which I have yet to read but I’m sure will be equally touching, funny and honest. His writing reminds me of

but seventy years previous. I will leave you with one more precious paragraph, that rang very true to me. His young son Tom has started school, and inspired by watching his father’s work, has become a keen story-writer:Spotting his approach with a thick notebook, I’d look round for an escape route…his stories were made out of narrative clichés laid lovingly end to end. He’d say ‘I’ve written a story. Its called The Adventure of the Boastful Hedgehog. Shall I read it?’ There was no despicable pretence of waiting for an answer, as with adult writers in similar circumstances. He’d begin at once…. Kate said it served me right. I was always approaching her with some equivalent of a thick notebook and confessing that I’d been…writing, as if it had been some disgusting activity quite out of character…

A dozen years younger comes Antonia Fraser, with a memoir of her early years.

This is a fantastic book, well worth a read if you, like me, find yourself fascinated by the British class structure, by shooting parties and balls and castles in Ireland and debutantes, but also, and this is why I picked it up, by the personalities of the mid-century Labour Party. Oh, and there’s a decent chapter on what it was like being at Oxford in the 1950s. Antonia was the eldest child of Frank Pakenham, better known to the British public as the eccentric campaigner Lord Longford, ‘famed for championing social outcasts and unpopular causes’, as Wikipedia puts it. Her mother Elizabeth Longford was also a successful and distinguished biographer, having spent many years campaigning to be elected as a Labour MP (while producing eight children). The family is ridiculously well-connected, descended from Anglo-Irish nobility as well as from the Chamberlains, and Harriet Harman is Lady Antonia’s cousin. Her first husband, Hugh Fraser, was a Tory MP: her second husband was the playwright Harold Pinter.

The memoir ends with Antonia’s marriage to Fraser, but there is a fascinating epilogue in which she charts her career as a biographer, starting with a competition with her beloved mother for the right to Mary, Queen of Scots as a subject. Her childhood seems to have been particularly happy, her teenage rebellions very slight, and her career post-Oxford illuminated by her stunning beauty but crucially by her passion for historical research combined with an enviable fluent writing style.

I have never been a fan of ‘misery memoirs.’ Of course we need to remember that not every childhood is happy, and that many people succeed in later life despite the most appalling handicaps and cruelties. But when the world seems a rather dark and worrying place, as it does to me at present, I turn to books for comfort, and both Blishen and Fraser made me happy. There are so many paragraphs I could give you from Fraser’s work, it is hard to choose just one or two. She comes across as perfectly happy to laugh at herself, blushingly modest and surprised at her own achievements. Here she is, failing to get the expected First at Oxford:

I went back to LMH and into the coin box by the porter’s lodge. I rang my father.

‘Dada, I’m awfully sorry but I haven’t got a First.’ Frank did not even pause. Quick as a flash he said: ‘Oh, I’m so glad. Because if you had, you would never have got married.’

About ten years later, I remembered the exchange and out of curiosity asked Hugh whether he would have married me if I had got a First.

‘Oh, but I always thought you did get a First.’ he replied.

The Antonia Fraser memoir sounds lovely - I love it when a biographer turns a light on themselves! Although now that I say that, Claire Tomalin is the only one I'm thinking of...

I love the sound of Antonia Fraser's memoir and that closing excerpt is wonderful! Edward Blishen's name is very familiar as a children's author, so I was glad to hear about his books for adults. The sort of thing that readers of Slightly Foxed magazine would appreciate, I bet.