Susan and Tony

A love story

First of all, some exciting news…I have a publisher for my ramblings and musings on some wonderful Labour women from the 1960s - and a book to write. So my posts may be less frequent over the next few months, but I will still be here, liking and following and commenting on all my Substack friends, and hopefully bringing you all some news from the front line when time allows. I have to hand in the manuscript before the end of the year, and will be keeping my diary clear for publication in September 2027. Special thanks of course to The History Press, publishers of so many wonderful books, particularly about women…they even have a special page on their website!

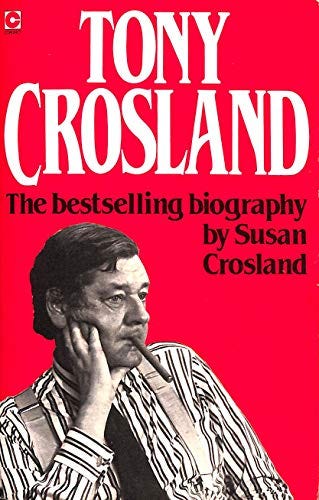

This week’s post is another in a series about the wives of Labour politicians of the 1960s and 70s, Susan Crosland, wife of Tony. Susan was an extremely talented journalist, a well-known feature writer in The Sunday Times for many years. She also wrote a biography of her husband, which I have been re-reading this week. Walking the dog this morning and thinking about it, I realised that what I most wanted to share with you today is not her career, or any impact she may or may not have had on Labour politics in the 1960s. This is a love story, pure and simple, and her book is one of the most intimate portraits of a marriage that I have read, so I am sharing it with you. Be prepared to be moved.

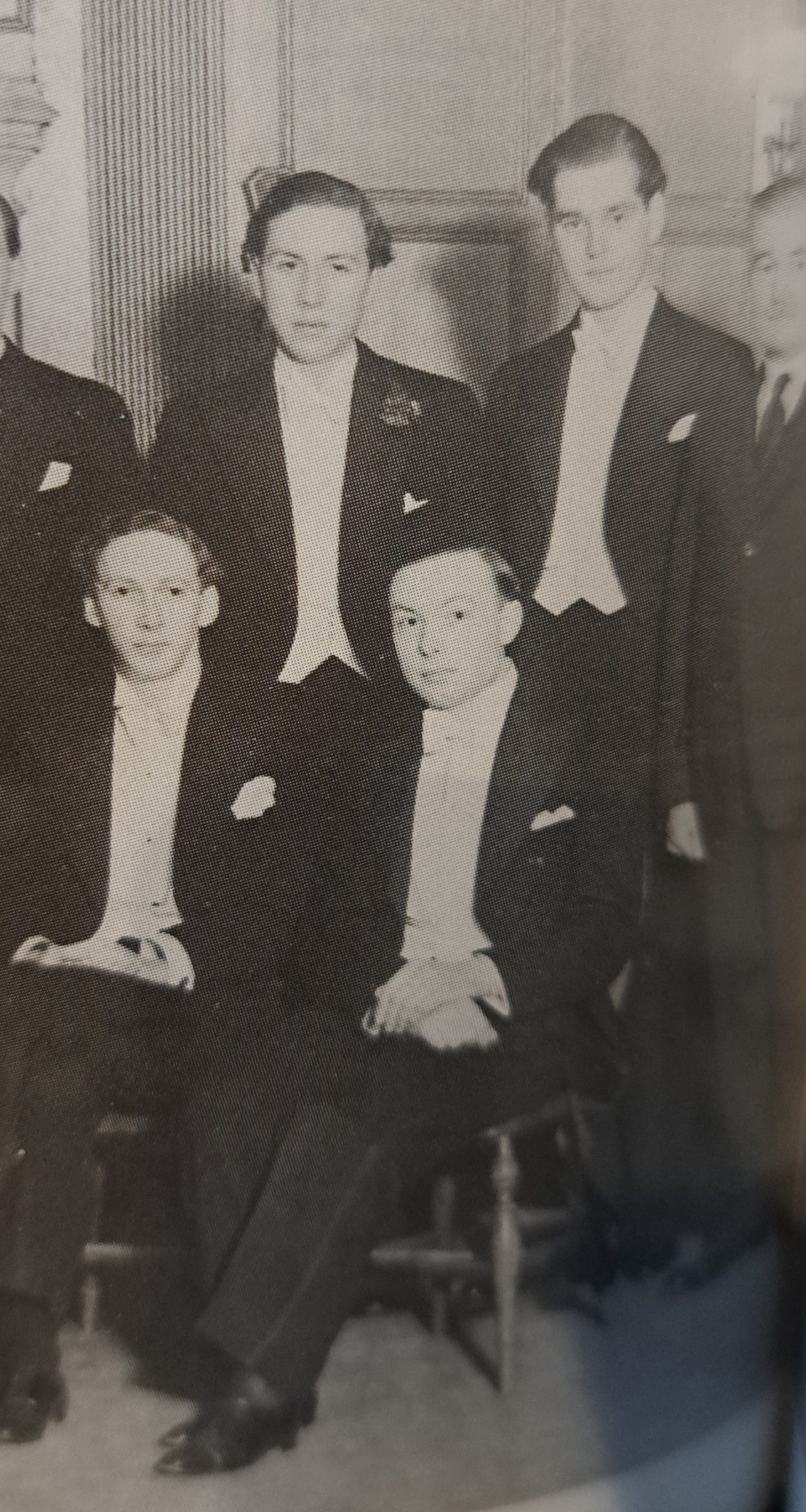

Charles Anthony Raven Crosland was born in 1918, the child of two devout Plymouth Brethren, the same sect that Edmund Gosse wrote so bitterly about in his masterpiece Father and Son. The Crosland family lived in Golders Green, Tony’s father was a high-ranking civil servant, and they were by no means as severe as the Gosses. Yet it had an impact on the young man’s life, if only by sparking the desire to rebel, but perhaps also by breeding in him an intellect prepared to question, and to be suspicious of conformity. In his later life as a politician, no-one could ever accuse Tony Crosland of following the pack. Tony went from Highgate School to Trinity College, Oxford, where he read Classics and joined the Labour Club, coinciding with Denis Healey (at that stage a fervent Communist) and Roy Jenkins, with whom Tony formed a deep and affectionate relationship, which would later descend into jealousy and acrimony.

Remarkably, Susan’s biography of her husband completely disregards the relationship between these two young men, although it is clear from the letters I have read in the Jenkins archive that their relationship had a romantic angle, and may even have been sexual. In A Life at the Centre, Roy Jenkins’ autobiography, he describes Crosland as ‘the most exciting friend of my life’. Crosland, whose own father had died, became very close to Arthur and Hattie Jenkins, Roy’s parents, and as he wrote to Hattie ‘The proof of our friendship was that during the whole period neither of us had any relations at all with members of the opposite sex - we were too wrapped up in our own two interwoven lives.’

Tony was twenty-one when War broke out, and signed up for the Royal Welsh Fusiliers as soon as he finished his exams in 1940. He had a distinguished war record, joining the Parachute Brigade and fighting up through Italy into France in 1943/4. In 1945 he returned to Oxford, took a First in Politics, Philosophy and Economics and became an academic, until in 1950 he was elected as MP for South Gloucestershire. His time in the Commons was short-lived: he lost his seat in 1955 and settled down to write the book for which he is most famous among Labour theorists, The Future of Socialism, published to great acclaim in 1956. Around this time he was introduced, at a party, to a young American woman, Susan Catling.

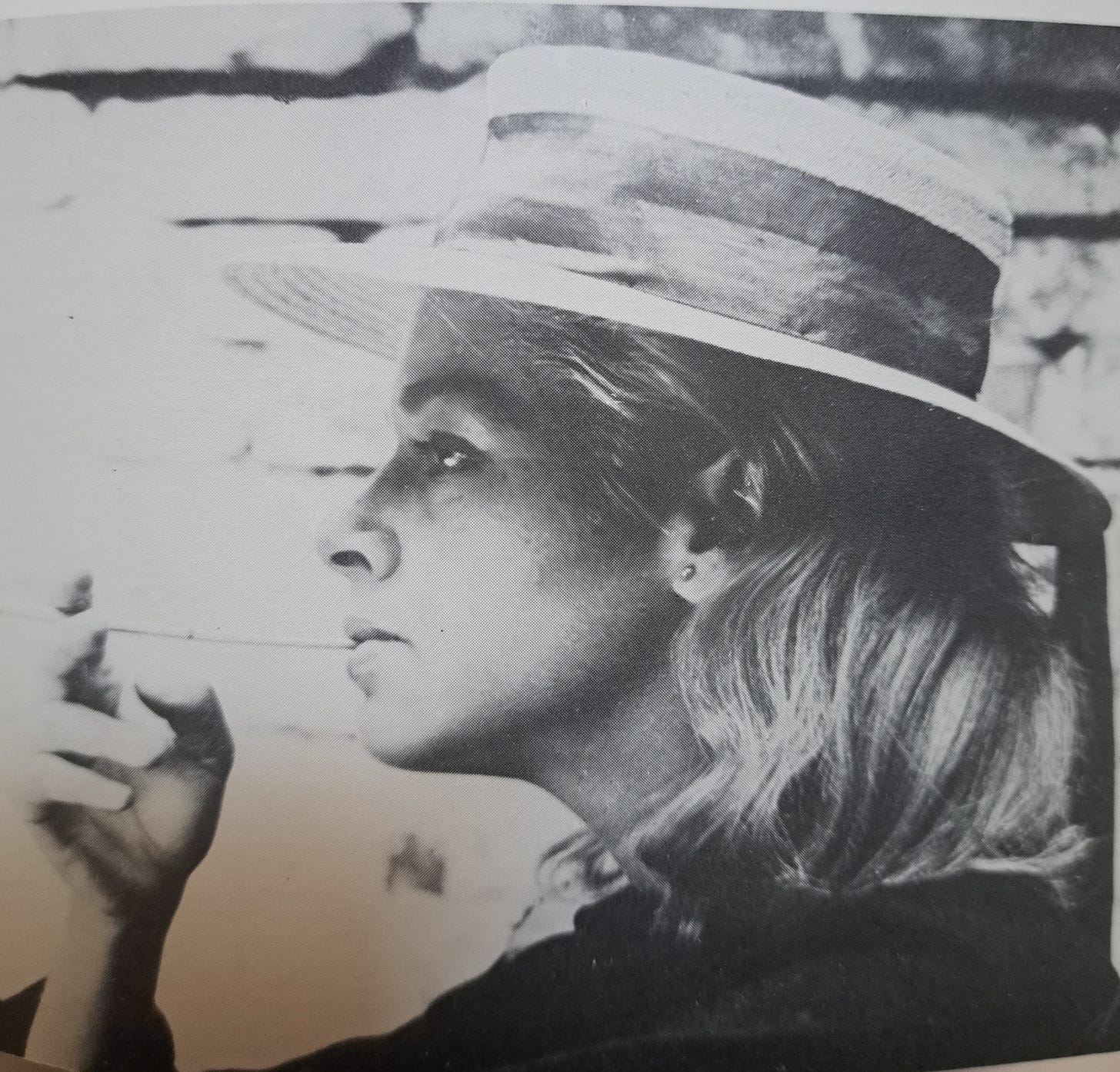

Susan Barnes Watson was born in Baltimore, Pennsylvania in January 1927, the daughter of a family which claimed it could trace ancestry back to the Mayflower. Her father was a journalist, later the Editor of The Baltimore Sun. Susan went to Vassar College in New York State, and got a job teaching at the Baltimore Museum of Art. She married another journalist, Patrick Catling when she was twenty-two and they started a family, producing two daughters, Sheila and Ellen-Craig. In 1956 Patrick was posted to London and Susan, with their flat in Knightsbridge, an expense account, plenty of free time and a live-in mother’s help to keep an eye on the children, began to enjoy a new sort of life - studying in the British Library Reading Room by day, partying in Chelsea with the smart set in the evenings.

Susan was the first to admit she had never heard of either Tony Crosland or The Future of Socialism until the day they met. At the time Tony was finalising a divorce from his first brief marriage, living in a flat in The Boltons, Chelsea, and known as a philanderer and a drinker, unpredictable but totally charming.

Unusually tall, broad-shouldered, to me he looked raffish and was compelling at the same time. I’d never seen irises so pale; I was fascinated by their contrast with the nearly black hair. 19 The Boltons was an oasis. I could scarcely credit it. I still can scarcely credit what happened to my life…He opened my eyes to all manner of concepts, attitudes I’d never analysed, aspects of human nature, pleasure, needs I hadn’t realised before. A whole new education began.

Susan writes that, although no saint, Tony was not interested in adultery: I assume that their sexual affair really only began after Patrick had asked Susan for a divorce in 1960. The couple had been growing apart for some time, and he told his wife he wanted to be free to marry the jazz singer Peggy Lee. Peggy does not seem to have shared this ambition, but eventually the divorce came through in 1964. Tony and Susan may not have been sleeping together, but the intellectual and physical attraction was overwhelming. Within a year of their meeting, he said to her ‘I’m putting my promiscuity aside until you leave England…I want to make the most of this.’

Meanwhile Crosland’s political career was taking off again. In 1959 he was adopted as the Labour candidate for Grimsby, the unfortunately-named fishing port in Lincolnshire. One of their mutual girlfriends, Joanna Kilmartin, suggested to Susan that it might be fun to support him in the General Election campaign, so the two women, neither of whom, we can assume, had ever been anywhere like Grimsby in their lives, set off up north in a yellow convertible sportscar. Naturally the local Labour Party agent was appalled, they were so obviously the Chelsea set, with their chiffon scarves floating. ‘Don’t you go anywhere near that car’, she warned Tony. And when the campaign van he was being driven in broke down, and the yellow convertible was the only option, the agent made Susan and Joanna get out. Crosland won, but only by the narrowest of margins.

In 1960, Susan, now a single mother, got a job writing features at the Sunday Express. When the divorce came through, Susan dyed her hair pink: Tony proposed but she turned him down. All too complicated. She had her own life, two children in local schools; Tony was still racketing around in The Boltons. They tried a separation - but after five days of that Tony called, and said he was coming round for an answer ‘I don’t like these unilateral decisions’.

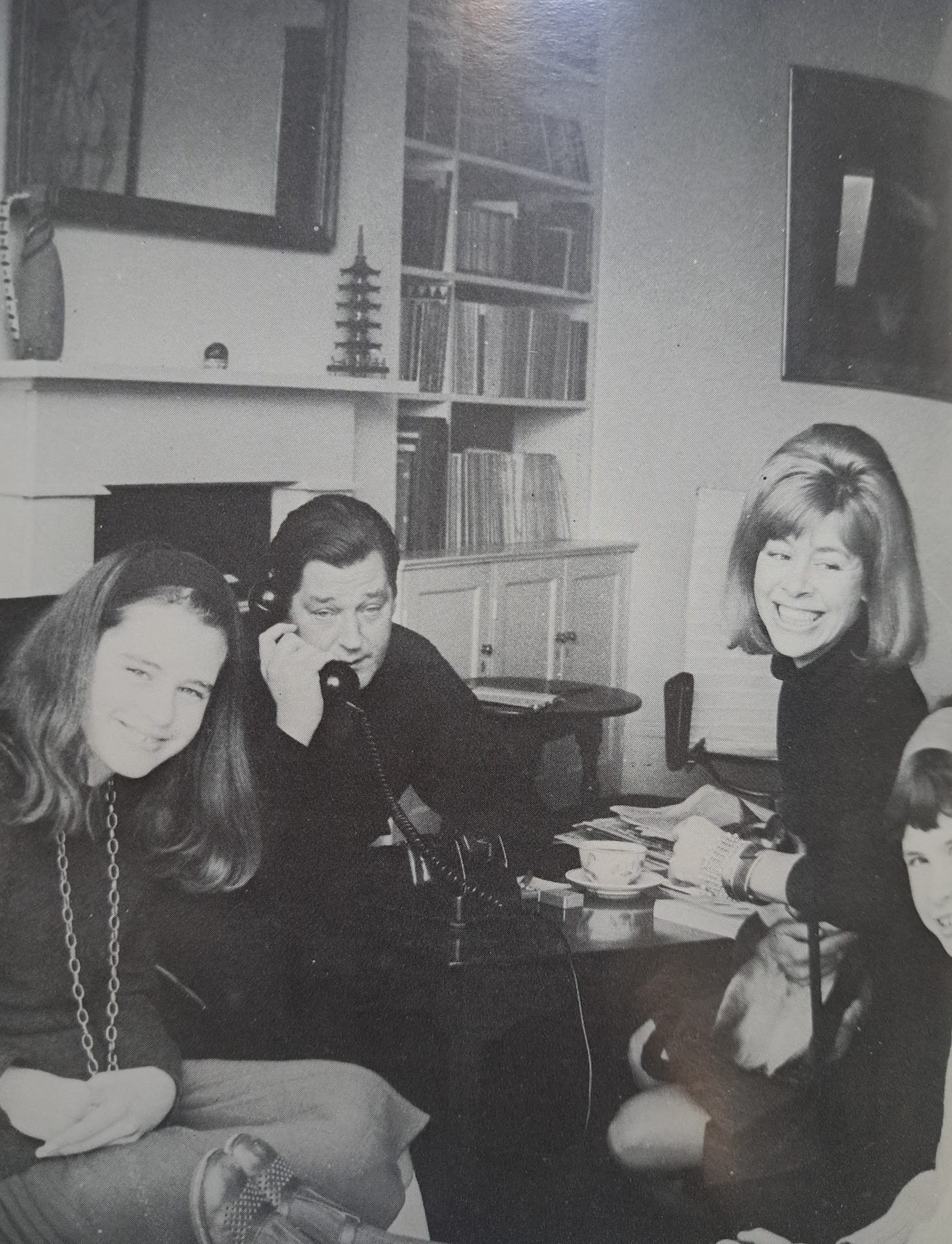

Susan married Tony Crosland at Chelsea Register Office in February 1964. The witnesses were the two widows of Tony’s closest political mentors, Ruth Dalton and Dora Gaitskell. She had offered to let him keep his flat in The Boltons for when he needed to escape - but he only did it once, discovering that a solitary bottle of vermouth in an unheated flat was very unattractive compared to a night with his beautiful, funny American wife and her two lovely daughters. She had also allowed him to negotiate a certain level of sexual freedom - it was the swinging sixties, after all. But she seems pretty certain in her book that he never took advantage of it. Of course, within nine months of their marriage there was a General Election, his majority in Grimsby rose from 101 votes to over 4,000, and from then until the Government fell in 1970 Crosland had a succession of increasingly important political roles, notably as Secretary of State for Education and then President of the Board of Trade. He certainly appreciated the stability of a peaceful home life as he navigated the perilous deeps of the Wilson years.

On their marriage, Susan gave up her job at the right-wing Express, but was quickly taken on by The Sunday Times, where her long-form interviews, often taking several months of work, became a regular feature. The following paragraph is taken from her Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry, written by a close friend of the couple, David Lipsey:

She soon came under the benevolent wing of Harold Evans, the editor of the Sunday Times, using her seductive negotiating skills to achieve remuneration which kept her and her husband in reasonable comfort. Like her second husband Susan Crosland was an impossibly glamorous figure, which could blind people to the fact that she was also, in her own right, an outstanding journalist. She was one of the early practitioners of a genre that later became almost a cliché, the personality profile. Her Sunday Times profiles included a number of sensations and near-sensations: Jeremy Thorpe, the Liberal leader, following the scandal that saw him tried but acquitted for the attempted murder of Norman Scott; Jack Jones, the trade union leader; Lord Hailsham, who nearly became Tory leader; and Kenneth Tynan, the enfant terrible of theatre criticism. Her technique where possible was to quote the trenchant judgements of others to express what she herself thought, giving the appearance of journalistic detachment while at the same time being deadly accurate as to a person’s true character. As with her husband, the glitter of her public persona disguised much hard work. She would research her subjects in immense detail, not just through cuttings but through interviewing their friends (and enemies). Her writing, too, was painstaking, though Tony Crosland was to complain that she always showed her work to him ‘one draft too soon’ .

It was clear to everyone that the marriage was extraordinarily successful, in the way that second marriages can be - both parties knowing what is at stake, being more tolerant, and perhaps having made a better choice than first time around. According to observers, Tony became ‘uxorious, unhappy when away from his wife for long on official business.’ On the wall of his study hung the portrait of Susan he had commissioned - ‘me, standing, wearing high-heeled sandals only.’ Whatever time of day he got back from the office, what he most wanted to do was to talk to Susan. If it was going to be late, she would set an alarm and try to get some sleep, so that she could be awake when he came upstairs.

‘What’s been happening?’ meant my gossip came first while he began to unwind over a drink in his study. Anything good, bad, sad in the children’s day. How my interview had gone. Family news. What else had I done, thought, felt? Once, long before, I’d expressed surprise at his insatiable curiosity about what I did. ‘Never understood the male attitude that your day isn’t at least as interesting as mine,’ he said. If morbidity or depression invaded me, he showed me the way to dispel it…He wanted to tell me about a new concept, or St James’s park at lunchtime…He might ask me to have a look at a passage in a speech if, after redrafting it, he still wasn’t happy…This time of day we had to ourselves was important.

Susan supported him through two separate terms of political office - the 1960s, and again from 1974. This second term saw his career reach the pinnacle of Foreign Secretary, a role which brought increasing strain. It has also to be said that Tony’s individualistic take on socialism made him at different times a hate figure for the Left of the Party, and a great disappointment to the Jenkins social democratic, pro-European faction. He ploughed his own furrow, with Susan always his greatest admirer and supporter. She was not ambitious for herself, often openly joking about the disadvantages of his political career - when his first Cabinet post got him an official driver, she said that at least it gave her sole use of their Sunbeam sports car during the week. When in the 1970s there was a possibility that the Exchequer might come his way, which would have meant moving the family into 11 Downing Street, she told him ‘I don’t want you not to be Chancellor. I just wish it could be postponed for a couple of years.’

The couple scraped together the money to buy a house in Notting Hill, and later, in the 1970s, they also acquired an old mill in Adderbury, near Banbury. That is where Tony was on the Sunday morning in February 1977 when he suffered the massive stroke that killed him. He was only fifty-eight. Susan survived him for thirty-three years, but never remarried. Her biography of him, published in 1982, is agreed to be a wonderful portrait of what it was like to be married to a politician. She makes a good case that a partner’s memory will always be more reliable than the subject’s: ‘Politicians have notoriously bad memories: not so much because they want to adjust the past as because of the continuing surges of activity and emotion and the insecurity endemic to their profession: one moment they are on a pinnacle, the next moment on the ash heap, sometimes rising from the ashes, toppled again.’

Tony Crosland inspires mixed reactions as a politician - to some he is the demon who destroyed the grammar school system in England, to others he is still an inspirational philosopher of the soft or centre Left - quoted just last week by Wes Streeting as one of his ‘lodestars’. When Tony died, the Grimsby agents asked Susan to take his seat, but she declined, saying she lacked either the stamina or temperament. Also, she was finding it hard to leave the house. Austin Mitchell stood as the candidate on the same day that Labour was completely wiped out at Ashfield, but held Grimsby for Labour by the slimmest of majorities. I am going to end this piece the way Susan ends her book. The Times’ leader writer said the by-election result made no sense:

‘Crosland, for all his qualities, was not likely to have been truly accepted by the mass of Grimsby voters as one of their own.’ ‘Sod the patronising buggers’, said one of the by-election workers…He flung The Times to the floor. ‘It’s people like the fancy-pants boys who wrote that - who think they’re so bloody superior - who couldn’t understand Tony. My God it was a pleasure to watch him put them down.’ He started to cry. That being unmanly, he left the crowded office and went down the narrow steep stairs to the door which leads outside.

A great politician. A great journalist. A great love story.

Most photographs and quotations taken from Susan Crosland’s Tony Crosland.

Great news about the publisher Sarah. Well done. It will be an amazing book.

Congratulations and looking forward to reading more profiles of women like Susan!