In 1927 Fenner Brockway, an experienced socialist journalist and campaigner, attended the Independent Labour Party Conference held in Leicester. Here, he wrote:

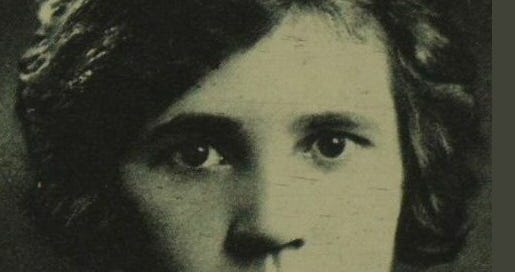

A young dark girl took to the rostrum, a puckish figure with a mop of thick black hair thrown impatiently aside, brown eyes flashing, body and arms moving in rapid gestures, words pouring from her mouth in Scottish accent and vigorous phrases…it was Jennie Lee making her first speech.

Throughout her life, Jennie Lee would be at her most impressive when she was on her feet, speaking without notes, arms flung out, the words cascading from her lips, full of passion. Her career as an MP would stretch, with only one break, from 1928 to 1970. For much of that time she would be best known as the wife of Aneurin Bevan, a towering figure of the Left after the Second World War, and founder of the National Health Service.

But I want to write about the Jennie Lee who, as Minister for the Arts in Harold Wilson’s government in the 1960s, created the blueprint for the Open University and bulldozed it through an unenthusiastic Cabinet and an unhelpful Department of Education to its launch in 1970. I have really enjoyed reading a brilliantly written, prize-winning biography of Lee by Patricia Hollis, written in 1997. If Lee’s life intrigues you, please pick yourself up a copy, from where much of this is taken, as well as her own memoirs.

Jennie Lee was born in Cowdenbeath, a mining village in the Fife coalfields, in 1904, the descendant of a long line of local labour leaders and the founders of Fife’s Independent Labour Party. The family were poor, but that did not prevent Jennie taking full advantage of what the Scottish education system had to offer - in Scotland, every senior school teacher, male or female, had to have a four year degree, a level of pedagogy of which most English state schoolchildren at that time could only dream. In 1922 she went to the University of Edinburgh where she studied a mixture of history, literature, psychology and law - a much broader-based curriculum system than in England, which she would reference when her colleagues were designing the Open University (OU) degree. At some stage she read Albert Mansbridge’s text ‘An Adventure in Working Class Education’, and it would be nice to think that this also had an influence on the creation of the OU, but if Hollis cannot trace a link I’m sure I can’t.

In 1925 Jennie joined her local Labour Club, and rapidly developed a reputation as an assured platform presenter, someone who could be called upon at a moment’s notice to deliver a barnstorming performance, anywhere she could get to by rail. She stuck loyally to the creed of the Independent Labour Party, an organisation that pre-dates the Parliamentary Labour Party. It was differentiated from the Communist Party by its belief in Parliamentary democracy, and unlike the Fabians, it insisted that socialism would be built by empowering the working man and woman, not by ‘seducing the powerful’. Over her career, this devotion to the ILP would bring Jennie into direct conflict with the Labour Party. Nye Bevan attributed this to the Scottish Covenanter stock from which she sprang - even he found it difficult to persuade Jennie to toe any party line. She loved to take the minority view, to be the contrarian.

Jennie’s first career was as a teacher, but she got herself into trouble when she smacked an unruly child, a scandal that the local Communist Party used against her out of all proportion in election propaganda - she never forgave them and her opinion of the Communists was mostly unprintable. She continued to campaign publicly for the ILP, and in 1929 she was selected as a candidate for North Lanark and won a by-election, making her the youngest MP in the House of Commons. She had transformed a Conservative majority of two thousand into a Labour majority of six thousand, and became a national name.

In London she met and fell in love with a fellow Labour MP, Frank Wise. She had already lost her virginity to a handsome young Chinese journalist studying in London; her father had slipped a copy of Marie Stopes’ book Married Love onto her bookshelf in Edinburgh. Another MP, Maude Agnes Hamilton, said of her ‘Almost too pretty, certainly too young!’ She took a flat at 19 Guilford Street, Holborn, next to Ellen Wilkinson, and within their growing social circle she made friends with the Welsh MP, Nye Bevan, and the journalist Michael Foot. Everyone seemed to fall in love with Jennie, and Nye was one of the most heavily-smitten.

Frank Wise was 45, Jennie was 23. He was Cambridge-educated, a career Civil servant, married with four children. Jennie and he never lived together but their flats were close by, and they were known as a couple who went everywhere together, However, Dorothy Wise would not grant Frank a divorce - and this may in fact have suited Jennie, who was nervous of being tied down. Furthermore, in the 1930s it was still the case that a divorce scandal could have ended both their careers. Jennie wrote to Frank ‘Imagine either of us trying to make a speech with any references to the welfare of children or of family happiness…we could easily be painted as depraved homewreckers.’

Meanwhile the Depression was causing untold misery and unemployment throughout Britain. The country turned on the Labour Government for its failure to deal with the consequences, and in the 1931 General Election, which swept so many Labour MPs out of their seats, Jennie lost North Lanark. She would not be an MP again until she won Cannock in 1945. This could have spelt the end of her political career, she could not face going back to teaching, and a career in the law, urged on her by friends, seemed unattractive, However she managed to support herself through journalism and well-paid lecture tours of America and Canada. In 1932 Jennie found herself thrown out of the Labour Party when the ILP, disgusted with what it saw as a betrayal of the working class, disaffiliated. Nye Bevan argued furiously with her that she was backing the wrong horse: ‘The epitaphs of you Scottish dissenters is going to be - pure, but impotent. ..You will not influence the course of British politics by as much as a hair’s breadth.’

Frank Wise was instrumental in the creation of the Socialist League, a ginger group which aimed to push the rump of the Parliamentary Labour Party to the Left and thus differentiate itself from the ‘sell-out’ of Ramsay MacDonald’s National Government. Other members of the League were Douglas and Margaret Cole, RH Tawney, Harold Laski, Stafford Cripps, Barbara Betts and her lover William Mellor, and Jennie of course was involved through Frank. Then out of the blue in 1933, while Frank was spending a weekend with a friend in Northumberland, he had a massive stroke and died. Jennie heard the news from a kindly journalist. She was completely devastated. The worst part was, of course, that she was not the official widow, and had to keep up the pretence that she had only lost a friend. However, Dorothy, Frank’s widow, wrote an extremely generous letter:

My dear Jennie, I do understand how intolerably hard it is for you who have no official ‘right’ to be considered and who have to carry on as if it were only a great friend and not more you have lost…If I had been big enough, I suppose I could have carried on…How one blames oneself now for not always living up to the bigger selfless outlook that I got glimpses of.

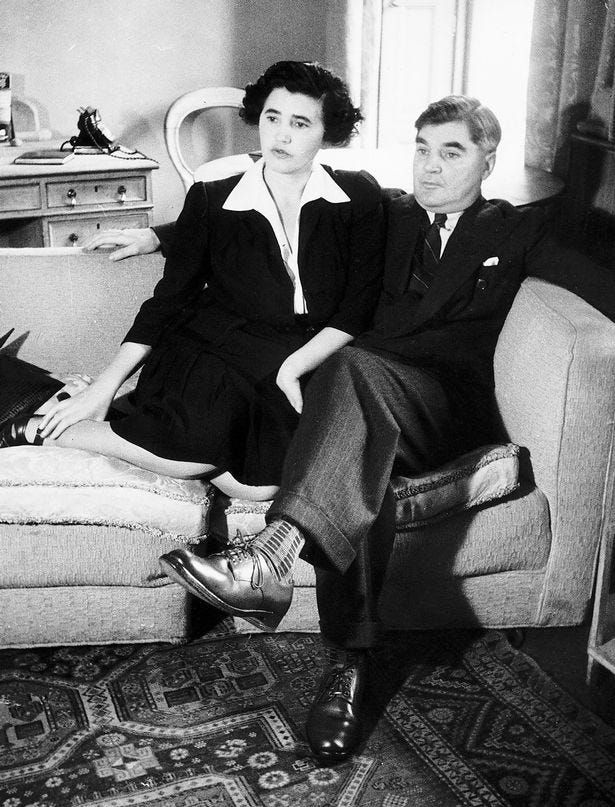

Within a few weeks of Frank’s death, the ever-devoted Nye moved into Jennie’s flat to look after her. In October 1934 they were married at Holborn Register Office, with lunch at The Ivy.

It was an unconventional relationship, and Jennie always said that she had never forgotten her love for Frank. ‘To Nye I was friend and mistress, never wife’. However, theirs became an immensely powerful marriage, a political partnership with a dynamic that changed over time: when Nye first met Jennie she was a national personality, he was just one of fifty MPs from the coalfields. However, over time, particularly during the approach to war and during the war itself, Jennie began to appreciate that Nye had it in him to be a future leader of the Labour party, and one with true socialist beliefs. After his death, she wrote about this to his biographer, Michael Foot:

I had in the course of years more and more accepted that to help sustain Ni’s creative intelligence was much more important than aiming at the dizzy heights of maybe being a second Alice Bacon [Bacon was a junior Labour Minister in the Attlee Government]

Barbara Castle would call Jennie’s passion for her husband ‘Nyedolatry’. In 1945 she wrote a letter to Nye (she called him Ni) which was never sent, in which she wrote ‘It is the woman’s part to give way, to make life smooth, to walk by your side…dreams are reserved for the women who take, not for those who give.’ She was happy to subjugate her own career to his, and was heard to joke ‘My husband is my hobby’. This is not to say that she had no influence: those around Bevan believed that she was essential to keeping Nye on track, when his resolve over crucial matters such as resignations sometimes wavered. Many of his greatest admirers would say that Bevan was a reluctant Bevanite - Jennie certainly was not.

In 1954, seeking privacy and peace, they sold their London house and bought a farm together in the Buckinghamshire countryside, where Bevan loved to play at farming. and this is where they were living when he died from stomach cancer in 1960. Jennie was devastated all over again, and became quite a recluse, to the great distress of her friends and colleagues.

In 1964, Harold Wilson found himself in 10 Downing Street, with a tiny majority, but a lot of ambitions. One of these was a pipe dream he had been considering, something he was calling ‘a University of the Air’. He picked up the telephone to his old friend Jennie Lee:

‘I’ve got a job for you to do - Find a desk and pack your handbag'…

(To be continued)

I'm so glad to read this, as beyond the fact of her marriage to Nye Bevan and her involvement with the OU I knew very little. I love that line : "Bevan was a reluctant Bevanite - Jennie certainly was not." I was so touched by Dorothy Wise's letter. As you say, generous of her.

Very much looking forward to part two!

Amazing woman. I did a degree with the OU and never heard her name mentioned. Michael Young gets all the credit.