‘There were two springs which bubbled side by side

As if they had been made that they might be Companions for each other’

William Wordsworth, ‘The Brothers’

In November 1844, the Poet Laureate William Wordsworth was staying in Cambridge, a guest of William Whewell, the Master of Trinity College. Whewell was a towering intellect in Cambridge, the wordsmith who coined the term ‘scientist’, a polymath, philosopher and theologian. Importantly, he was already well-acquainted with Daniel and Alexander Macmillan, the young Scottish brothers who had recently taken a small bookshop at 17 Trinity Street, Cambridge. Much of the money for this brave endeavour had been lent to them by Archdeacon Julius Hare of Lewes in Sussex, who had met Daniel for the first time the year before and been impressed by his earnest desire to use literature as a means of educating the working poor and bringing them back to the Christian faith. Hare was keen for the shop to succeed and, to further his investment, had introduced some old Cambridge friends as customers. Daniel wrote gratefully to his sponsor : ‘I had the honour of a visit from Mr Stanley [Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, later Dean of Westminster] and from Mr Monckton Milnes [poet and politician, Lord Houghton] , for which I feel indebted to you.’

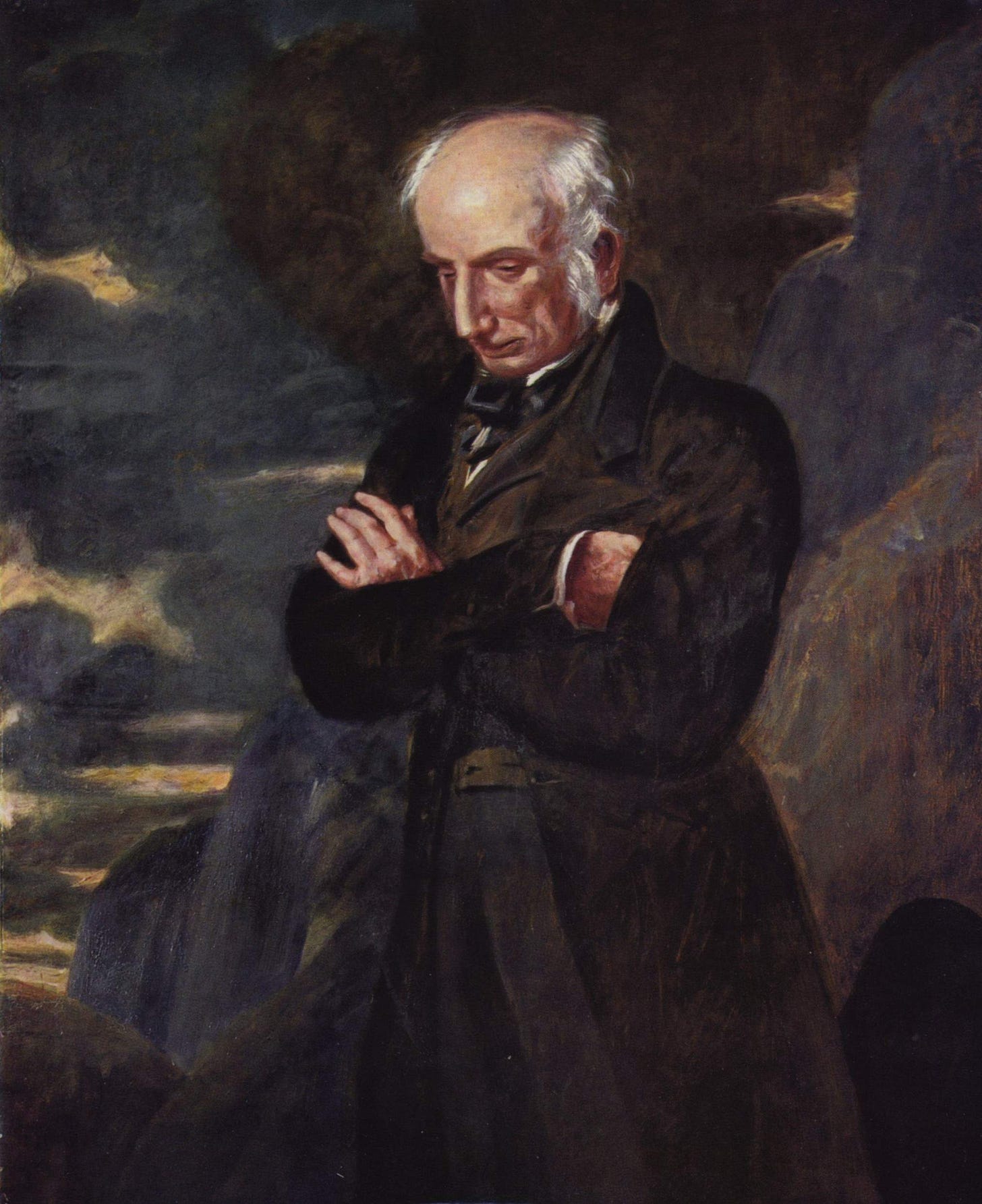

Then came the greatest coup of all, which must have filled the two young Scots with pride and wonder: ‘I had a visit from the poet Wordsworth. The Master of Trinity, Whewell, called and introduced him to me. He came upstairs and stayed with me an hour and a half and discoursed with the greatest simplicity on all manner of subjects. He called again in the afternoon …and stayed half an hour. This I counted a great honour.’ Wordsworth was seventy-four, and would have looked remarkable as he strode the streets of Cambridge. He had taken to wearing green shades to protect his fading eyesight, and Harriet Martineau, visiting him that same year in the Lake District, described him walking the country lanes ‘in his cloak, his scotch bonnet and green goggles’.

Many years later, Alexander Macmillan would still remember this visit, although in his memory the incident had lasted longer - he wrote to Sir John Coleridge: ‘One night my brother and I had him all to ourselves for some two or three hours. Perhaps partly in consideration that he had two somewhat enthusiastic young Scotchmen before him, he dwelt much on the influence of Scottish moral and spiritual mood on his own earliest thought and feeling; and as I understand him, claimed in the Pedlar to have realised the spiritual aspect of Scottish life in a way that none of her own bards had ever done or even adequately attempted. I remember his saying that all the Humanities in Scotch life, its war, its love, its hate, romance, humour, have been sung as perhaps no nation had ever sung them before, but that its spiritual life had never been in the least adequately done.’

The fact that Whewell took Wordsworth to meet these two young men in their little shop, the fact that Wordsworth enjoyed meeting them so much that he went back later alone to continue the conversation, is indicative of what would drive their success as booksellers and later as publishers: they were immensely likeable and interesting people to talk to. It meant nothing that Daniel had left school in Irvine, Ayrshire aged ten, and Alexander only fifteen - they could more than hold their own in a bustling University town. They were the very definition of auto-didacts, determined to master every book and periodical in the shop if necessary, to be able to share their passion and excitement for literature with their customers.

A year after Wordsworth’s visit, which would have proved a great talking point among the Cambridge undergraduate crowd, the Macmillans scaled up their business significantly, taking over the shop at 1 Trinity Street, still the site of the Cambridge University Press to this day. As Charles Morgan wrote in a history of the firm, published in 1943:

The old principle of unity between bookselling and publishing had one of its last great exemplars in them, and the men who came into the shop to buy books stayed in the publishing house to write them. Thus they drew on the whole resources of the University and an upper room in Number One became a common-room where young men and old men assembled to discuss books or God or social reform – but chiefly it would appear, God – before going into four o’clock hall.

Alexander Macmillan’s continued reverence for the poet Wordsworth was illustrated when he launched one of his most enduring publishing ventures, the periodical Nature. The first edition appeared on Thursday 4 November 1869: ‘Nature: A Weekly Illustrated Journal of Science’. Its masthead showed the Earth rising above the clouds and a quotation from Wordsworth ‘To the solid ground of Nature trusts the mind which builds for aye.’ The astute would remark that in the original poem it had been Mind which was capitalised rather than Nature; a sign perhaps that there would be little theology or respect for a Deity within the pages that followed. (The masthead would remain unchanged until the 1950s.)

In 1879, Macmillan & Co, now a successful London publishing house, would issue a volume of Wordsworth’s poems, edited by Matthew Arnold. The Preface to this edition, written by Arnold, began a revitalisation of Wordsworth’s reputation which, as with the other Romantic poets, had begun to fade: as a boy, Matthew had often met the poet while walking the hills around Windermere, and his father Dr Thomas Arnold had called Wordsworth a friend.

This week I have been reminding myself of the power and beauty of Wordsworth’s verse, partly to counteract my disappointment in the selfish, manipulative and controlling behaviour meted out to the women in his life, especially to his daughter Dora. This is detailed in a wonderful book which came out ten years ago, but I am ashamed to say I have only just read. Katie Waldegrave’s The Poets’ Daughters, which is the biography of Dora Wordsworth and Sara Coleridge, brings these two women alive, and reminds me yet again of the miseries that Victorian women endured: thwarted intellectual ambition, the expectation that they would sacrifice their lives to their families, the terrors of facing childbirth, and the inability of the medical profession to understand or treat feminine mental illnesses such as post-natal depression and eating disorders. Nevertheless in their sadly short lives, these two women achieved a great deal, particularly Sara Coleridge, now recognised as one of the most able interpreters and critics of the works of her less than coherent father. Well worth a read!