Sometimes I disappear down a research rabbit hole, and emerge bearing aloft something much more wonderful than I had ever imagined. And it makes my day. One month ago I had never heard of Barbara Wootton, but then her name started to come up in connection with some of my Labour women, my dahlias, so I managed to find a copy of her autobiography, with the intriguing title ‘In a World I Never Made’. And I realised I had found a real gem.

The provenance of the title itself was very encouraging: I’m a great fan of AE Housman, and Wootton’s choice from his Last Poems seemed to tell me so much about this woman, that I will repeat some of it for you here:

The laws of God, the laws of man,

He may keep that will and can;

Not I: let God and man decree

Laws for themselves and not for me;

And if my ways are not as theirs

Let them mind their own affairs.

It brought a sad smile to my face, as I thought of Tim Walz and his ‘Mind your own damn business.’ Unfortunately, as Wootton has discovered, this sentiment is not always enough, we do not make our own rules, but find ourselves in strange times, having to abide by other people’s moral codes, as she and Housman did:

I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made.

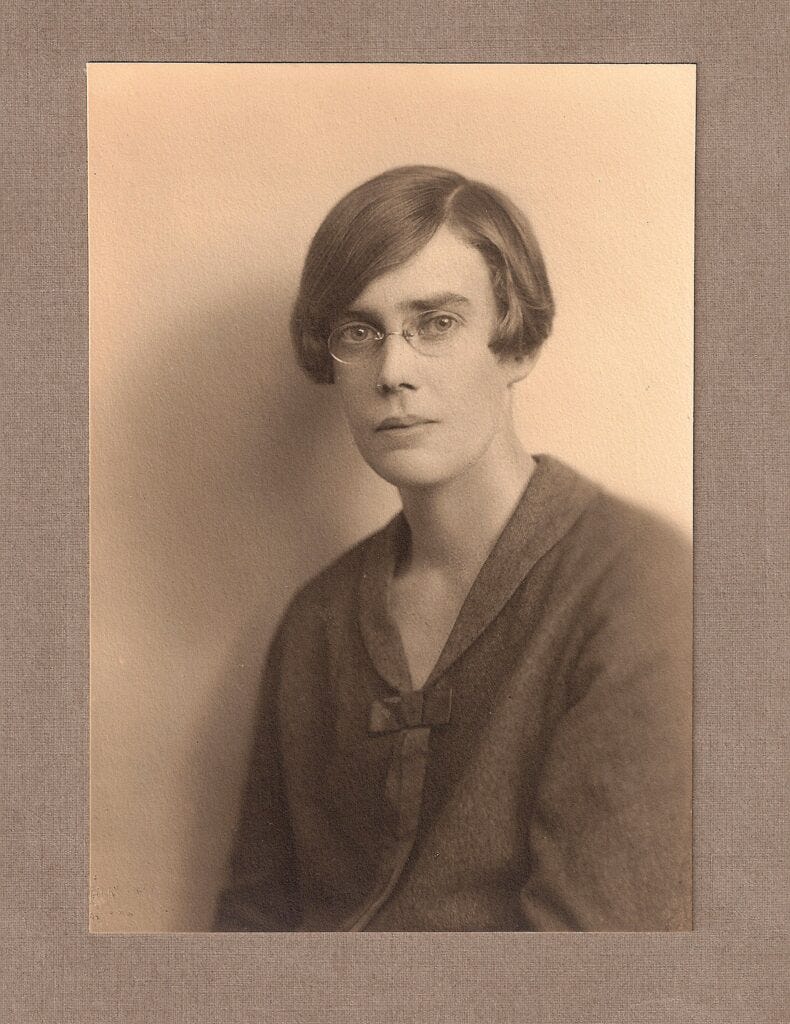

So who on earth was Barbara Wootton, and why is she not better known today? She was born Barbara Adam in 1897 to an academic family in Cambridge, the only daughter and third child of two classical scholars. One of her brothers was killed in the First World War, her other brother was a scientist who became a professor and a Fellow of the Royal Society. Barbara, however, was seen as a disappointment by her mother, who would talk about ‘my distinguished son, and my daughter who might have been distinguished.’ A quick summary of her life might suggest that her mother was using a very odd yardstick to measure her daughter’s success. Barbara studied Classics and Economics at Girton College, Cambridge, taught economics at Cambridge, became Principal of Morley College in London, then Director of External Studies for the University of London. She was at various times a Governor of the BBC, a colleague of William Beveridge, a friend of HG Wells, a founder member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, she served on four Royal Commissions, was the one of the first women to be created a life peer, and was the first woman to sit on the woolsack as Deputy Speaker of the House of Lords.

This illustrious curriculum vitae might suggest that her memoir would be serious and stuffy - and I will admit that the second half of the book consists of five long essays on serious subjects, analysing her experiences as a woman, a socialist, an agnostic, a magistrate and a public servant. But it is the first half of the book that I loved, as she writes with great humour and sometimes great sadness. There was much to sad about in her early life: her father died when she was ten, her brother Arthur was killed at the front in 1916. Shortly afterwards she herself became engaged to a friend of her brother’s, Jack Wootton, and in September 1917, when Jack was recalled to the front after recovering from injury, they were married, and spent just two days together at the Rubens Hotel, so that she could see him off from Victoria Station. Five weeks later she was informed that he had been killed in action.

There is one small passage which moved me greatly, because of how little, and yet how much, it said, about her grief. It is when she describes her engagement ring:

As for the ring, that was an unusual one, with an opal set in a cluster of rowan berries, designed and made by the hand of a woman craftsman introduced to us by Aunt Frances. Some fifteen years later I carelessly lost it in a hotel bathroom. All that I knew was that the name of the maker had been Laetitia Graham and that she had lived in Chelsea. Searching the London telephone directory I took a chance on a Miss L Graham at a Chelsea address; and was lucky. By this time Miss Graham was elderly and ill, but she remembered the original perfectly and generously agreed to make the replica which I still wear.

Twenty years later, through the Workers’ Education Association summer schools that she ran, Barbara met and married George Wright. He was younger than her, and had started in life as a London cabbie, a fact which the press found endlessly amusing, so that ‘Twenty three years after our marriage, when I was one of the first women admitted to the House of Lords, and George had not been near a taxi except as a passenger for nearly twenty years, I was pestered with requests for us both to be photographed outside the House, ‘standing beside his taxi’.

Barbara never had children, which she openly regretted, and although her marriage gave her great happiness and companionship, it ended in an amicable divorce after twenty-one years. ‘Neither of us perhaps was well-adapted to monogamous marriage…I am too much occupied with my own affairs…to make an easy marriage partner. George, on the other hand, was clearly a natural polygamist.’

Barbara’s life was full of the sort of extraordinary obstacles still placed in the way of women in the early twentieth century, and her determination to overcome them is inspirational to me. She took her final exams in economics in Cambridge in 1919 and was distinguished by passing out top of the list, with the highest mark. But she could not put the letters BA after her name, because Cambridge did not grant women degrees until 1948. Nevertheless she was given a post as a University Economics lecturer, although, as she was not a member of the University, (not holding a degree), the lectures were advertised as being given by a Hubert Henderson, with a footnote explaining that they would actually be delivered by Mrs Wootton.

Meanwhile, Barbara became increasingly committed to socialist politics. In 1922 she went to London to work as a researcher in the Labour Party headquarters: during the day she wrote notes for parliamentary candidates to use, and in the evenings she attended meetings to watch them in action. What she saw, she says, put her off ever standing for Parliament. She went from that job to Principal of Morley College, an adult education establishment, and then spent nearly twenty years as Director of Studies for the extra-mural school of the University of London. She began to travel widely, taking holidays across Europe and America. In 1932 she was invited to visit Russia:

Some of our experiences were mildly disconcerting. In the schools which we visited, the children, obviously suitably coached, used to greet us with the remark ‘So you come from England, where they beat the children.’ It would have been agreeable to have been able to deny the second half of this statement, but as it was the best we could do was to retort that in England we did not station a child with a fixed bayonet outside a children’s home, as we commonly saw in Russia.

I think that one of the things that attracts me to Barbara is her disdain for economists, despite having been one herself. I will freely admit that I studied the subject for two terms at university, never understood any of it, barely scraped through the exam, and have never touched the subject again. It is my firm belief that economists make things up as they go along, and if they happen to be right in any prediction, that is entirely down to chance. Barbara’s beef with her colleagues was their ‘inability to solve the grievous economic problems of the world, but also their ostrich-like habit of wrapping themselves up in abstractions as though those problems either did not exist, or at least were no concern of theirs.’ She took particular exception to Professor Robbins’ book ‘The Nature and Significance of Economic Science’, which she answered with a chapter ‘The Nature and Insignificance of Economic Science’, in a book entitled Lament for Economics, published in 1938. It certainly burnt her boats with the profession: from then on she referred to herself as a social scientist.

Wootton was often invited to lecture abroad, and tells a funny story about a well-paid trip to the USA and Mexico accompanied by George, where she ‘enjoyed the rewards of inferior status’. They had to get income tax clearance from a US official, who addressed all his remarks to George and foolishly overlooked his wife:

‘You have been here on vacation, Mr Wright?’ ‘Yes’, said George truthfully. ‘And you have had a good time?’ ‘Yes’, repeated George, with mounting enthusiasm. Then, in very sceptical tones, came the final question ‘I don’t suppose you’ve earned any money?’ ‘No’, said the still completely truthful George.

I would have owned up, had the question ‘Did your wife earn any money?’ been put. But chattels, I thought to myself, are entitled to be chattels.

During the Second World War, George was a registered Conscientious Objector, and Barbara threw her energies into a movement aimed at preventing future wars, called the Federal Union. Of course it came to nothing: ‘To the hard-headed practical men we were all alike; a hopeless lot of woolly idealists, if not actually near-traitors. Of course the practical men were right; they always are, if only because they can make themselves so. Practical men in positions of power can always demonstrate the impracticability of idealistic proposals by the simple device of making sure they are never tried.’

In later life, Barbara retired to a barn she converted at Abinger Common in Surrey, and there she lived alone, with the companionship of two rescued donkeys, Miranda and Francesca. She was happy to look back at a life that had been full of interest, of variety, of professional success. As she wrote ‘Masculine parallels would be easy enough to find, but as a woman’s story it is more unusual. This story…is not to be read as evidence that women are now equal partners with men in shaping the pattern, and enjoying the fruits, of our civilisation. We are not. If we have come a long way, we still have far to go.’

I have a recollection of her talking to the Marshall Society in Cambridge in the late 1970s or early 80s. Her contribution to the development of the welfare state and some more technical economic reflections can be found in this paper:

https://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/research-files/repec/cam/pdf/cwpe2246.pdf

Absolutely fascinating-I remember the name from my childhood. If Daniel Craig plays Wright in film version I think Helen Lewis should branch into acting to play the Barbara as a young woman