Mrs Miniver and the class divide

How Britain really was in the 1940s and how it liked to be seen?

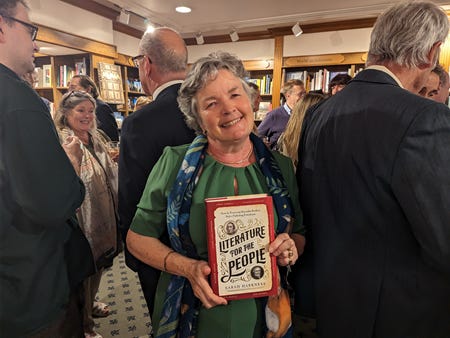

First of all, two little apologies: I missed a week of Substack because I was busy LAUNCHING MY BOOK! Literature for the People is now out in the wild: on Sunday I was talking at the Fowey Festival in the loveliest weather Cornwall can provide, and on Tuesday I was at one of the nicest parties I’ve ever been to, in Hatchards, Piccadilly celebrating, along with a lot of my family and quite a few Macmillans, second and third cousins who had never met before, all introducing themselves and buying lots of copies of the book as presents. I think Macmillan family Christmases will be a laugh this year, as they discover they’ve all given each other the same thing….

My second apology is one in advance, to all the lovely new subscribers who have joined me because my Substack has been recommended by

, one of my favourite authors…if you have joined me for my hot-takes on Arsenal, you may be disappointed…This week I’ve been reading two light, easy novels, all my brain had room for. Although they were very different in subject matter, I have discovered that their authors had much in common, not least that they were almost exact contemporaries, and they both died of cancer in their fifties, thus depriving us of many more wonderful novels and stories they could have produced. Jan Struther, author of Mrs Miniver, was the pen name of Joyce Anstruther, 1901-53. Josephine Tey, author of The Franchise Affair, was really Elizabeth Mackintosh, 1896-1952. The novels themselves were written ten years apart: in fact, Mrs Miniver isn’t really a novel, more a collection of the short diary pieces that Struther wrote for The Times, in the year leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War. The Franchise Affair is a mystery novel, regularly cited as one of the top 100 crime stories of all time.

What very different tastes these two books leave in the mouth.

A little bit of background to the two authors. Both are firmly positioned in the British upper middle classes, with Scottish roots, and both write what they know. Joyce Anstruther took her pen name, an amusing corruption of ‘J. Anstruther’, because her mother Eva was also a well-known writer; her Father was a Scottish Liberal politician. She was married twice, firstly to a Lloyds broker, Anthony Maxtone Graham, the 16th Laird of Culloquhey and 9th Laird of Redgorton (!), and then to a Viennese art historian, Adolf Placzek. She had three children. Mrs Miniver is by far her most famous creation, although I have discovered that she also wrote two of my favourite ever hymns: When a Knight won his spurs, and Lord of All Hopefulness. But don’t write her off as a wishy-washy Anglican, she wrote them as a favour for the editor of Oxford University Press’s Songs of Praise, despite being an agnostic herself - writing to him ‘My dear Percy, don’t tell me you really believe all this stuff.’

Josephine Tey was a more accomplished and recognised novelist, a professional writer, with a series of well-regarded crime novels to her name. Six feature Inspector Grant of Scotland Yard, who also has a walk-on part in The Franchise Affair - his most famous outing being The Daughter of Time, which I read as a teenager and again quite recently - in it, Grant is confined to a hospital bed, from which he quite extraordinarily manages to prove that Richard III could not have killed the Princes in the Tower, it must have been Henry VII. This version of history will run and run, of course, and I have no strong opinion on the matter. Tey’s other famous novel, Brat Farrar, I read just last month, and thought it was really excellent - a young man is persuaded to take the place of a missing heir, with dramatic consequences. If you would like to try Tey, this is the one to start with.

Mrs Miniver I found utterly absorbing, funny and touching. Of course, being diary pieces, she lends herself to being ‘dipped in to’, or she can be consumed in one or two deep breaths, as I discovered, unwilling to put her down. Caroline Miniver is a delightful woman, married to an architect, with three young children (closely modelled on Struther’s own family), a town house in Chelsea and a country cottage near Rye. They are now affluent, with servants and nannies, their oldest boy is at Eton, but Miniver describes how life was more of a struggle when they were first married and before her husband’s career took off. She writes about going shopping, about dinner parties, about bringing up children and about being married. Here she is at a rather awful dinner party:

Clem caught her eye across the table. It seemed to her sometimes that the most important thing about marriage was not a home or children or a remedy against sin, but simply there always being an eye to catch.

Life is becoming increasly more serious, as War approaches. Miniver describes taking the children, the nanny, the cook and the parlourmaid to collect their rubber gas masks in 1938, around the time of the Munich Crisis:

Less than half an hour later they came out again into the sunlit street; but Mrs Miniver felt afterwards that during that half-hour she had said goodbye to something. To the last shreds which lingered in her, perhaps, of the old, false, traditional conception of glory. She carried away with her, as well as a litter of black rubber pigs, a series of detached impressions, like shots in a quick-cut film…Mrs Adie sitting up as straight as a ramrod under the fitter’s hands, betraying no sign of the apprehension which Mrs Miniver knew she must be feeling about her false fringe…

Like all good writers, Struther can take you from the smile to the inward clutch at the heart, as it occurs to her what these masks will mean for the survival of her children: ‘It was for this…that one had boiled the milk for their bottles, and washed their hands before lunch, and not let them eat with a spoon which had been dropped on the floor.’

Mrs Miniver may come from the wealthy classes, but in her warm and appreciative attitude to others, and in her dislike of snobbery and prejudice, she represents the very best of her type. Shortly after the gasmask episode, there is the conversation with the appalling Mrs Burfish about the evacuation of children from London. The Minivers had offered to take six children into their Kent cottage:

‘Wonderful of you,’ said Mrs Burfish, ‘But you know, a small house IS rather different. I mean, one doesn’t expect - does one - to keep up quite the same standards…Of course, I was perfectly civil to the little woman they sent round. In fact, I felt quite sorry for her. I said ‘What an unpleasant job it must be for you, having to worm your way into people’s houses like this.’ But you know, she didn’t seem to mind. I suppose some people aren’t very sensitive.’ ‘No,’ said Mrs Miniver, ‘I suppose not’. ‘And I said to her quite plainly, ‘If there’s a war you’ll find me only too willing to do my duty. But I cannot see the point of tying oneself down publicly beforehand and upsetting the servants.’ She went on ‘And of course, I said to her before she left: ‘Even if the worst does come to the worst, you must make it clear to the authorities that I can only accept Really Nice Children.’ ‘And where’ Mrs Miniver could not restrain herself from asking ‘are the other ones to go?’ ‘There are sure to be camps’, said Mrs Burfish firmly.

It is very satisfying to think that this was printed in The Times, and that, perhaps, Mrs Burfishes everywhere were made ashamed of themselves.

When war broke out, Mrs Miniver took on a surprising life of its own, in the American propaganda machine before Pearl Harbour. Struther embarked on a publicity tour of the States and the book became a massive best-seller, emblematic of the plucky British family facing down the German aggressors. MGM made it into a film which was both a critical and a commercial success, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1942 and winning six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actress (Garson). The most extraordinary thing about the plot of the film is that it bears absolutely no relation to the book - it is set during the war, and contains Spitfire battles, German pilots and little boats going to Dunkirk. But, at a funeral service, it allows the Vicar to deliver the most inspirational exhortation to fight that American filmgoers would ever have heard:

….this is not only a war of soldiers in uniform. It is the war of the people, of all the people. And it must be fought not only on the battlefield, but in the cities and in the villages, in the factories and on the farms, in the home and in the heart of every man, woman, and child who loves freedom. Well, we have buried our dead, but we shall not forget them. Instead, they will inspire us with an unbreakable determination to free ourselves, and those who come after us, from the tyranny and terror that threaten to strike us down. This is the People's War. It is our war. We are the fighters. Fight it, then! Fight it with all that is in us! And may God defend the right.

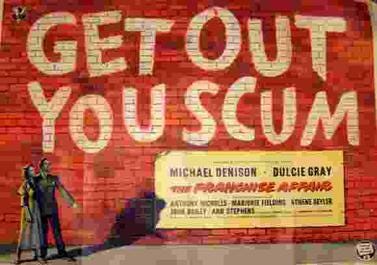

The Franchise Affair is a completely different kettle of fish. Written in the aftermath of the War, it certainly would not have inspired anyone to fight for the British, although the author does not seem to have noticed the fact. It’s not a particularly complex plot: Robert Blair is a solicitor in a county town who becomes embroiled in a mysterious case: a teenage girl turns up half-dressed and covered in bruises, and claims that she has been kept prisoner for a month in a local house, The Franchise, where a mother and daughter, the Sharpes, have tried to compel her to become their servant. As Mrs Burfish knew only too well, it was getting very hard to find good servants in 1940s Britain - but kidnapping them seems a little extreme. There is very little ‘mystery’ to the plot, because both the solicitor and the author nail their colours firmly to the mast: the girl must be lying, because the Sharpes are terribly nice well-bred people, and the girl is working class.

This is not just an attack on the morality of the lower classes, or of young girls, even if they have been orphaned in the Blitz, as this one was. Tey has much to say about the relationship between the ‘red-top’ press, and its readership: easily-led, and easily incited into class violence. ‘Give these Midland morons a good excuse and they’ll witch-hunt with the best. An inbred crowd of degenerates, if you ask me’, says another local lawyer. In no time at all The Franchise, and the Sharpes, are under physical attack, with the local mob roused to a fury by the stories printed in their paper. And Tey singles out women in particular as easily led. Robert Blair, the hero of the tale ‘had had a large experience lately of the woman-in-the-street and had been appalled by the general inability to analyse the simplest statement.’ Thanks, Josephine.

The Sharpe women, mother and daughter, are a strange and forbidding couple, and it is hard to see what Robert Blair finds so enticing about them. I think there is a much better novel trying to get out; one where they are not as innocent as they seem. But even though Tey liked to twist the plot (Brat Farrar is a very attractive anti-hero fraudster) and to muddy the waters of history (Richard III the loving uncle?), she wasn’t brave enough to write this one?

What an interesting post! I find Josephine Tey fascinating. I started my adventure with her with The Daughter of Time and know I will need to reread it more than once. Her writing is layered in ways that I'm constantly surprised by. The Franchise Affair, like The Daughter of Time, was inspired by a story Mackintosh had read -- I believe an 18th- or 19th-century story about a young woman who claimed to have been kidnapped into servitude. I don't know whether the truth of that story was ever established, but the novel, as I read it, goes after tabloid press and the influence it has over popular imagination. Personally, I don't see the prejudice against the poor that many readers see in the story -- I think it's rumor mills, cheap sentimentalism, and the power of sensationalist press that Tey is writing against. I've seen some readers get very upset with Mackintosh for being a Tory. Her political views are certainly interesting in light of her background: she was a daughter of an Inverness shopkeeper who had grown up in desperate poverty. Mackintosh divided her time between London, where she wrote for the theater, and Inverness, where she took care of her widowed father and, I believe, wrote most of her fiction.

Now I need to check out Mrs. Miniver!

I must read Mrs Miniver! The film is a hoot though, but the design is on a completely surreal level - the array of Strawberry Gothic chairs set out for the village gathering, the American style picket fencing - England viewed through the eyes of America, improved where necessary.