One Fine Day

A hymn of thanks by Mollie Panter-Downes

‘The long nightmare was over, the land sang its peaceful song’

Everyone told me that I would love One Fine Day, Mollie Panter-Downes’ most famous novel, and how right you all were! It is a glorious celebration of how it felt to be English in 1946, even though people had died, rationing persisted, and the long-established class structures of British society were being shaken as never before.

The day promised to be hot.

Thus opens this simple narrative, one day in the life of the Marshall family, who live in a pretty English village, Wealding, on the Sussex Downs, within easy reach of the sea. Stephen Marshall had fought in the War but now is home, rebuilding his career as ‘something in the City’, catching the 8.47 train with all the other bowler-hatted commuters. We do not hear anything more about his time in service: we know that for his little daughter Victoria, living alone with her mother and spending time with other single-parent families had been fun, free from the usual routines. And we see a single image of his safe return, his wife Laura meeting him at the station and bursting into tears: ‘the spectacle of one more soldier and one more weeping woman.’ But now, in 1946, the initial euphoria of the victory is over, and life seems harder than ever, with new strains tearing at the fabric of their marriage.

The story is mostly told from Laura’s point of view, as she sees Victoria off on the bus to school, and clears up the breakfast things, waiting for the arrival of the rather comical charlady, Mrs Prout. Even the combined efforts of Mrs Prout and Laura are failing to keep up with a house in slow decline. Stephen misses the presence of Ethel and Violet, the pretty little parlourmaids in their neat uniforms whisking away the tea things, long gone to work in an armament factory, and never planning any return to domestic service. For this is a principal message of the book: nothing will ever be again as it was before the War for the genteel, wealthy middle-classes - the sources of their financial comfort are as threatened as the British Empire they had helped to build, the staff who made their lives so easy have vanished - some to better ways of earning a living, some, like the Marshalls’ gardener, ‘dead in Holland.’

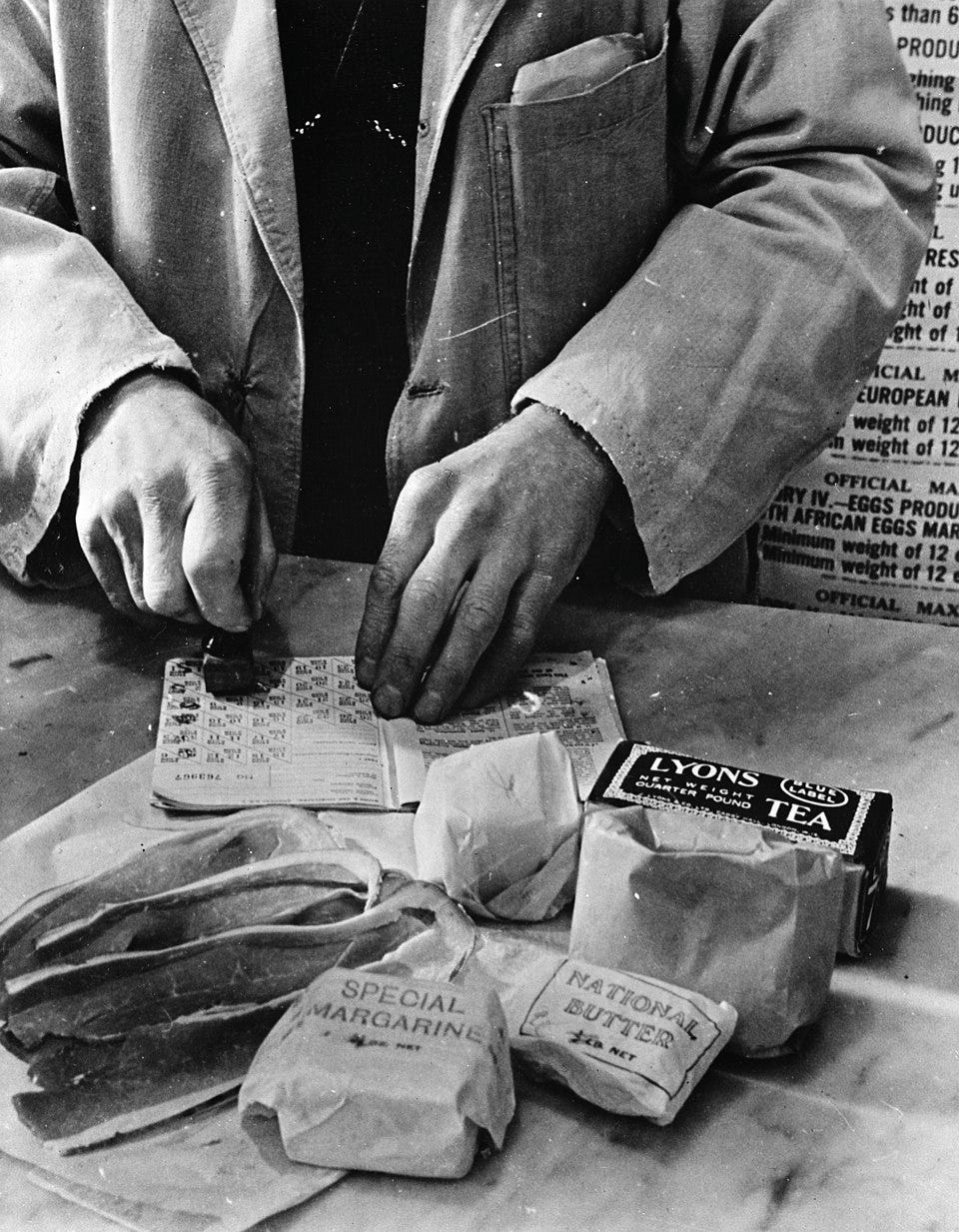

Laura passes the morning travelling by bus into the little town of Bridbury brandishing her ration books, queueing up for the limited supplies in the shops. Rationing would continue in Britain for a decade after the War ended, and in some cases becoming even more restricted - bread was rationed for the first time in 1946. If Laura doesn’t get there until after 11 in the morning, she will find very slim pickings remaining, as if a host of locusts had swept through the town.

This deprivation was slowly wearing Laura down.

Eating had become just that - biting and swallowing. She had never been a greedy woman, but toothsome ghosts of food kept on floating back from the past…some delicious little rum-flavoured cakes which she and Stephen had eaten somewhere abroad on their honeymoon.

Rationing of sweets seemed particularly cruel; Laura’s father ‘hid his sweet ration in a tin in the brown snuggery, retired and ate with private greed behind The Times after lunch.’ This sentence made me smile - I thought of the legends of my dear grandfather, who could never decide whether to divide his ration into 30 days to last the month, or to buy something delicious and eat it all in one glorious feast. My poor grandmother, so the legend goes, was so fed up with finding her ration had been appropriated, that she took to buying liquorice Pontefract Cakes, as the only sweets Herbert did not like. Sadly, so the story goes, she did not like them very much either.

Back at home, Laura sets out on her bicycle on a double mission: to see if she can find another gardener, and to rescue her dog Stuffy, who has run off to join the gypsy pack on the nearby hill. Her first port of call is the ramshackle cottage belonging to the disreputable, scandalous Porter family. Laura has lost track of all the offspring of Mrs Porter, who in her own way had had a very good war, constantly wooed by passing soldiers, to the apparent lack of any interest from Mr Porter. ‘Between bouts in the bracken, Mrs Porter always had a child in her arms, and she loved them all…she enjoyed life, she took what came.’ One of her daughters had joined the WAAF, but returned pregnant by a (married) Polish airman. Her eldest son George comes to the door to talk to Laura - a glorious specimen of young manhood, as Laura notices, but he hardly notices her. Here Panter-Downes shows herself well aware of the invisibility of the older woman, so often remarked on in today’s journalism:

He looked at her amiably, as though she were a nice sofa. That must be the penalty of grey hair…Young men looked at you as though you were a nice sofa, an article of furniture which they would never be desirous of acquiring.

Failing to tempt George into gardening, Laura sets off again, passing the gates of the manor house, lived in for generations by the Cranmer family, but now too expensive a proposition for any family - Mrs Prout has heard that it is to be handed over to ‘The National Trussed.’ Laura visits for tea, watching the family packing up, gazing at the family portraits lining the walls, soon to be dismantled:

The same strong family face repeated itself again and again along the faded red damask walls, blue-eyed, straight-nosed, blooming with the physical beauty that comes from generations of little thinking and much strenuous outdoor exercise.

Such a perfect description of so many old English minor aristocratic families.

During the War, as a perfect example of that enforced communality across the classes, the Cranmer women had hosted circles of village women of all classes sewing and knitting for the troops.

There was something soothing about it, Laura always felt, as though they were repeating some classic pattern which went on recurring for ever in different fancy dresses, the group of women sitting sewing round the lady of the house while their men were at the wars, fighting the Trojans or the Turks or the Nazis. Men must fight and women must sew - of course in this war women had fought too. They had flown aeroplanes, they had been bombed on gun sites, they had struggled in the dreadful equality of icy water among drowning men…There was something soothing about it, the ritual gesture which said, While you destroy, we build up, we stitch and fold quietly in the inner courtyard which is the true centre of the house.

The story ends with Laura recovering Stuffy, shedding tears of relief that the war is over as she and her dog tramp up the hill to get a last view of the sea, before she returns home vowing to start life anew: ‘She had had to lose a dog and climb a hill, a year later, to realise what it would have meant if England had lost.’

So far, so very simple. Nothing happens. Panter-Downes has created for Laura a little odyssey, from country village to country town, from fecund farmworkers’ cottages to the rundown, sterile home of the landed gentry whose days are numbered. What makes this book so powerful, and still so popular eighty years later?

The answer, surely, is the author’s prose. Her descriptions of the countryside are delicious, fragrant, full of ‘flower-and-hedgelore’ rarely found today outside the specialist text:

In spring, dog violets spilled small blue lakes in the bleached grass, followed later by the pink and white restharrow, clean as sprigged chintz, and the great golden candlesticks of mulleins. Up here, on the empty hill-top, something said I am England, I will remain…I will stand when you are dust.

and

The county was tumbled out before her like the contents of a lady’s workbox, spools of green and silver and pale yellow, ribbed squares of brown stuff, a thread of crimson, a stab of silver, a round polished gleam of mother of pearl.

It is beautiful writing.

Panter-Downes can also make me laugh, and Laura’s conversations with her permanently disappointed mother, pining for the Raj in retirement in a small Cornish village are timeless: why on earth had Laura married disappointing Stephen (in trade?) when she had Philip Drayton KC at her feet? and look where it had got her: ‘You spend the entire day doing the work of an unpaid domestic servant. When I think of how you were brought up…’

But I want to leave you with one perfect sentence, that stopped me in my tracks. I would give a great deal to write prose like this:

The yellow roses in the bowl shed half a rose in a sudden soft, fat slump on the polished wood.

For another piece about the impact on the classes of WW2, try:

Phew, she is good isn't she? And really funny in places. Going to look for this one, thanks Sarah.

Wonderful book - her writing is fabulous - and your writing brought it all back so vividly. Thank you!