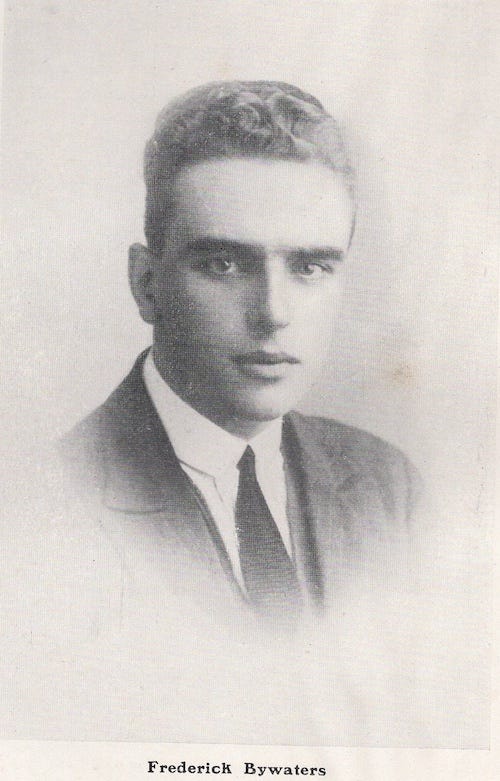

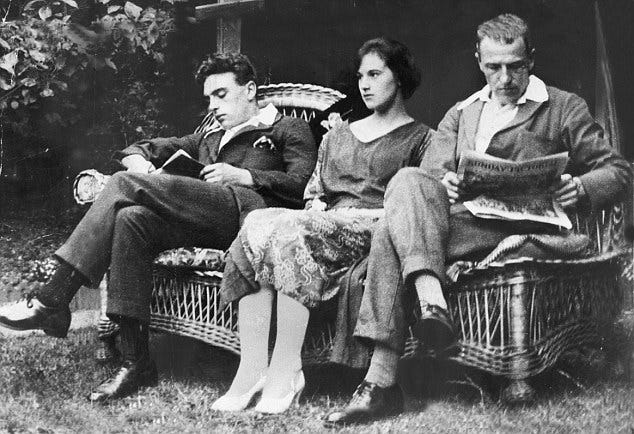

Last week, in my quest to immerse myself in the literature of English women between the wars, I pulled from the shelf my battered copy of a Virago classic, F Tennyson Jesse’s A Pin to see the Peepshow (possibly no longer in print?). This is a book I bought and read in 1986, but had never returned to. Spoiler alert: it is definitely not a story with a happy ending. It is the (only slightly) fictionalised account of the Thompson/Bywaters murder case from 1923. The original case has been expertly written about by many people, including in two books and substacks by

1 I don’t want to tread on anyone’s toes, so I won’t revisit the actual facts of this appalling miscarriage of justice. But I do want to talk about the literary masterpiece that it inspired.

The first half of the novel is an absolute delight. Julia Almond is not the brightest of girls, but there is something about her that makes her stand out from the crowd.

She wasn’t pretty, except occasionally. She was very short sighted, and she saw the pallor of her skin, the narrow brightness of her eyes and the gleam of her hair through a haze that lay like a bloom over everything at which she looked. But she was right in believing that there was no other girl in the school who gave back quite that brilliant reflection.

When the story opens in 1911, Julia is a schoolgirl living in a west London suburb. She is the only daughter of ineffectual, unambitious lower middle class parents, who are only too happy for her to give up her education at the earliest opportunity and get an unpaid apprenticeship at a smart ladies’ outfitters. To everyone’s surprise, including her own, Julia thrives in this workplace, demonstrating an admirable head for business, a winning way with customers, and a flair for fashion and colour. Her life at home may be drab and uninspiring, but at work she moves among the smarter, wealthier classes, and the vague romantic dreams that filled the head of the schoolgirl take on substance.

She stood for a moment while the evening light brimmed the room like the last of a high tide; and it seemed to her that she had at least achieved something. It wasn’t everybody who could work hard and get a good business together, especially when they had started as an apprentice as she had done. yes, she had made all this, and she had made the new Julia that stood looking at her from the full-length mirror. This Julia in the smart little black suit, with the little black lace hat that came down to her blind but lovely eyes - she had made this elegant thing called Miss Almond.

At this point, Julia could be set for life and we are rooting for her to succeed and find happiness. We know that she has drive and ambition: yes, she can be reckless, she is self-centred, but she is desperate to love and be loved. Throughout the novel the only creature that truly returns her affection is her beloved dog Bobby. To my mind, there is nothing terribly wrong with anyone who loves a dog as much as Julia loves Bobby. But halfway through my reading, I suddenly began to remember why this was a not a novel that I had ever gone back to: I felt again my stomach contracting with dread as Julia, who aged nineteen had grasped at marriage, to a man some fifteen years her senior as a way of escaping from the parental home, meets and falls for a younger man, Leo Carr. I want to shout through the pages and warn her to keep away, that disaster is looming. Leo has nothing to offer you!

On the one hand, so much is going right for Julia at this point. She is extremely successful at L’Etrangere, so much so that she is trusted to travel to Paris regularly and alone to choose patterns and fabrics to be brought to the London store. She is earning more than her husband, the dull and unimaginative Herbert Starling, and is thus able to negotiate a certain degree of domestic freedom - even though Julia is married she is able to keep working, they can afford a maid, and as she has banished Herbert from her bedroom, there is no chance of a pregnancy to spoil her career. But she has never lost that schoolgirl dreaminess, and her dislike of the increasingly insecure and pompous Herbert and his disapproving older sister Bertha makes her long to escape the house in St Clement’s Square.

Into her life strolls sex, in the shape of Leo, six years younger than herself, a fitter-mechanic on an aircraft carrier, someone who has seen something of the world of which Julia can only dream. Leo starts a flirtation, but is too young and too reckless to realise the effect that this will have upon poor love-starved Julia. Almost at once, Julia begins to reconsider her life and the choices she has made :

What a fool she had been to marry Herbert. Why couldn’t she have trusted life a little longer? Why hadn’t she had the energy and courage to break with her mother and the whole of the rest of the household at Two Beresford? But how would she have lived if she had? Girls earning as little as she had been earning simply had to live at home.

And here we begin to understand one of the messages that the author is driving through the text. This is the 1920s: if Julia had been of the same wealthy class as her employers, with a private income, she could have had an affair, bought a divorce and, even without a job, life would have continued. If she had been truly poor, of the lowest working class, she could have left Herbert and set up house with Leo, and as long as Herbert didn’t come after them, no-one would have been any the wiser. But Julia is caught in the middle - bound by the trammels of middle-class respectability, and without enough money to extricate herself.

The plot of the novel unfolds just as Edith and Freddy’s story did in real life. There is a brief affair, with very few opportunities for actual consummation, so Julia pours her heart out in a rather one-sided correspondence, in which every romantic fantasy she has ever read finds expression. One night Leo, the worse for drink, waylays the married couple as they walk home from the theatre, and before Julia has even realised what is happening, Herbert is dead on the pavement. And then the terrible nightmare begins: although Julia has destroyed Leo’s letters to her, he has kept all of hers, and they are full of wild suggestions that ‘we can’t go on like this’, ‘if only something happened to Herbert’, perhaps she could dose him with some of her own medicines…

The Court case of course gives Julia no chance. The Prosecution paints Julia as an adulterous Jezebel, who has led an innocent young man astray. Leo’s determined proclamation that Julia knew nothing about the attack in advance, simply serves to make him seem heroic. In any case, no-one believes him, they think he is just loyally protecting his evil mistress. So Julia will be hanged for a crime that she might have fantasised about, but did not plan and did not commit. As somebody says, if they can’t hang her for murder, they will hang her for adultery.

The last chapters of the book are almost unbearable: Here Tennyson Jesse launches the most excruciating attack on the system of capital punishment that I have read. I can never forget the depictions of Julia screaming and clawing at the walls of her cell. Eighteen women were executed in England between 1900 and 1955, when Ruth Ellis was the last woman to be hanged for murder. In five of these cases, the alleged motive was ‘love’.

All over the prison, and in the homes of those to do with the prison, the uneasy consciousness of Julia Starling, and of the approach of nine o’clock next morning, seemed to hold the very air, gripping it as a frost grips it…You couldn’t face with equanimity what was to take place at nine. Nine, when so many thousands and thousands of people would be sitting down to their eggs and bacon, when many more thousands would already be on their way to work. And nearly every one of them thinking…Is it over yet? Not liking to look at their watch or clock lest it should be the actual minute. Not wanting to look until the hands stood at five minutes past, when they could draw a deep breath and say more comfortably: “Well, it’s all over now, anyway.”

But for everyone who cannot bear to think about what is happening within the confines of the prison, there are many more who are drawn to the spectacle:

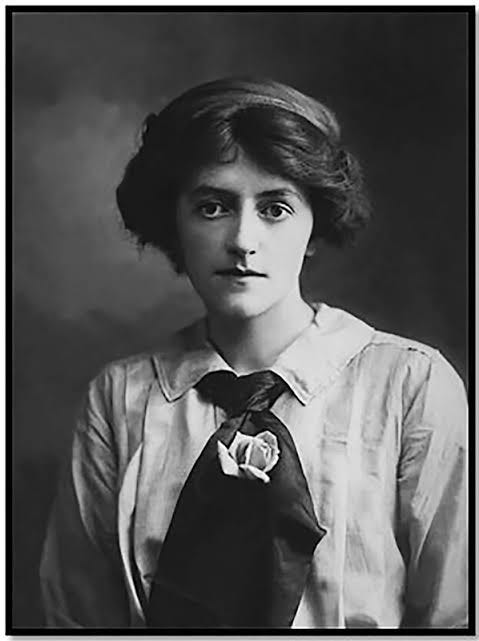

My Virago edition tells me that Fryniwyd Tennyson Jesse (1888-1958) was the great-niece of Alfred Lord Tennyson, that she studied art at the Newlyn School in Cornwall, that in 1911 she started to work as a journalist, writing for The Times and the Daily Mail, and one of the few women to report from the front line. She married a playwright, HM Harwood, and they regularly collaborated on shows that ran in the West End. She became a brilliant criminologist and an acclaimed authority in the field. She wrote A Pin to see the Peepshow in 1934, her best-known but not her only novel. In it she absolutely skewers the hypocrisy of her times and society: the double standards applied to men and women with regard to sexual activity; the terrible dilemmas facing women who wanted both financial security and passion; the misery of women’s lives who have no access to the divorce courts or to reliable family planning and health services. Julia had little time for the suffragettes of her youth: ‘the whole question bored her profoundly’. But it is lucky that so many women were prepared to fight for the right to vote, and thus to change the lives that their sisters and daughters lived. If Julia had been born just half a century later, her story would have been so very different.

Great read. I will dive into Laura's piece next! This reminded me of a great book I read many years ago, Eve Was Framed by Helena Kennedy. Shocking how women were treated by the "justice" system. I love the way you weave it all together, highlighting the women involved; the writers, all the way through to this piece and Laura's. Brilliant.

Thank you for the link Sarah...

And for writing about this WONDERFUL book, which one always prays will end differently. What an interesting woman FTJ must have been.