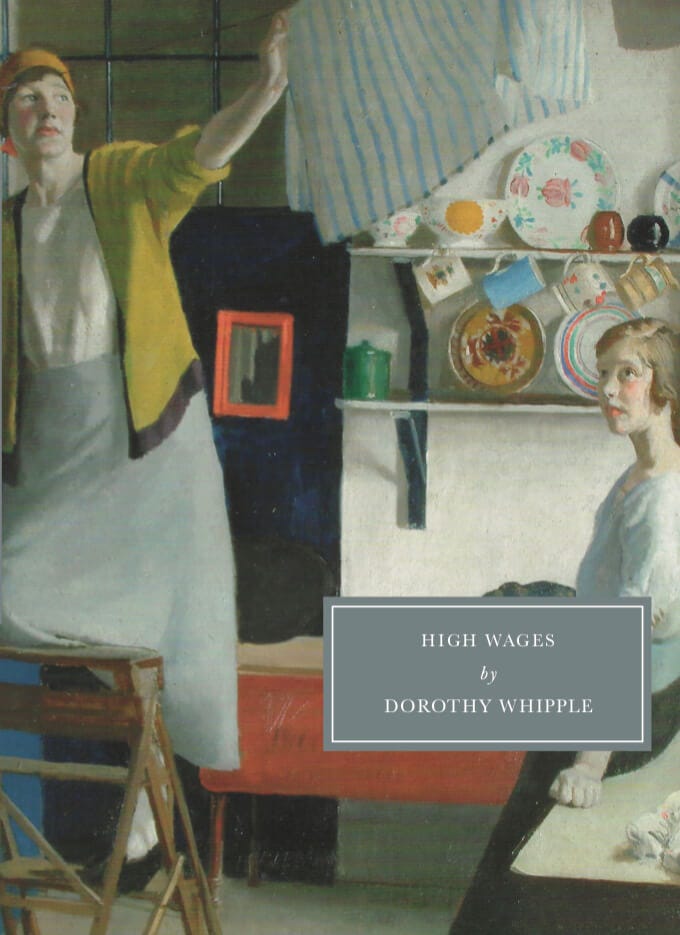

This week I have had the delight of reading another novel by Dorothy Whipple: High Wages was her second book, published in 1930, and now of course in a lovely Persephone edition. In fact, this was my first experience of a Persephone audio production, as it would be more accurate to say that I listened to an actress called Sara Poyzer, fresh from seven years playing the lead in Mamma Mia, employing her vocal talents to great effect narrating High Wages. It was an absolute treat. I wandered round the house, drove to collect friends from the station, and spent hours weeding the garden, and all the while the tale of Jane Carter, the draper’s assistant turned businesswoman, filled my ears. Entrancing stuff!

The plot is surprisingly simple: the orphaned Jane Carter, working in a small town draper’s store, spots an advert looking for help in a much grander business in the nearest market town (surely meant to be Whipple’s home town of Blackburn?) and from that brave step a career takes off: Jane flourishes at a time when women’s fashions are changing. The pre-World War One middle-class habit of having clothes made up by a ‘little local woman’ (dressmakers in books always seem to be little) from fabric and a pattern bought in a shop, gives way after the War to an explosion in the popularity of the off-the-peg, ready-made dress market, and Jane Carter spots her opportunity. Setting up on her own in business as a young woman would seem an impossible dream, but she has the support and financial backing of the generous Mrs Briggs. Mr Briggs is a partner in one of the largest cotton mills in town, and every week he has been handing out the housekeeping money: Mrs Briggs, a woman with a very humble past, has been so economical with the cash that she has a secret nest egg and is more than happy to lend it to Jane.

On the surface, this is a novel about fashion, and also there is a gripping love story, an affair with a married man that I think must have slightly shocked some of Whipple’s 1930 readers, and might explain why she had to find a new home for the book when her first publisher rejected it. But actually it is about the importance to women of money: Jane Carter has no money of her own, which ties her to her job at Chadwicks, despite appalling hours, inadequate food, humiliation and bullying. Mrs Briggs has money but is keeping it secret. When Jane’s dress shop starts to make money, lots of it, Jane for the first time has the confidence to live her own life, travel as she wishes, and eat in the smartest restaurant in town. And when she and her lover plan to escape, Jane has the capital to support herself in a new life. As

writes in the Preface: ‘In a delightful book full of details of clothes and furnishings, bust-bodices and gloves, Dorothy Whipple creates a powerful argument for the need for women to work, not for political or primary economic reasons, but for self-fulfilment and for the realisation of talent and potential.’Reading Jane Carter’s story has made me think again about the Labour women I am currently studying, and the importance of money, or lack of it, in their lives. And here I am using ‘money’ as a shorthand for the independence they did, or did not have, once they married. For most women born in the early years of the twentieth century, starting a family meant an end to any career, and unless they had money of their own, it meant becoming financially dependent on their husbands. Don’t forget that married women still needed their husband’s permission to open a bank account until 1975 (and I have just been reminded by my Googling that pubs could refuse to serve women at the bar right up until 1982!). My father gave my mother her housekeeping money every week: she had stopped working in 1945 when my brother was born. I still remember her delight when her old age pension began: she opened a building society account and enjoyed telling me the things she had bought ‘with her own money’. This was the norm across the country.

For the women who had struggled to obtain an equal education and to start a career, the loss of financial independence as a result of starting a family was heartbreaking. Surely it underlies Jennifer Jenkins’ passionate plea to her new husband Roy to be supported in her career. ‘You know well that I am not the kind of person who would be satisfied with housekeeping and cooking. You should also know that it is very difficult for a woman (merely because she is a woman) to get an interesting job. …You also knew that before we were married. If you didn’t like it you should have said.’ Even when Jennifer gave up her fascinating job at Michael Young’s Political and Economic Planning think-tank to start a family, she continued to deliver evening classes - probably she and Roy would have called it ‘her pin money’. Edna Healey did the same; after her teaching career came to an end because she had a baby, she began to ‘give talks’. Here are some notes I made from an interview she gave in 1982:

The interviewer moves swiftly on to marriage and children, but is interrupted firmly by Edna – ‘I taught first, for seven years’, she wants it made clear. Now she begins to talk about her life as an MP’s wife with small children, and it is clear that the resentment still lingers. She considers that she was effectively a one-parent family. She says that she tried to think of life as being lived in stages: ‘I became keen on gardening… I knew I had to wash the nappies and be up at night with children cutting teeth, but it was a phase that would pass.’ She says it wasn’t so much that it was hard, but that it was boring: ‘your brain turns to mushy peas’, and you really resent it. Wives and mothers, when they are only that, become invisible, she says, even your children and husband stop noticing you at the kitchen sink, and ‘You almost begin to wonder if you’re there still.’ And when you do achieve something, they are all shocked and surprised; ‘Good Old Mum!’.

In the 1950s, Edna Healey took off her wedding ring and lectured under her maiden name. By the 1970s, when her children were independent, she was represented by Foyle’s Literary Agency, and in 1978 she published her first biography, of that marvel of the independent businesswoman, Angela Burdett-Coutts. No-one was more surprised than Dennis.

Mary Wilson, who started her family in 1943, had no income or money of her own throughout her husband’s rise to political power. When she published her first book of poetry in 1970, and it became a significant bestseller, she was very proud to be able to say that she had used the proceeds to pay off the mortgage on their holiday home in the Scilly Isles.

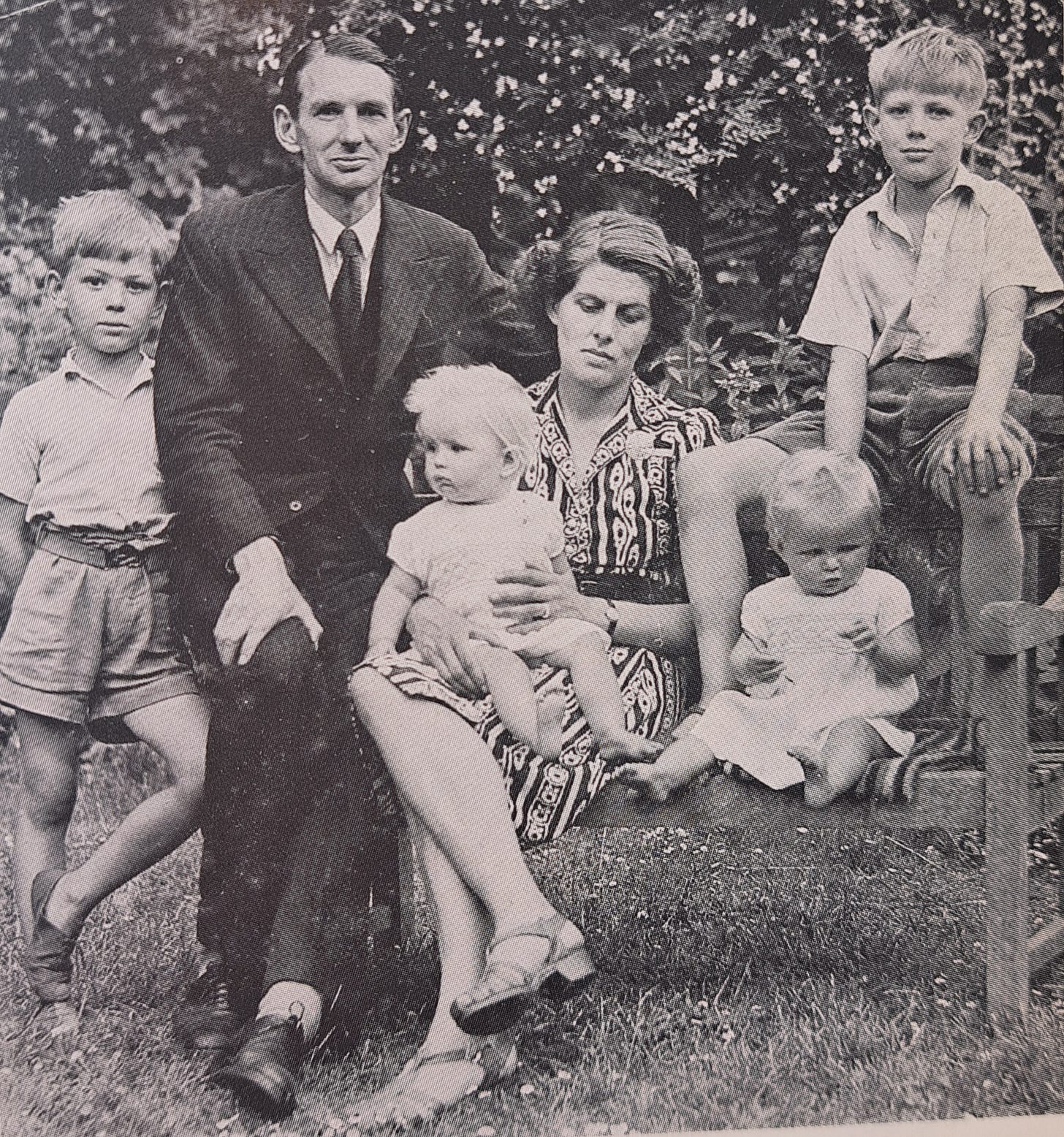

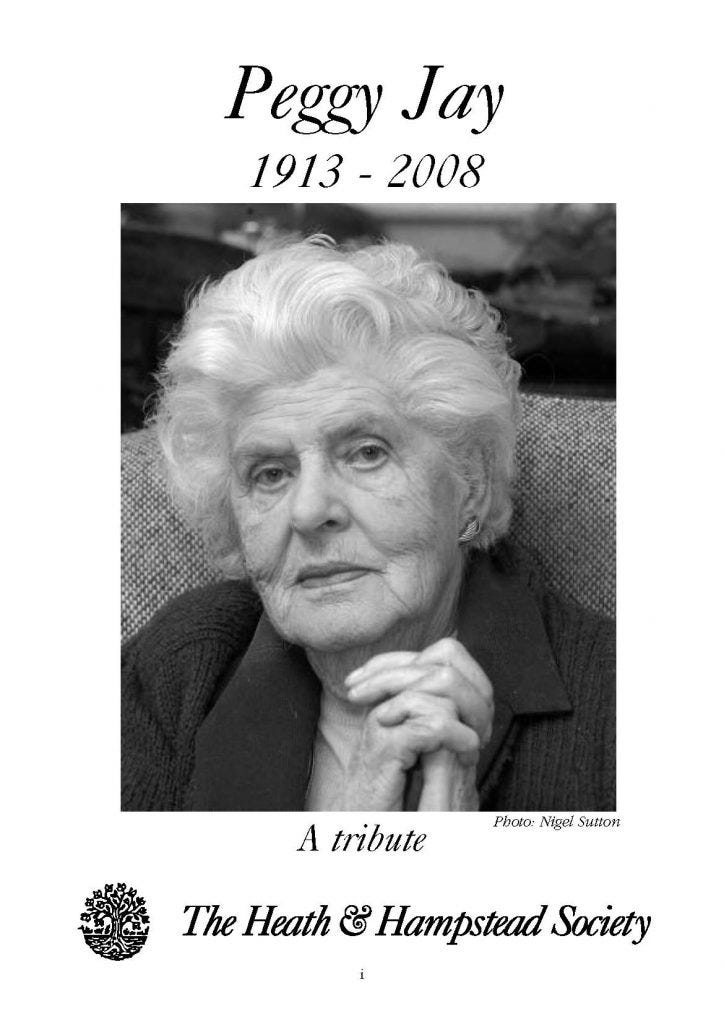

Of course, apart from how it might have made these three women feel, their financial dependence on their husbands was not a practical problem. But this week I have been reading the memoir of another Labour wife from the same generation, Peggy Jay, and it became clear that in an unhappy marriage, it is an appalling problem.

Peggy Garnett was born into a reasonably affluent family in 1913: her mother came from the Palmer of Huntley and Palmer Biscuits fame. Her father, Maxwell Garnett, was an academic who in 1919 was appointed Secretary to the League of Nations Union, and moved his family from grimy Manchester to the leafy suburbs of Hampstead. In the house next door lived the Jay family, including a son, Douglas, six years older than Peggy. As Peggy writes in her memoir, Lives and Labours;

On 28th January 1930 I was seventeen. That evening Douglas brought me a beautiful red and gold edition of Thomas Hardy’s novels. With his wild dark hair and luminous brown eyes he was more than ever an object of intense romantic interest to me. I can remember the exact spot where I saw him in his garden and thinking ‘That man is going to be the father of my children.’

Peggy wrote these words sixty years later: I think it is clear that despite everything, Douglas was the love of her life. Her parents employed Douglas over the summer to tutor Peggy for her Oxford entrance examinations, not always happily: ‘If you can’t learn to spell, it won’t be worthwhile my even trying to get you into Oxford.’ Peggy won her place at Somerville, where she joined the Labour Party and became a committed socialist, only partly because Douglas told her to, as far as I can tell. They became engaged that same year: ‘Here’s ten shillings to buy a ring if you must have one’, he wrote to her. No-one bothered to encourage her to finish her degree: so keen was she to marry Douglas that she left after two years with just a diploma in economics and politics. They were married in Hampstead Parish church in September 1933, but failed to attend their own wedding reception as Douglas said they had a train to catch.

Already finances were an issue. Peggy’s £50 a year allowance from her parents had stopped, and Douglas gave her £2 10 shillings a week for housekeeping, from his salary as a journalist at The Economist. But Peggy never had a paying job.

It simply never occurred to me that I should do anything but voluntary work. No one during all my childhood had ever made a point of mentioning that someone had to earn what was consumed, and Douglas continued to pay the bills while I undertook increasing amounts of voluntary work. With hindsight, I see what strains this put on the marriage, with disastrous results.

Peggy Jay would go on to have an extremely illustrious voluntary career, as well as four children. She relied heavily on parents and parents-in-law for childcare. She was a London County Councillor for Central Hackney from 1938-49, and for North Battersea from 1952-67. From 1944-9 she was a member of the Royal Commission on Population, and from 1955-60 she contributed to the Ingleby Committee on Family Social Services and Children in the Criminal Justice System. These appointments were based on her being what Herbert Morrison called ‘the common sense amateur’, but of course her extensive experience as a local councillor, a magistrate, and on the Parole Board became enormously valuable. She chaired a large mental health hospital board in London, and in a crowning achievement, Barbara Castle appointed her to chair the Committee of Enquiry into Mental Handicap Nursing and Care. The Jay Report was published in 1979, with Castle saying ‘If I hadn’t expected a controversial report, I would not have appointed Peggy Jay.’

Of course, this level of activity put enormous strains on the family.

On one occasion I rushed into the house intent on being home before the girls returned from school, to hear Helen saying on the telephone ‘No, Mummy’s not in. She’s out giving a talk on the importance of mothers being home when their children get back from school.’

The strain was not confined to the children, nor was it solely caused by Peggy’s activities. Douglas was an old-fashioned philanderer. He had always told Peggy that he did not consider sexual fidelity as an important part of marriage, but around the time that Harold Wilson appointed him President of the Board of Trade in the 1964 Labour Government, he began an affair with his secretary Mary that would lead to divorce and his re-marriage. Peggy had been able to turn a blind, if unhappy eye, to previous dalliances, but this was clearly something more serious. Their children had all left home, there was nothing to keep Peggy in a marriage that was making her desperately miserable: except, of course, that she had no money and no income. ‘Ironically, on the day I left County Hall after thirty years’ unpaid work, an attendance allowance of ten pounds a day was introduced, an arrangement which would have transformed my life.’

The divorce, and presumably the wrangling over the alimony that Douglas would have to pay, soured what had been until then a relationship of great mutual respect and friendship. Peggy says that Douglas never really spoke to her again. She moved into the basement flat of what had been the family home in Hampstead, and threw herself into a new project, chairing the Heath and Old Hampstead Society.

Peggy’s memoir ends on a philosophical, but I think rather sad, note:

As fas as my own personal fulfilment is concerned, after years of disapproval from parents and husband, it is only during the last nineteen years when I have been alone, that I have discovered a self that I can like and approve. My childhood problems gave me the driving force for a life’s work. My relationship with Douglas showed me how this work might be achieved. Out of pain my own creativity has grown. My greatest vindication has been the confident optimism with which our children have felt it worthwhile to build homes and families of their own.

In future weeks I will be writing more about the lives of the women behind the Labour Party of the 1960s. Suffice it to say that among its many social reforms, Wilson’s government did a great deal to improve women’s lives, from the Abortion Act and the Family Planning Act, to the Divorce Law Reform Act and the Matrimonial Proceedings Act, the Social Security Act and the Equal Pay Act. Family allowances and widows’ benefits increased. Slowly but surely women would be given more opportunities, and more protection, as they struggled to achieve equality with men in their personal and their professional lives. Jane Carter, with her successful dress shop in Blackburn, would certainly have approved.

All quotations and footnotes are taken from Loves and Labours, by Peggy Jay, published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson in 1990.

I'm totally in awe of Peggy Jay, and never cease to be amazed by the strides made in the last few years for women's rights. A relatively short time in the history of the struggle, (although I'm sure it didn't feel that way for women like Peggy) and so much achieved. I never take it for granted. Another great read.

I thought this a superb piece of writing and loved it. I have still yet to read Dorothy Whipple but can see I am in for a treat! I greatky admired Edna Healey, and found her interview reminded me so much of my mother in law who so resented leaving her librarian job when she married. It is still shocking that it is such recent history. I didn't know of Peggy Jay, but what an extraordinary woman she was.