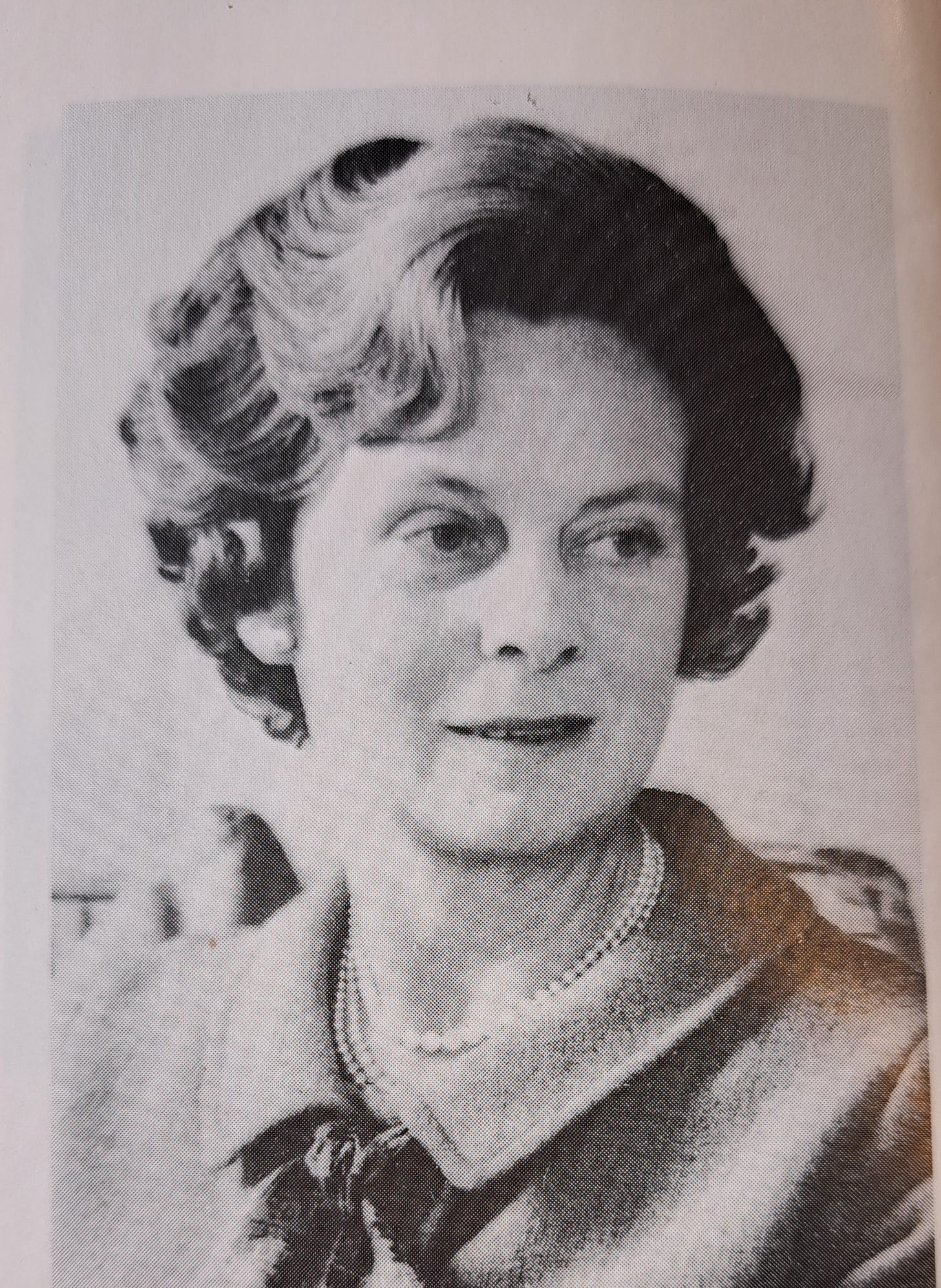

By November 1967, Mary Wilson had been living in the flat above the offices at 10 Downing Street for three years. For a woman who had spent the previous dozen years trying to keep the politicians and the Press away from her front door, it was a particularly cruel situation. Downstairs Marcia Williams, often referred to as Harold Wilson’s ‘political wife’, ruled the roost. And outside the door, the Press delighted in teasing the shy, quiet, Mary. The major culprit was the satirical magazine Private Eye, which once a fortnight published ‘Mrs Wilson’s Diaries’, poking gentle, and sometimes not so gentle, fun at Mary and Harold, at their lifestyle, the food they liked, the way they decorated their flat, and perhaps most hurtful of all, at Mary’s private passion, her poetry. But on 6 November of that year, her life took a turn for the better, when a night at the opera as a guest of Lord Drogheda gave her the chance to fulfil a long term ambition, and meet the poet, John Betjeman.

‘When I saw the guest list with John’s name on it I was very excited, because I had never met him. I had the seating plan changed for dinner in the interval, so that I could sit next to him. We established a rapport straightaway and both wrote to each other the following day.’ This began a friendship that became very important to both of them and lasted until John’s death in 1984.

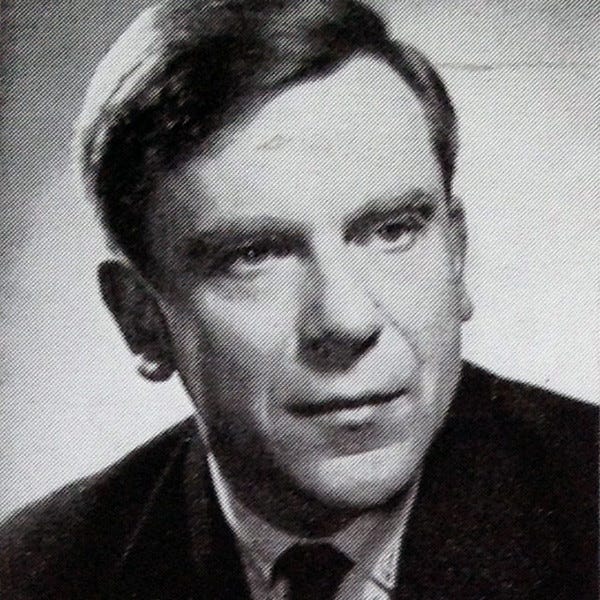

Betjeman was born to a middle class London family in 1906. He was a public schoolboy, educated at Marlborough College, and then went up to Magdalen College Oxford, although he never completed his degree, a fact that he bitterly resented in later life. On leaving Oxford, he chose not to join the family furniture business, preferring to create a career out of his passions for poetry and architecture. 1931 saw the publication of his first book of poetry, and his appointment as assistant editor at The Architectural Review. He soon became a national figure, appearing on radio and then on television, and publishing several very well-regarded collections of poetry. Sales of his Collected Poems in 1958 reached 100,000 copies. He became well-known for his campaigns to preserve Victorian architecture, especially in the years following the Second World War when town planners seemed intent on wiping so many worthy buildings from the urban landscape. It made Betjeman a thorn in the side of the Establishment, and this combined with the popularity of his amusing and accessible poetry meant that earlier in 1967 he had been passed over for the appointment of the Poet Laureate, in favour of the more intellectually acceptable Cecil Day-Lewis.

Mary and John recognised that they had much in common, surprising considering their very different backgrounds and upbringings. On the simplest level, they shared a taste for Victorian poetry: they loved old-fashioned rhythm and rhyme, Wordsworth and Tennyson rather than Eliot and Auden (although John know both the latter two poets on a personal basis). More than that, they recognised in each other a preference for quietude, as they called it, and a dislike of Society and crowds. And they admitted to each other suffering from disabling spells of depression and self-doubt. Their friendship quickly deepened: John would visit Downing Street at teatime and they would talk about poetry and read aloud to each other. There is no doubt that John became enormously important to Mary at a time when she was lonely and depressed, and his encouragement was crucial in her decision to start publishing her own poems. Their letters to each other mostly survive: Mary’s to John are now in an archive in British Columbia, and most of John’s to Mary, which she treasured, were later published by his daughter Candida Lycett-Green as part of Betjeman’s Collected Letters. Candida herself wrote ‘By chance, fame brought him one of the most important and fruitful friendships of his life. Far from the limelight, and completely unconnected to his other worlds, it came at a time when he most needed quietude…Mary’s loyal and completely private friendship was to remain a gentle support to which he knew he could always turn.’

One of the factors in this fascinating friendship is their lack of interest in all the rest of each other’s high profile and busy lives. John had no interest in politics and could not keep up with the ins and outs and squabbles of the Labour Party. If Mary mentioned a name, he would say ‘Is he Left, darling?’ which made her laugh. And she had no desire to mix in his circles. ‘He took me to dinner with John Osborne and Jill Bennett but it didn’t work - I preferred to see him on his own.’ Very early in their friendship he had taken her to dinner at his club, the Garrick, but it had not been a success. He wrote to Mary ‘Never again the Garrick, what a gauntlet of eyes. I never thought it would be like that as I very rarely go there in the evenings. Due apologies.’

After Christmas they planned to walk together, meeting on the bridge in St James’s Park. But it was wet and miserable weather, so they ducked into Westminster Abbey:

We came through the gloomy door /From the cloisters wet with snow /To the Abbey, lit high with candles, / And the Baby asleep below. /A moment of sudden joy /On a dreary winter’s day / Will you remember, I wonder /When the snow has melted away?

I feel like I could play one of those guessing games about the authorship - John or Mary? It’s Mary of course, but I think it’s only the last line that gives it away…Mary’s insecurity about friendships peeping through?

On New Year’s Eve 1967, Mary had appeared in a television interview with Cliff Michelmore, and in the days before VCR, John had not been able to watch, so he asked Mary for the script. His next letter is so genuinely touching:

You are gentle and explicit…it brings out what I knew all along, and that is that you are very clever and a strong character…I want to thank you for existing…I am as certain as I am of stars in the sky that there is a lot of good poetry already written by you and more to be written. Somehow you must be given self-confidence about it. Good poets are always shy of any criticism or even of showing their poetry, for if it is good it is part of themselves, a newborn vulnerable baby when first written and a worn old bore years later but still part of one…I believe in you and so does your family and so do thousands of people. Thank you dear Mary, and go on being kind to the bald old journalist who signs himself yours…

Famously, the two of them took a trip to the town of Mary’s birth, Diss in Norfolk, as they both wrote poems about it which were published together;

Dear Mary, Yes it will be bliss/To go with you by train to Diss, /Your walking shoes upon your feet; / We’ll meet, my sweet, at Liverpool Street./That levellers we may be reckoned/ Perhaps we’d better travel second;/ Or, lest reporters on us burst,/ Perhaps we’d better travel first….

Dear John, Yes it is perfect bliss/ To go with you by train to Diss!…/Now, as we stroll beside the Mere, / Reporters suddenly appear; / You draw a crowd of passers-by/ Whilst I gaze blandly at the sky.

These two poems were not published until 1979, in Mary’s second collection, New Poems. But the trip was something the two friends had planned from the earliest days of the relationship in 1968. Mary anticipated that it might cause a stir. She wrote to John in July of that year ‘I have a feeling, and I’m not usually wrong, that you would rather not embark on the Diss expedition, just with me. I do understand how persecuted one can feel - shall we call it off? I’m quite happy to do so…I can always go another time with a respectable woman companion which would probably be more suitable. I could come to tea with you instead.’ But in the end it was Mary who called it off, not John, pleading an unexpected visit by friends of her son Robin. I think the trip finally took place in 1974, but if anyone knows for sure…?

I believe that Mary shared her love poetry, and the sad story behind it, with John. He wrote ‘Now to come to that poem of yours. It is the best I’ve seen that you have done and that is saying a lot. I cannot fault it. Of course the drive in it comes from the emotion in it. I think you are best as a love poet. It must be maddening that you cannot publish that piece - but I don’t see that if you pre-date it and put it back in 1930 at the bottom - many poets do date their poems, you could not publish it. But what really matters is that you have written it.’

John was already encouraging her to think seriously about publishing a collection of her poems. It was an increasingly difficult time for Mary, in May she wrote that she was ‘feeling very blue for reasons I can’t talk about here.’ That same month she was the guest on Desert Island Discs and remarked that she would ‘endure loneliness very well for a little while’. She was desperate to get to her sanctuary on the Scilly Isles but had to make do with a weekend at Chequers. ‘I’m too dispirited at the moment to take offence - anyone could insult me with impunity. I’ve even got used to being continually mistaken for Barbara Castle at the door of Number 10.’

Robert Lusty of Hutchinson, the publishers, had persuaded Mary to pull a selection of poems together for publication in 1970. But her confidence took a terrible knock when a poem she had submitted to a charity exhibition ‘Wives of Westminster’ was described as doggerel. (The poem in question was The Treasure based on the discovery of a shipwreck off the Scilly Isles). It took a great deal of loving support from Betjeman to keep her going. Then on 18 May 1970 her husband fired the starting gun for the General Election, and Mary was thrown into further panic. How would this effect the publishing project. Even earlier that month, Mary had been asking John for his views. He replied:

My thoughts are these: 1) whether there is an election or not, the politically-minded will say it is electioneering or cashing in on success or failure. 2) Whether you publish now or then, there will be the envious to blame you and pick you to pieces and impute wrong motives. … 6) You will go through agony. You will be parodied, misconstrued, patronised. You would not be a poet if you did not thus suffer. 7) You will have the consolation of seeing yourself in boards and well-printed and produced. That makes up for everything, election or no election, harsh criticism or lavish praise or utter neglect. 8) Don’t bother about reviews. It’s the travellers who sell books, and word of mouth.

In the event, the Labour Party lost the election, but Mary’s poems were published in September 1970, and became an extraordinary bestseller, selling 75,000 copies and paying off the mortgage on their house in the Scillies. Perhaps no-one was more surprised than Mary. She wrote to John ‘Characteristically I feel guilty and ashamed, not elated, because I know I ought not to be. I think the poetry is quite good but it’s ridiculous that it should be a bestseller. Anyway the tumult and the shouting is now over. The reviews were not scathing, but rather kindly and indulgent. ‘There, there, nice little woman.’ Dannie Abse [another of Hutchinson’s poets] summed it up by saying that before he published his next book, he’s going to marry Ted Heath.’

By the summer of 1971, Hutchinson was keen for Mary to produce a second volume, and again she needed John’s encouragement to persevere. He wrote ‘Old fashioned ‘withits’ who regard rhyme and rhythm as fetters and out of date, don’t know the rules you and I set ourselves of ear and metre or stress. So these judgments technically are worthless. It is as though an abstract artist who had never mastered perspective or drawing, accused a representational artist of being no more than a colour photographer….I believe in you, and I say Go ON!’

In 1974, Wilson led the Labour Party into power once more, following the collapse of the Heath Government. This time, however, Mary stood firm: she would not move back into Downing Street, but continued to live in the house they had bought nearby in Lord North Street. She had suffered a terrible loss earlier in the year with the sudden death of her great friend, the Oxford organist John Webster. John had played Gaudeamus Igitur at Mary and Harold’s wedding. ‘I am desolate’, she told John, ‘He was such a dear friend and the only friend who telephoned me regularly just to see if all was well. I shall miss him so very much.’

There were several poems about John Webster in Mary’s second anthology, New Poems, published in 1979.

They telephoned to tell me you were dead -

No ageing years for you, no lasting pain,

And I am glad that you have gone ahead

And I remain

Yet having said this I am desolate;

How could you go away, my dearest friend?

How could you go, and never say goodbye

Before the end?

Of all the evenings when we sat and talked

Nothing remains, no, not one whispered word;

And when I try to recollect your voice

No voice is heard.

How many, many times did beauty soar

Towards the chapel-roof at close of day!

But you have shut the organ-loft at last

And gone your way.

Harold Wilson retired unexpectedly in 1976, although it is likely that he had always promised Mary not to go on much past the age of 60. They retired to a mansion flat in Ashley Gardens, near Victoria, and of course spent many happy holidays in the Scillies. John Betjeman died in 1984. Harold died in 1995, his last years clouded by dementia, but Mary nursed him until the end. He was buried on the island he loved and Mary wrote another beautiful eulogy:

My love you have stumbled slowly

On the quiet way to death

And you lie where the wind blows strongly

With a salty spray on its breath.

For this men of the island bore you

Down paths where the branches meet

And the only sounds were the crunching grind

Of the gravel beneath their feet

And the sighing slide of the ebbing tide

On the beach where the breakers meet.

Mary, now Lady Wilson of Rievaulx, lived on until 2018, reaching the grand old age of 102. On her death, Lance Pierson, Chairman of the Betjeman Society, wrote to the newspapers:

Sir, The death of Mary Wilson prompts the Betjeman Society to ask if it is not time to re-evaluate her poetry and accord it its proper status as good late 20th century poetry. For too long regarded as domestic scribblings, her verse should be looked at afresh by the poetry establishment. It reflects the intensity of feeling and often-powerful description of the commonplace, something she shares with Philip Larkin and her long-time friend John Betjeman. She was President of the Betjeman Society for ten years and we shall always be grateful for her enthusiastic and knowledgeable support.

Mary Wilson is a poet who speaks to everyone who has ever felt lonely, who has battled with depression, who has lost a great love or a great friend, and yet can still take great joy and find beauty in the everyday, in the world around. She wrote about events that moved her: the Aberfan disaster, the Moon landings, the Durham Miners’ Gala. She wrote for her granddaughters, she wrote about her love of the Scilly Isles, she wrote about meeting the Queen and about the atom bomb. And yet she very rarely believed in her own talent. There is no doubt that being the wife of a Prime Minister thrust her into a world in which she was often very unhappy. It is also true that if she had not had such a public profile, she might not have been published at all. She became a heroine to the public, a living demonstration that being married to a man with an important job does not imprison one in the kitchen forever. Private Eye may have tried to make her a figure of fun, but her quiet dignity in public never wavered, whatever the pain it caused her.

I have decided to write no more, as I am not a poet, never was and never shall be. It’s a great relief.

Mary Wilson to John Betjeman, November 1972.

All extracts from poems and letters reproduced by kind permission of the Wilson family.

What a beautiful friendship that gave them both so much. Thank you for sharing their story.

This second part was as fascinating as the first, offering fresh insights on Mrs Wilson and Betjeman. Although it makes absolutely no difference now, I'm glad that she had a trusted confidant who believed in her and her talents. Thank you for posting.