Dear Mac.

How’s yourself and where’s yourself? My chief reason for writing is, that, as I always told you, I’m going to make your fortune, and you’ll be happy to hear that the feat is almost or at least more than half done. I’ve been and gone and written or got in my head a one vol. novel, a novel for boys, to wit Rugby in Arnold’s time. Ludlow is the only cove besides my wife who has seen a word of it, (and mind if you take it or don’t I can’t afford to have it known) and he thought it would particular do, and urged me to go on with it which I have this vacation and only want the kick on the breech that some cove’s saying he would publish it would give me to finish it. Shall I send you three or four chapters as specimens or will you meet me in town…Do come up and we’ll have a dinner and nox together with baccy and toddy….

Kindest regards to the frater. Ever yours fraternally.

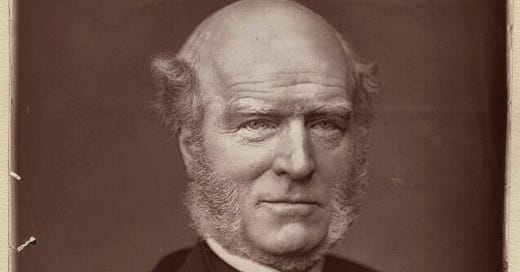

I love this letter: it tells you everything you need to know about its author, Thomas Hughes - I have spent many, many months in the archives of Macmillan & Co, the publishers, and absolutely no-one else in mid-Victorian Britain wrote to Alexander Macmillan in quite that way. Of course, there are other things you might want to know about Hughes, but they are not as much fun, although they are deeply impressive. He was born in 1822, the son of a Berkshire squire of literary tastes, was raised to love the traditions of the countryside, was privately educated at one of the best schools in England, and then studied at Oxford. He was a vigorous sportsman, a particular fan of boxing, as well as a practising barrister, and in appearance rather like a young Mr Pickwick. His literary style might have the flavour of a PG Wodehouse character, even though he predates that miracle of comic writing by some fifty years, but there was much more to him than that: early Christian Socialist, emancipationist, founding influence on both the co-operative and trades union movement, Radical Liberal MP, Utopian colonist, Queen’s Counsel and County Court Judge. But of course, the one thing he will always be remembered for is the book he describes to Macmillan in the letter quoted above: Tom Brown’s School Days.

This recent episode of The Rest is History is an excellent survey of the impact that Tom Brown has had on children’s literature ever since it was published in 1857, and it is easy to trace a path through Billy Bunter’s Greyfriars, and Enid Blyton, all the way to Harry Potter and Hogwarts. Tom Brown has never been out of print, its reach was worldwide (according to Wikipedia, for instance, in Japan, Tom Brown's School Days was probably the most popular textbook of English-language origin during the 1860s until the First World War). It has been filmed five times, and it spawned a highly successful spin-off, the Flashman series by George Macdonald Fraser. Its success was immediate, much to Hughes’ surprise, and it was the single most important title that Macmillan had ever published, propelling them into the big time.

Tom Hughes had not planned to write a bestseller or make his fortune, although he undoubtedly did: his aim was to write a book of the sort that his own children might read, and which would explain to the world the power of a good man to influence a generation: for him, Dr Thomas Arnold, headmaster of Rugby School, was that man. Thomas Arnold had arrived at Rugby in 1829 and over the next thirteen years completely transformed the public school experience in England. Although Arnold was a distinguished scholar, he believed that academic success was less important than moral progress, within a strong Christian faith, and that character was formed through hard work and discipline. ‘It is not necessary that this should be a school for 300 or even 100 boys, but it is necessary that it should be a school of Christian gentlemen.’ By the time Arnold died suddenly in 1842, it was already possible to trace the impact he was having on the British public school system, as ex-pupils and masters from Rugby spread his methods into other establishments. Part Two of this Substack will follow some of their stories.

Arnold’s disciples were determined to keep the flame burning and less than a decade after his death his teachings were being reflected in the Christian Socialist movement, or ‘the Gospel according to FD Maurice’. Some of the early members of this group were John Ludlow and Charles Kingsley, but Ludlow’s best friend was the young barrister Thomas Hughes. Christian Socialism was born in the aftermath of the failed Chartist protests of 1848, and it took just a couple of years for the first concrete expression of their philosophy: that the adult working classes deserved education if democracy was to work. The Working Men’s College was founded in Red Lion Square, London by Maurice, Hughes, Furnivall and other leaders of the movement, and opened its doors in October 1854, with around 130 students enrolled to study humanities (including theology, history and politics), mathematics and natural sciences - all to be taught by volunteers drawn from Maurice’s circle. Tom Hughes, aware that sometimes more might be needed to encourage regular attendance, introduced social evenings of singing and sports, particularly boxing. Charles Kingsley would lecture there, as would Thomas Huxley and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and in a tremendous publicity coup, even John Ruskin. The Macmillan brothers were enthusiastic supporters of the endeavour, with Alexander instrumental in setting up a Cambridge college in the same mould.

Meanwhile, Tom Hughes was pondering how best to celebrate the life of his hero, Dr Arnold, and had come up with an idea for a semi-autobiographical novel aimed at boys. Arthur Stanley, a proud disciple of Arnold and the future Dean of Westminster, had already published a two-volume biography of the headmaster in 1844, which framed his life in mainly spiritual terms, full of Victorian pomposity. Hughes wanted to highlight the effect the man had had on the pupils of Rugby School, but paid homage to Stanley’s efforts by enshrining him within his novel as the saintly little boy, Arthur, whose life and near death have so much effect on the young Tom Brown. This new book was to be written with the express purpose of spreading Arnold’s philosophies more widely across the population, particularly among the young, and so Tom Brown’s School Days was born.

The idea of a novel that would bring Arnold to life delighted the Macmillan brothers, and throughout the autumn of 1856 Daniel exchanged copious notes with Hughes on the subject, all of them extremely complimentary. Raised in an Arran croft, Daniel was the first to admit that he was no expert on life in an English public school, so when Hughes asked him for an opinion, he looked around for someone to help. Luckily in Cambridge there was no shortage of old Rugbeians, and he shared the manuscript with a Mr Mayor of St John’s:

who thinks it very fine indeed and sure to be a hit. He thinks the football business wonderfully done. I feel sure it must be – but as I know nothing of the way you played I cannot get up sufficient interest. Mr Mayor thought the peashooting stories would stand abridging. I am not sure that he is wrong. But of course you must be the ultimate authority on such matters… I cannot trust myself to tell you how much I like the other chapters…if the rest of the book is as good – and a man who could do these things could do anything of the kind he liked – there is no doubt of it being a hit.

Mayor’s other comments were that some of the speeches, especially from Brooke, the head of house whom Tom hero-worships, were ‘too manly’, his sentiments too much like the words of Maurice rather than Dr Arnold. Daniel warned Hughes against becoming too preachy ‘Boys w’d delight in it if care is taken not to let them the least see that you were trying to make them good.’ The truth of this advice went to the core of the book’s popularity. But Hughes was determined not to lose his moral purpose. In a preface to the sixth edition he wrote

Several persons, for whom I have the highest respect, while saying very kind things about the book, have added that the greatest fault of it is ‘too much preaching’; but they hope I shall amend in this matter if I ever write again. Now this I most distinctly decline to do. Why, my whole object in writing at all was to get the chance of preaching! When a man comes to my time of life and has his bread to make, and very little time to spare, is it likely that he will spend almost the whole of his yearly vacation in writing a story just to amuse people? I think not. At any rate, I wouldn’t do so myself…My sole object in writing was to preach to boys: if ever I write again it will be to preach to some other age.

Daniel’s mind was already turning over the promotional possibilities, remembering what they had learned from the experience of Kingsley’s Westward Ho!, their only previous commercial success. His plan was to market Hughes’ book initially into the circulating libraries and Book Clubs in one volume, and then as it became known, to publish a smaller cheaper version suitable for giving to boys as prizes or presents. He proposed an initial print run of 750 copies, enough for the libraries, and then to let it go out of print for a short while, sufficient for there to start a clamour for a second edition. Canny stuff for the mid nineteenth century!

Meanwhile Hughes’ working title, ‘Public School Life’ needed revision. Daniel wrote ‘please invent a title and as good a one as you can. A good deal depends on it. The shorter the better…Tom Brown’s School Life? English School Life? School Life? School Life in England? These are all poor, most likely you have a genius for names.’ Hughes did not need to do much more work on this and ‘Tom Brown’s School Days’ was quickly agreed upon.

Hughes, whose main profession was the law, was a nervous first-time author.

Criticise, cut out, tell me to amplify anywhere...I haven’t the smallest vanity in my composition and don’t care three straws how it’s knocked about…Show it to anybody you please, only don’t give my name, as it might do me harm in this dirty hole, where people fancy you can’t be worth a button if you’ve anything in your head but contradictory statutes and unprincipled decisions.

Again, this was not the usual type of language among Alexander or Daniel’s correspondents, and the freshness and humour was spilling into the novel as he wrote it, much to the brothers’ delight. Hughes himself was showing excerpts to Maurice and to Kingsley and had a full chapter plan and a timetable worked out.

Suddenly all was thrown up in the air – Tom’s children came down with scarlet fever and his eldest daughter Evie fell ill and died in December 1856. The writing ceased, and Ludlow suggested to Alexander that it might be best to find another author to finish it or publish just the fragment. But as Hughes wrote: ‘I was very near giving up the book in disgust, but my wife is against that, and no doubt I should soon repent myself...’. In particular Hughes took comfort from his hero FD Maurice’s teachings, that Death was just a river to cross, and that there was no reason to fear eternal hellfire or damnation, the family would all be reunited on the other side.

By January 1857 the Macmillans began typesetting and editing the work, perhaps keen to ensure that Hughes did not stop writing. Concerned that news of the project would leak out around the London market, they wanted it to be printed in Cambridge, and they needed the language to be modified. In February Hughes had to agree to let the ‘damns’ be taken out. He wrote to the brothers:

I can’t remember above two altogether. Only mind, boys then swore abominably: I did myself til I was in the fifth, I daresay they do still. Besides, if mamas won’t buy for young hopefuls, young hopefuls will for themselves…. But when you tell me that you have altered ‘beastly’ into ‘inhumanly’ drunk, I suppose I think really that it’s time for me to give up in despair. However, my name’s Easy: please yourself gentlemen, and you’ll please me.

The Dr Arnold shown in Tom Brown’s School Days is a simplified version of the more complex original: Hughes was determined to make clear the impact the headmaster had on his pupils, the archetype of the wise but strong leader of men that the country needed. But if his Arnold was a simplified, hallowed version, Tom Brown is undoubtedly based on the real Tom Hughes with all his enthusiasms, and the Rugby School of the book is the place that formed the man. Both Toms come from typical English country gentry stock, where hunting, shooting, bird-nesting and fishing are the main entertainments, and where the father’s one care is that the school he chooses will produce a ‘brave, helpful, truth-telling Englishman, and a gentleman, and a Christian…That’s all I want.’

As soon as Tom passes through the gates he begins to be proud of being a Rugby boy: as soon as he has heard Arnold preach, he resolves ‘to stand by and follow the Doctor’. Much of the early part of the book is taken up with football and boxing matches, but gradually Tom faces a moral struggle – should he cheat in his homework as many boys do, or follow the example of the saintly Arthur, based on Dean Stanley, and make the ethical choice of honest hard work and occasional failure. Pleasing Dr Arnold means being honest, and gradually Tom realises that this is a parable for the Christian life.

Where Tom Hughes’s view of Rugby School diverges from the sermons of Dean Stanley is in the importance he places on team sports. Hughes was never an academic, but he was the captain of his house cricket and football teams, and his passion for sport, and his belief in the value of team games shines through the book and makes it fun for a child to read. Tom says that cricket ‘merges the individual in the eleven, he doesn’t play that he may win but that his side may’. Dr Arnold had not been opposed to physical exercise, he understood that team spirit could be created on the playing field, but to Hughes it was more than that, almost part of religion itself. When Stanley, a less sporty individual, read Tom Hughes’ book, he wrote that it was ‘an absolute revelation…a world of which, though so near to me, I was utterly ignorant.’

Tom Brown’s School Days was first published on 24th April 1857, with a second edition in July, a third in September, a fourth in October and a fifth in November. Initially it was Hughes’ intention to publish the work anonymously, but by May he felt that the secret was out – he blamed Kingsley, who had told everyone in their circle. By August, with the book already into second edition, he was writing ‘What an easy fool the public is! Had I known it sooner I would certainly have plucked the old goose to some tune before this.’ By January 1859, 11,000 copies had been sold, 28,000 copies by the end of 1862. Altogether they would print more than fifty editions in thirty years.

Hughes had initially sold the copyright to Macmillan for a £150 flat sum, but almost at once Alexander offered to renegotiate – at first Hughes resisted, feeling duty bound as a lawyer to stick to his agreement, but under pressure from his friend Ludlow he repented. Thereafter the profits were shared 50:50, and in the first seven months, Hughes received £1,250. Charles Kingsley, who had loved the book from the first, but in rather an envious way, wrote ‘From everyone, from the fine lady on her throne, to the redcoat on his cock-horse and the schoolboy on his form…I have heard but one word, and that is that this is the jolliest book they ever read.’

Tom Brown’s runaway sales were a massive boost to the Macmillans’ business, showing that Westward Ho! had not been a one-off success. In May 1857, Daniel’s wife Fanny gave birth to a little boy named Arthur, possibly named with Tom Brown’s great friend Arthur in mind, and Daniel asked Tom Hughes to stand as godfather. Hughes loved to tease his publishers, revelling in his physical prowess and his skills in sports such as boxing and wrestling, where he felt on firmer ground than in spiritual matters. ‘Dear Macmillan, I shall be glad to be godfather to your boy. I will teach him not only the church catechism set apart for that purpose but also the art of self-defence.’ But ten days after he wrote that letter, Daniel was dead.

Next week I will publish at least one sequel to this story, covering among other things why there is a town in Tennessee called Rugby, what happened to the children of Dr Arnold and Thomas Hughes, and how things did not always go well for the headmasters who tried to take Arnold’s teachings out into other schools. But we will end for now as Tom Brown’s School Days ends: with the young man’s visit to see Arnold’s grave at Rugby School:

Here let us leave him - where better could we leave him than at the altar before which he had first caught a glimpse of the glory of his birthright, and felt the drawing of the bond which links all living souls together in one brotherhood - at the grave beneath the altar of him who had opened his eyes to see that glory, and softened his heart till it could feel that bond?

I loved this, Sarah. Thank you. I look forward to part two!