‘My darling Roy, I’m afraid that our married life is not starting as well as it might. Ever since the day we were married you have been full of grievances against me. On Jan 20th you were thinking that I ought to give up the Ministry of Labour and come and live at Bletchley; on Jan 29th you were thinking the same thing, with the additional grievance that if I couldn’t or wouldn’t give [it] up now I should at least give it up as soon as possible after the War. On Feb 4th you were angry because I didn’t come to meet you; on Feb 5th you were angry because I didn’t come to Euston with you and wasn’t in when you phoned. Behind all these grievances is the feeling that I don’t love you as much as you love me. If I did I would show it by coming to Bletchley and finding a part time job. It makes it all the more sad because I do love you with all my love. If my love is inadequate you shouldn’t have married me.’

This extract is from a letter in the archives of Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, from his wife of less than three weeks, Jennifer. It makes for terribly sad reading, especially as it is one of the very last pages in a huge folder of affectionate, sometimes passionate letters that Roy Jenkins and Jennifer Morris had written to each other, week after week, from the summer when they met in 1940 right through to their fairy tale wedding in The King’s Chapel of the Savoy, off the Strand, on 20 January 1945. Jennifer had graduated from Girton College, Cambridge in June 1942 and had been working full time in London ever since.

The letter continues: ‘You know well that I am not the kind of person who would be satisfied with housekeeping and cooking.’ As long as the Ministry of Labour would continue to employ a married woman, Jennifer wanted to stay there, and when the war came to an end and she had to leave (the marriage bar swinging into action and chucking hordes of married women back onto the labour market) she wanted to find another job. ‘You should also know that it is very difficult for a woman (merely because she is a woman) to get an interesting job. …You also knew that before we were married. If you didn’t like it you should have said.’

Over the past month or so I have been immersed in the archives of two other women, Edna Healey and Mary Stewart, both of whom, like Jennifer spent much of the war writing several times a week to men they loved, who had been called up for military service. If I had imagined, bearing in mind the circumstances in which these women found themselves, that they would be writing passionate, desperate letters of love and fear, I was sadly disappointed. All three women fill huge chunks of their letters with the mundane, the ordinary, the nuisances of civilian life in wartime - boring jobs, irritating office politics, the time spent sitting on cold miserable railway stations waiting for trains, the weather, enlivened by occasional trips to the cinema or the theatre. They rarely talk of their love, and making plans seemed to be tempting fate. The war dragged on and on, and there were only so many times these women felt they could write a letter baring their soul, or sharing their dreams.

Of course, for Denis Healey serving as a Beachmaster in Italy, any news from home was welcome. I imagine that he wanted to be kept cheerful and reassured that life was continuing just as he had left it. Michael Stewart, serving with the Intelligence Corps in the Middle East, had a wife, Mary, who was an officer in the WAAF, and as they were both moved around from posting to posting, keeping in touch at all seemed fraught with difficulty. Many of their letters begin ‘I don’t know if you will ever get this…’, hardly conducive to sharing affectionate thoughts. Roy Jenkins, meanwhile, was stationed with the codebreakers at Bletchley Park, so Jennifer did not need to worry about his safety - in fact, working as she did first in an armaments factory in North London and then in Whitehall, she was probably more at risk than he was.

Jennifer had spent the first part of 1939 living in Paris, having secured herself a scholarship to read History at Girton College, Cambridge. Looking back, she remembered this visit as one of the happiest times of her life, staying with a French family for five months, learning the language by speaking it every day, going to the theatres and galleries, making English and French friends. She attended lectures at the British Institute and the Sorbonne out of interest, but felt fancy free, with no examinations to worry about. Six months of freedom and independence living like this gave her a great deal of confidence for tackling Cambridge in the autumn.

She arrived home in the early summer, in time to join her parents and younger brother David on what would be their last holiday as a family in Cornwall. George Parker Morris, Jennifer’s father, soon to be knighted for his war work, had been appointed Town Clerk to the City of Westminster in 1928. Perhaps unsurprisingly he chose not to live in the area for which he was responsible, but in the fashionable and slightly bohemian Hampstead Garden Suburb. Preparations for war had been under way for some time: by September 1938 more than a million feet of trenches for bomb shelters had been dug, zigzagging their way across the parks of London, and plans were well advanced for underground air raid shelters, and for the evacuation of children to the country. As the clouds darkened in Europe, Parker Morris headed back to his office early from the holiday, leaving the family to drive slowly home. Jennifer recalled that they got back on 3 September, just in time to hear the declaration of war and the first air raid warning. Within a year, the Morris family would relocate to Henley-on-Thames, away from the bombers.

Jennifer arrived at Girton in October 1939. Term was delayed by a week to allow the staff to put up blackout blinds or paint out the windows in all the common areas: students were asked to supply their own blackout material for their bedrooms. Already the City seemed strangely deserted, so many young men had been called up or volunteered to fight. Nevertheless she threw herself happily into college life, and soon had made friends with another first year History student, Jane, daughter of the well-known Fabian and socialist intellectual, GDH (Douglas) Cole. Together Jennifer Morris and Jane Cole joined the University Labour Club, and made plans to spend the summer, firstly at a Fabian Summer Camp to be held at Dartington Hall in Devon and then fruit-picking as part of the war effort in Evesham.

The two weeks in Devon would change the course of Jennifer’s life, as it was here she met and immediately fell in love with a young man studying at Oxford University. Roy Harris Jenkins was just two months older than Jennifer, and studying PPE at Balliol College, Oxford. He was the only child of Arthur and Hattie Jenkins, and came from the mining community of Pontypool, South Wales. His background was more working class than Jennifer’s although, like the Morrises, his father’s recent rise to senior political office was propelling the Jenkins family into the circles of power and influence. Arthur Jenkins had left school to go down the mines at the age of twelve, but soon became an official of the National Union of Mineworkers, and carried the honour of having been imprisoned during the National Strike of 1926. In 1935 he was selected as Member of Parliament for Pontypool, and soon caught the attention of the newly-appointed Labour Leader, Clement Attlee, the two men sharing views on the danger of Fascism and the need to re-arm. By 1940, Arthur was acting as Attlee’s Parliamentary Private Secretary, and in May 1940, when Attlee entered Churchill’s Coalition Cabinet, Arthur’s rise to political influence was assured.

Roy was always academically gifted, winning a scholarship from his primary school to the local grammar school in Pontypool. He went up to Oxford in 1938, a year earlier than Jennifer, encouraged to apply by his father who had spent time in the city at Ruskin College, and helped by a year at University College Cardiff preparing for the exams. Somewhere along the line he had eradicated all traces of his Welsh accent. As a keen follower of his father’s career, and of Labour party politics, Roy was well aware of GDH Cole and his reputation among Oxford politics students. Once at Dartington he quickly introduced himself to Cole’s daughter Jane, and hence to her friend and companion, Jennifer Parker Morris. The attraction was immediate.

At the end of the camp, a sign of how quickly the bond had formed, Jennifer and Roy left Dartington together. She was on her way to pick fruit in Evesham as a contribution to the war effort, and had changed her plans to make the journey via Roy’s home in Pontypool. They were just nineteen years old, but their love affair began that summer, and can be carefully traced in a long and detailed correspondence preserved in the archives of the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The first letter in the file is from Jennifer in Evesham, dated 10 August 1940, and is mostly full of complaints about the train journey, which had been long and involved changes in Hereford and Worcester – a journey that can only have been undertaken in the enthusiasm of young love. ‘Evesham is absolutely packed – BBC, soldiers, evacuees etc, you can’t move. When I arrived I went to about four shops looking for some dungarees, and eventually found one pair – the last – which I bought though they’re really too small…Things are going to be pretty grim especially till my friend arrives, which I hope to God she does’.

By September the couple were swapping letters almost daily, and trying to arrange to meet again when Roy returned to Oxford, if Jennifer could find a friend to stay with. Jennifer’s next two years at Girton would be punctuated by complex and unpleasant cross country train journeys to Oxford to see Roy, who had lodgings at 2 St John Street. Dodging air raids, hanging around draughty waiting rooms in Rugby or Bletchley, Jennifer was forever terrified of missing her college curfew. She would write to him later ‘You know I think I’ve loved you ever since that gate at Dartington – it was quite surprising how much I missed you at Evesham.’

In June 1942 Jennifer left Girton, a good second class degree under her belt, and went straight to work at an armaments factory managed by Hoover in North London, where she spent eight months in the personnel department. By 1943 she had picked up more congenial and stimulating work in Whitehall, at the Ministry of Labour. She wrote to Roy, to whom she was now unofficially engaged (he couldn’t afford a ring):

My work will be mainly in connection with two inter-departmental committees under the chairmanship of Lord Hankey, on training and resettlement of people of secondary school standard…I have to do a 51 hour week on average, but I think that includes time off for lunch so it’s not as bad as it sounds. One can apparently take 1.5 hours off …it is quite convenient from Bounds Green. I won’t bother to move, as the office is near Lincolns Inn. We don’t have anyone under us as all typing is done by a typing pool but we are quite high up and treated politely…we appear to have lunch at the same table as the bigwigs …

However the pressure of work, of London life, and of rushing to see Roy at every available opportunity, began to tell on her health. She moved back to Henley to live with her parents, and in May 1943 Roy received a letter from her father full of heavy warning;

My wife and I are both worried that Jennifer is still so far from well and we want your help. It is important that she should make a success of her new post, as unless you are especially fortunate after the war she will have to maintain herself for some time…she will have to get back to the robust health of her Cambridge days and as she has a long week she will not do that unless she gets a proper amount of fresh air and rest at the weekend. We both realise that you will probably be going abroad before long and that you and she are desperately anxious to see as much as possible of one another in the short time available, but we want to ask you both to study her health in arranging your meetings. You can stand up to long journeys at the weekend and we shall welcome you here as often as you can come. But for Jennifer to go, for example, to Bristol and back today…travelling at the weekend can only be done at the expense of her health and her work. Tomorrow, instead of being fresh and vigorous, with a calm clear mind, she will be tired, her brain will be clouded and sluggish, and she will not be fit for her work which demands much greater application than her job at Hoovers.

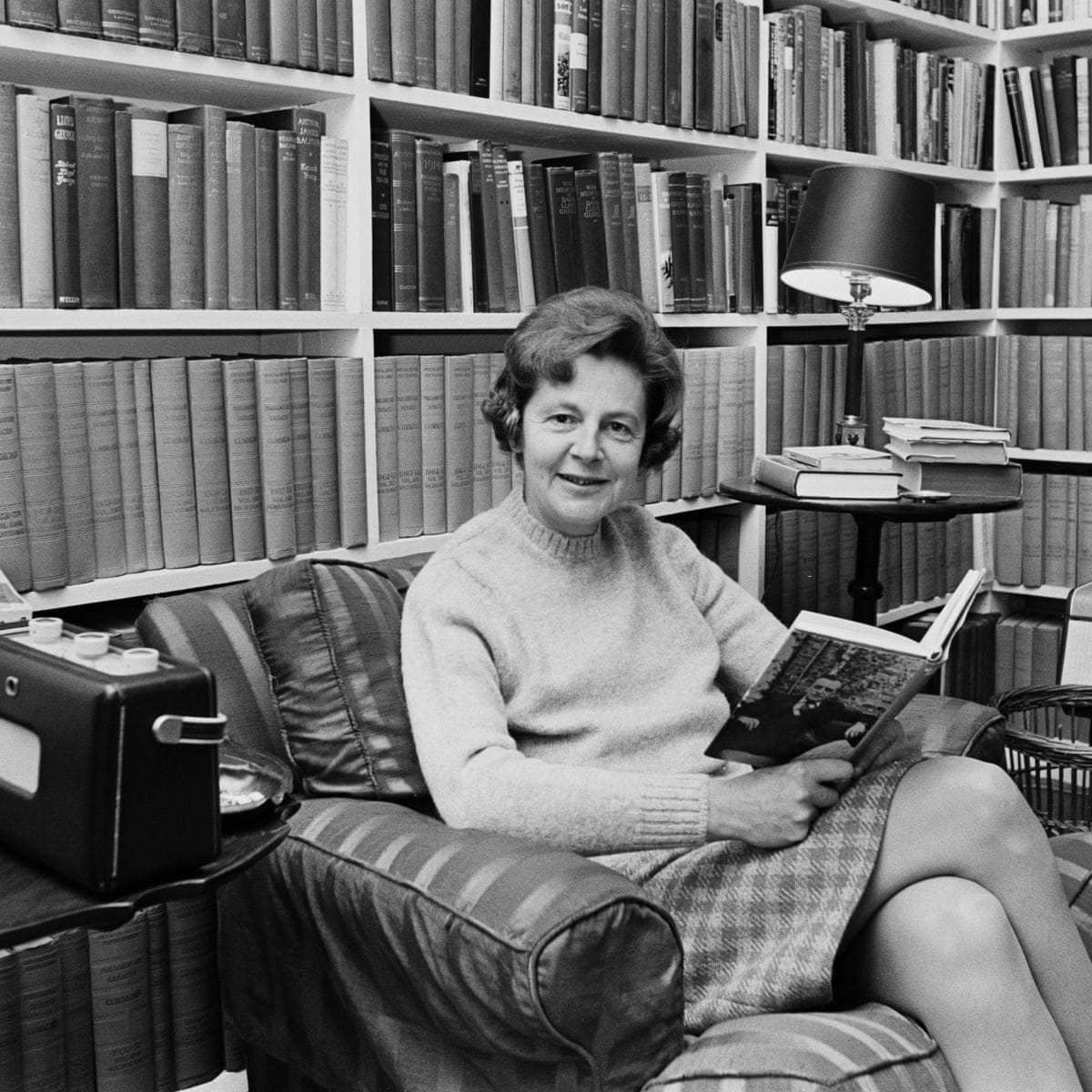

Whether or not ‘highly-strung’ Jennifer, as her father referred to her, was in any way deterred from seeing Roy as often as she could, possibly to the detriment of her health, at least Roy never was posted abroad. By 1944 they were discussing plans to marry as soon as they could persuade their parents to let them, and Roy was looking at opportunities to be selected as a Labour Party candidate for the next election. Significantly for Jennifer’s future career, that was the year she began to work with Michael Young, a former tutor at Dartington Hall, now in charge of PEP, the Political and Economic thinktank making plans that would be crucial to the Labour Government of 1945. She stayed in Whitehall until 1948 when she started a family - but in 1957, when Young founded the Consumers’ Association (the publisher of Which? magazine, among other things), he invited Jennifer to join the Board, and in 1965 she took over as Chair, a role which would lead to many other important and interesting roles in public service, including chairing the National Trust. To quote from her obituary in The Guardian:

After a period as a member of the executive board of the British Standards Institution(1970-73), and the Design Council (1971-74), in 1975 she went to the Historic Buildings Council for England. Membership of the committee of management of the Courtauld Institute (1981-84) and the Ancient Monuments Board (1982-84) followed. Formerly secretary to the Historic Buildings Commission, she later served as its president (1984-85). She was a London juvenile court magistrate and a director of both Sainsbury’s and the Abbey National building society. In 1985 she was appointed DBE for services to ancient and historical buildings.

It is very unlikely that even Roy Jenkins would have been able to stand in the way of such an ambitious, and accomplished, woman. ‘If you didn’t like it, you should have said.’

I hope so....

This was a glorious read thank you Sarah. So great to discover Jennifer. When my parents first married they named their pet cat Jenkins (after Roy) but I’d like to think it was after Jennifer now.