I’ve written before about families of achievement, and here is another one: let me introduce you to the Rathbones of Liverpool. The family story dates back to around 1720, when William Rathbone (the second William) moved to Liverpool from near Gawsthorpe, Cheshire, and set up as a timber merchant. Wood for building houses and ships was in great demand in this growing port, and the foundations of the family wealth were rapidly laid. You may be worrying that I am about to launch into a tale of the slave trade, but in fact the Rathbones were Quakers and philanthropists and there is nothing much to link them with the horrors on which so many Liverpudlian fortunes were built. In fact the Rathbone family, from generation to generation, were benefactors to the poor, liberal in their politics, and opponents of the slave trade.

William Rathbone (the sixth William) was a Liberal MP for many years, and invested back into his home town by establishing a training school for nurses, which led to the creation of a system of district nursing for poor people in their homes. This is the origin of the system which spread across the country. He helped to establish the Universities of Liverpool and of North Wales, and campaigned, unsuccessfully in his own lifetime, to end the iniquitous system of casual dock labour by the introduction of a weekly wage and a registration system. He also founded the Liverpool Provident Society to encourage thrift among the working classes. Rathbones survives to this day, and does a fine job managing the funds of the orthopaedic charity where I am a trustee. Among many fascinating Rathbone descendants there is Basil, of Sherlock Holmes fame:

and Harold Rathbone, founder of the short-lived but rather lovely Della Robbia Pottery based across the River Mersey on the Wirral.

However, the Rathbone I want to tell you about is Eleanor, daughter of the sixth William. One of the many excellent qualities of William was his support for women - which manifested itself in his recognition of the capabilities of his daughter, educating her, including a year away at Kensington High School, sending her to Somerville College, Oxford in the 1890s where she studied classics, involving her in many of his political and philanthropic ventures on her return to Liverpool, and ensuring that she would be an independently wealthy woman after his death.

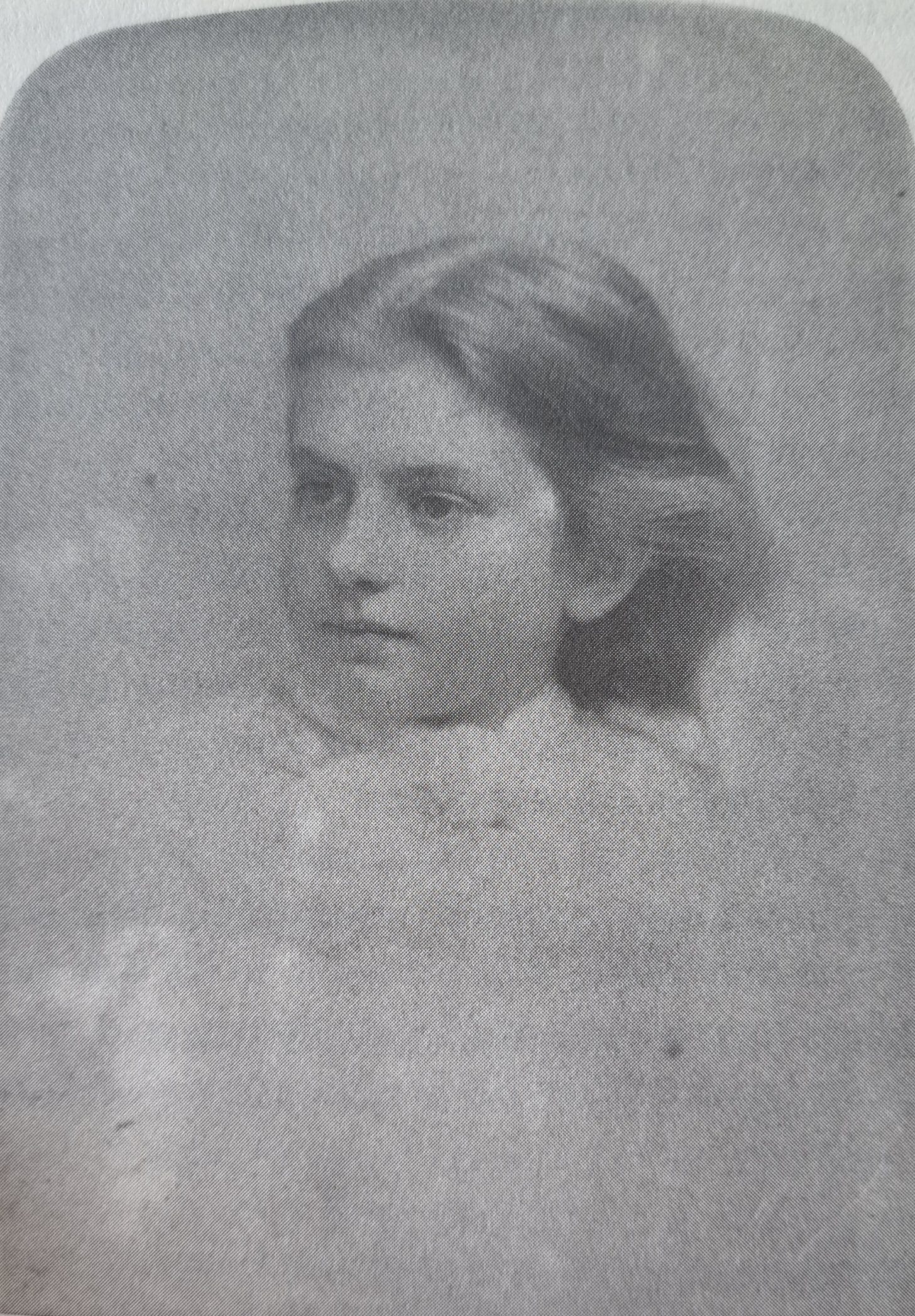

Eleanor was one of William’s eleven children, born in 1872. In 1896, newly returned from Oxford, she joined the Liverpool Women’s Suffrage Society, and was soon appointed to the Executive Committee of Millicent Fawcett’s National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (the NUWSS) - the organisation for the law-abiding type of suffragist, as the photograph demonstrates! At the same time she began work as a visitor for the Liverpool Central Relief Society, working among the poorest families dispensing aid and encouraging thrift. She became increasingly radicalised by the sights she witnessed, and began to teach herself social science, so that she could survey, analyse and describe what she saw and propose solutions based on real life experience, just as Octavia Hill and Beatrice Webb were doing elsewhere.

In 1902 she met the woman who would be her best friend and perhaps her partner for the rest of her life. Elizabeth Macadam was the Warden of the Victoria Settlement; these settlements were informal organisations that could be found across the country whereby volunteers effectively set up camp among some of the worst slums and tried to help and advise as best they could. When Elizabeth took over in 1901, the Victoria Settlement had 40 volunteers and spent around £500 per annum. In 1904 Eleanor became Honorary Secretary and the two women worked together to build it up - by 1910 the annual income was £1300 and there were sixteen separate branches all staffed by volunteers.

Slowly Eleanor’s thinking about social problems began to evolve, and to concentrate on the plight of the working-class wife and mother. If marriage is a system which is supposed to provide for women, why, wondered Eleanor, did it so often fail to do so? The number of married working-class women in paid employment was known to be falling: the 1851 census had shown that 25% of these women were in work - by 1901, this had fallen to only 10%, partly as a result of male trade union protectionism, partly because of the romantic idea of the husband as sole provider. Eleanor found her views diverging from the more usual left wing analysis of the misery of family poverty. It was all very well to say that the problem could be solved by better educating women, giving them the vote and protecting their rights to work and for fair pay - but what if there was simply not enough work to go round? and how did that square with society’s need for children to be born and reared in suitable surroundings? Rathbone began to argue that domestic labour and child-rearing should be recognised as work that needed adequate reward. She argued from her experience in the Settlement that when she and her colleagues considered everything the housewife, dependent on her husband’s wages, was expected to achieve, ‘the astonishing thing to us is not that so many women fail to grapple with the problem successfully, but that any succeed at all.’

In 1904, Eleanor published a Report of an Inquiry into the Condition of Dock Labour at the Liverpool Docks, building on her father’s campaign to improve working conditions there. She wrote ‘It is by the wives and children that the hardship of irregular earnings are felt most keenly.’ On the strength of this she was invited to give evidence to the 1907 Royal Commission on the Poor Laws, and her work fed into the 1912 Dock Registration Scheme. Now she began to campaign on two small but significant, and solvable problems - the allotment of seamen’s money to their wives while they were at sea, and the treatment of widows. Eleanor led a campaign to make it legal for shipowners and sailors to agree to pay wages on a weekly basis to the wives left behind. She also wanted the system changed so that widows with children to support did not have to apply for relief, as if they were in some way at fault, but were entitled to be paid an allowance for the service they were providing to society. Increasingly she got the point that as all widows were women, and none of them therefore had a vote, nothing was changing. She redoubled her efforts on behalf of the suffrage campaign (but never approving of the Pankhurst methods). In 1909 Eleanor was the first woman elected to Liverpool City Council, a seat she would hold until 1935.

During the First World War, the campaign to give women the vote was put on hold - particularly as it became obvious that women of all classes were playing a crucial role in the war effort that would have to be rewarded when peace broke out. In 1919 Millicent Fawcett retired as President of the NUWSS, and Eleanor took over, and with the achievement of limited voting rights for women (over the age of thirty) the organisation was rebranded the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship - NUSEC.

There now began one of those philosophical rifts that often seems to affect the feminist movement and caused a great deal of personal grief and unhappiness to Eleanor and others. During the War, a Separation Allowance had been paid to soldiers’ wives, to more than a million women - directly to them and proportionate to the size of the family it was supporting. It made an enormous difference - on practical grounds, the evidence showed that women in receipt of regular funds were better able to support their families, and there was a noticeable up-tick in children’s health. Secondly, the improvement in women’s self-confidence, their feeling of dignity and self-sufficiency, was very hard to put back in the bottle once the men returned and the money dried up. To Eleanor it became blindingly obvious that putting this on a permanent footing was the most important step that could be taken to improve the lot of working class women. In 1918, Eleanor published ‘Equal Pay and the Family: A Proposal for the National Endowment of Motherhood’. This was supported by the Family Endowment Committee she had founded the previous year, a cross-party body of men and women, who all believed that the care of young children should be treated as a form of work, and paid for out of the tax system. She tried to shake up NUSEC with the infusion of younger blood, proclaiming that the new feminist politics must ‘bubble freshly out of women’s own personalities and be impregnated with the salt of their own experiences’ - but she was unable to persuade the NUSEC committee who were hung up on campaigning for more political and economic rights. The argument was long-lasting and debilitating.

Meanwhile. Eleanor continued to hold to her belief, that one should never let an impossible ideal get in the way of an achievable good - and if she could not swing NUSEC behind her campaign for what we would now call ‘the family allowance’, she would keep chipping away, very effectively, at what she could achieve. Her first campaign was to have a major impact on the 1918 Representation of the People Act. Eleanor pointed out that although women had been voting in local elections fro several decades, it only applied to householders - ie the spinsters and the widows, not the wives. There was initially no intention to extend the ‘every woman over 30’ rule to local elections, until Eleanor pointed out the illogicality of wives being able to vote for an MP, but not for their local councillor. She got the Act changed. This Act not only gave the parliamentary vote to eight million women over the age of thirty, it quadrupled the female local government electorate. Policies that affected women would slowly begin to become more important to political parties.

Eleanor continued to combine lobbying work with practical action. Back in Liverpool she set in motion the ‘Personal Services Society’, a pioneer of what we would now recognise as social services, but staffed by several hundred volunteers, offering financial support, legal advice, even marriage guidance. It continues to this day, now called the PSS and operating out of Eleanor Rathbone House.

In 1924 Eleanor put all her research and her arguments for the family allowance system into a masterpiece of a book, The Disinherited Family. She pointed out the fallacy of the argument that working men are paid a family wage with which to support their wives and children - as the same wage was paid to the carefree bachelor. Women and children were supposed to be supported out of the same portion of a man’s wages that a bachelor could choose to spend on his dogs or his pigeons. Her arguments went beyond the provision of income, to the cause of better family planning:

Although no economic provision is made for the children, the mother responsible for their care is shut out by her poverty from the knowledge that would enable her to control and space their births, knowledge that is at the disposal of every woman able to pay for it.

At the LSE, an academic called William Beveridge read it and pronounced himself completely converted. Eleanor began to realise that she had so much to say, she should look for a national platform on which to say it. In 1929 she was elected to the House of Commons as an Independent member, representing the Combined English Universities.

If you thought what Eleanor had already achieved was pretty impressive - just wait for the next episode!

To be continued…

THIS is based on my own researches, but also on an excellent biography by Susan Pedersen: Eleanor Rathbone and the Politics of Conscience

Cannot wait for the next episode.

Really enjoyed this, thank you. Have you read any of Eleanor's work? It sounds like some of it could offer a useful framework or vocabulary even for today.