We may all be equal in death. But many thousands of Britons have given everything in this war in order that we might be equal in life, too.

Mary Stewart enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Airforce (the WAAF) in December 1941. She was rapidly recognised as officer material and commissioned as Assistant Section Officer in June 1942. Over the next eighteen months she served in six separate locations around England. By August 1943 she was working as a Psychiatric Assistant at WRAF Newtownards in Northern Ireland, then after a short stint in London HQ she was sent to RAF Eastchurch, in Kent, where she was stationed as preparations began for the victory celebrations. Her preference would have been to spend VE Day quietly at home in London with friends and family, especially as her husband Michael was still serving overseas in the Intelligence Corps. However, as an officer she was expected to be on base, apparently to protect the younger WAAF women from potential onslaught by inebriated males. Mary was now a woman in her forties, and finding military discipline more than a little tiresome: ‘If we have been genuine in our fight for democracy, it should not be necessary to treat us either as schoolchildren or political gangsters when peace is declared.’

In the event, VE Day (8th May, Mary’s 42nd birthday) passed off very happily. ‘After dressing in our best blue, and eating our Victory Egg, we strolled down to our offices about 10 or 10.30am. Mac and I went via Sick Quarters to collect a cup of tea and some hangover pills to prepare ourselves for all emergencies.’ Mary, as an officer, was permitted to stand on the platform behind the Commanding Officer to watch the march past. The CO said a few uncontroversial words, there was a service with hymns, and then lunch in the mess with drinks and sunbathing in the garden in the afternoon. All very civilised. Mary had plenty to think about: she needed to consider her options for life after she left the WAAF. She still had a job open for her as a lecturer in the Workers’ Education Association, but was only too aware that the freedoms and responsibilities given to women during the War might be rolled back now that the men were coming home. Just the month before, she had been interviewed for a job as a Civil Service Commissioner, and it had gone very badly. She had been made to feel that she wasn’t even qualified for the job she had been doing in the WAAF, and in the end, in her own words, she had dug her own grave. ‘Did she feel that a male candidate would talk as freely to her, a woman, as he would to a male psychologist?’ ‘No,’, she had replied. End of story. She had been the only female candidate they had even interviewed that day. Life back in civvy street would continue to present challenges to a woman, even one with qualifications, who wanted a career.

‘Darling, it’s Michael’….just three days after the VE Day celebration, Mary was sitting drinking coffee after lunch when she was called to the telephone. She could hardly believe the news - her husband had left Cairo on a flight the evening before and was already at Waterloo Station. All Mary’s friends rushed to help her get ready: ‘Pip and one or two other men wheeled a handcart to the front of the Mess and offered to push me up to London in it.’ More usefully, the other WAAF officers helped her pack and the Wing Commander drove her to Sittingbourne to catch a train. For hours the couple tramped the streets of London looking for a hotel to spend the night, but luckily the receptionist at the Russell Hotel had a soft spot for men in uniform ‘I can let YOU have a room, Captain.’

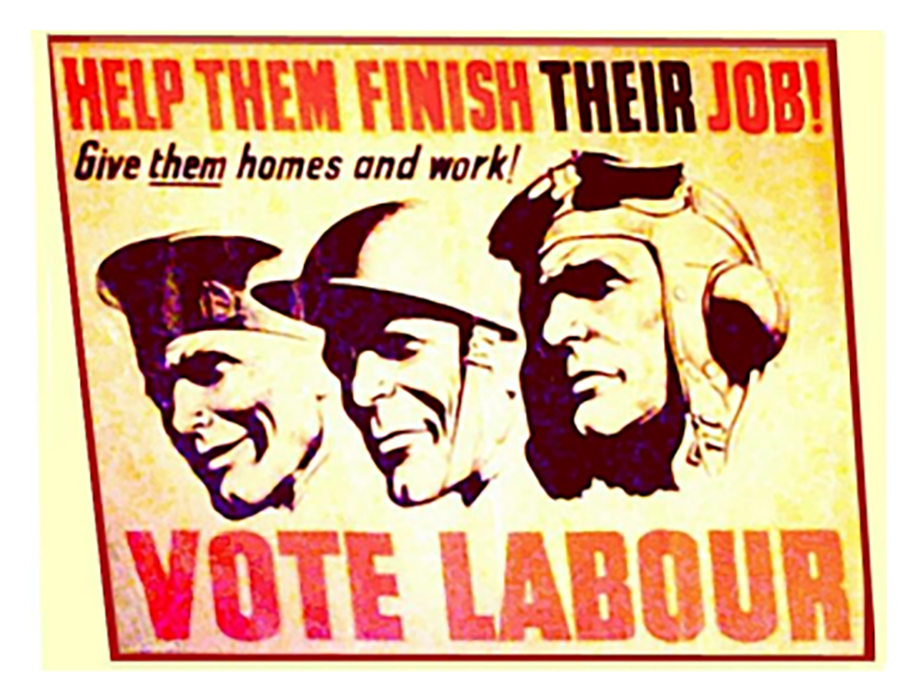

Michael was one of the many returning servicemen hoping to be sent to Parliament in the forthcoming General Election. He had first stood as a Labour candidate in Lewisham in the early 1930s, and in 1936 had been adopted by Fulham East. His opponent, the sitting Tory MP, was William Astor, son of Nancy Astor, and soon to be the Third Viscount Astor, but his majority was small and Labour had held the seat in the recent past. In 1945 the tide was turning Labour’s way, even if the political establishment had not fully realised the impact the war was having. By 1942, forty per cent of the people interviewed by Mass Observation were saying that their political views had changed. Air Chief Marshall ‘Bomber’ Harris told Churchill that eighty per cent of the the RAF would vote Labour. As the Daily Mirror wrote in an editorial in January 1945 ‘We may all be equal in death. But many thousands of Britons have given everything in this war in order that we might be equal in life, too.’

The Labour Party had been part of Churchill’s coalition since May 1940 - and by 1945 there were seventeen Labour ministers serving in the Government. The party leaders, Clement Attlee and Herbert Morrison, were firmly associated in the public mind with success and victory. The public’s appetite for radical social change had been whetted by the publication in 1942 of the Beveridge Report which called for the introduction of a Welfare State, and Labour party members, and voters, were clamouring for its rapid introduction into law. Finally, living through the war, latterly as an ally of the Soviet Union, had opened people’s minds to the idea that socialism, nationalisation of key industries, and state planning, were not necessarily bad things.

Michael Stewart hurried from London to the Labour Party Conference being held in Blackpool. There the National Executive Committee voted to withdraw from the Coalition Government. Attlee hoped to delay an election until after Japan had been defeated, whenever that might be, which would allow more time for an up-to-date electoral register to be compiled. But Churchill, elated by the popular response to VE Day, called for an immediate dissolution of Parliament and on 5 July the country went to the polls.

There were 640 seats up for grabs - including 25 new constituencies created since the last General Election. The electorate was looking very different as well: twenty per cent of voters were new to the register, having been too young to vote in 1935. More than 60 per cent of this generation would swing to Labour. Nearly two million men were serving abroad - the result of the election was delayed until their votes had been counted. The outcome was finally announced on 25 July: on a 73 per cent turn out, significantly higher than previous elections, Labour had won 12 million votes, giving them 393 seats. One of these new MPs was Michael Stewart. Mary noted in her diary ‘Yesterday Michael was returned to Parliament together with nearly 400 other socialists. A silent revolution that may be almost as significant as that of 1688.’ In the first days of August, Mary was discharged from the WAAF, and a week later she was sitting in the Reading Room of the British Library, preparing her classes, regretting that she had just six weeks to catch up on six years of reading. Meanwhile Michael was appointed a Junior Whip in Attlee’s Government, and was on the road to the political career of which he had always dreamt.

And what of Mary Stewart? She could easily have resigned herself to the life of an MP’s wife, opening fetes and hosting tea parties. Of course, there was plenty of that to come. But it was never going to be enough to keep Mary occupied. She continued to teach psychology and sociology for the WEA but now she became more active in politics herself. She was a close friend of Barbara Wootton, an enthusiastic proponent of political, social and voluntary activity for women, who encouraged her to become more involved. For more about Barbara, here is a piece I wrote earlier this year.

Mary had hoped that she and Michael would start a family, but it never happened. So she turned her attention to the issues facing children and young people, perhaps driven by the experiences of her own youth. Her family life had been anything but happy. Herbert Birkinshaw was an unpleasant man, bullying and abusive. His temper drove Mary’s older brother to join the army at sixteen and then to emigrate. Isabel, Mary’s mother, was afraid of her husband and lived in a permanent state of anxiety. But she fought like a tiger to protect her children. Mary told Michael a story that when her little brother Bill was born, and Isabel was still in bed, with Frank aged eight and Mary aged two, their father had abandoned them in Barnt Green, south of Birmingham, and set off for Bradford. According to Mary, when Isabel realised what had happened, she ‘packed everything into a van and set off after him’, even though she had no money to pay the van driver. Nevertheless, although Isabel had to borrow from her relations at times to feed her family, she always found something to spare for anyone in more need, even if it meant her own children going short of food.

I don’t regret my childhood - I don’t even regret the cowardly traits it has left me with - I still dither inside when I hear people shouting in anger and I have to screw myself up to face an angry person. My own fears have made me understand the part played by fear in the world, and have given me a bond with people I might not otherwise have had. And from my mother I learnt how different the world might be from what it is. She is a delightful person… ‘To everyone according to his needs’ is the only rule she knows.

Mary had managed to escape from her father’s domineering personality by winning a place at grammar school, and a scholarship that took her to Bedford College in London. Building on these formative experiences, there would be three major themes to Mary’s career for the rest of her life: the health and welfare of children, the youth justice system, and education. In 1950 Mary was appointed to the Executive Committee of The Fabian Society, an organisation she would chair in 1963-4. On a more practical level she enrolled as a Justice of the Peace, became a Juvenile Magistrate, and chaired the East London Juvenile Court from 1956-66. She believed in a less punitive approach to young offenders, and made recommendations such as raising the age of criminal responsibility from eight to fourteen. I particularly enjoyed a letter she wrote to the Editor of The Times in 1961, on the vexed subject of what makes someone become a criminal:

In recent years have not sociologists perhaps given too much thought to the factors which produce the criminal, and too little to those which produce the law-abiding citizen? Well-behaved people, without talents or eccentricities to single them out from their fellows, are rarely the subjects of intensive scrutiny; yet among them are many whose triumphs in the face of misfortune might be a fruitful source of study. I have in mind parents whose children are happy and law-abiding in spite of gross overcrowding and a high delinquency rate in their neighbourhoods; child victims of broken homes who retain their warmth and balance in large institutions; the unaccountably well-adjusted members of families which are in the main highly neurotic or criminal. Such people are not difficult to find and would be far more cooperative as subjects of an investigation than the members of problem families and the inmates of prisons and borstals. The secrets of their success might well reveal to us truths which now evade us.

During the years that Michael served as Foreign Secretary, Mary found herself in the unusual position of having to travel, to entertain and to socialise at an international level, quite a strain for a woman many believed to be very shy. Meanwhile she had been appointed to chair the Governing Body of the Charing Cross Hospital, presiding over the construction of the new £15m building on the Fulham Palace Road, which opened in 1973.

In the New Year’s Honours List of 1975 the significance of her work was recognised when she was created a life peer, as Baroness Stewart of Alvechurch.

Mary Stewart died in 1984. You may be wondering why I have devoted so much time and ink to the wife of a politician who even the nerdiest of political students has probably forgotten. Among the personalities of the Wilson Cabinet - Denis Healey, Roy Jenkins, Jim Callaghan, Barbara Castle, Tony Crosland - Michael Stewart was a surprisingly diffident although highly effective minister, twice rising to the rank of Foreign Secretary, and yet most people would struggle to name him. So, here is my argument: that unlike any previous Cabinet, Labour or Tory, the Wilson Cabinet was rich with talent, intellect and personality, and supporting that talent were some of the most interesting, politically committed and independently-minded women of their generation. These were not women who sat at home waiting for their husbands with the dinner on the table. These were women with important responsibilities, with careers and conflicting demands on their time, and crucially with strong opinions that they were always ready to share. I can never prove the influence these women may have had on the ground-breaking social policies of the Wilson years, but I am going to keep bringing them out of the closet, and into the limelight that I believe they richly deserve.

This was fantastic Sarah. I am so pleased you are bringing them out , dusting them down and shining a beam on them. Such an incredible time in history and they had to deal with so much. And so capable.

I love that you continue to champion the people who have made such a difference to society without expecting or wanting reward or recognition for their achievements. I look forward to your future, excellently informative posts. ⭐️