If you thought the first chapter of Gillian Greenwood’s life was intriguing…now read on!

In 1927, at the age of seventeen, Gillian Crawshay-Williams left Chantry Mount School and signed on at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in Holborn, London. For a while she continued to live in St John’s Wood with her foster mother Mim Marillier, but in 1929 she took a bedsitting room in a house in Bayswater, sharing with her friend Margaret Blake, who was two years older. Her brother Rupert had a room in the same house and her father Leslie was in lodgings around the corner. They would all meet for Sunday lunch at a nearby cafe, and Gillian was delighted at how often her father would call to see her. The mystery was explained in 1931 when he married Margaret. More shades of a Rosamond Lehmann novel, it seems to me. Certainly her father was well-attuned to the realities of life for a smart young woman living in London - at the age of nineteen he had sent Gillian to see a well-known gynaecologist to learn about birth control. ‘I think I was the only girl in my set who didn’t have an abortion.’

In 1930, Gillian went to Florence to study etching. As with her other art studies, she would be the first to admit that she could be easily distracted. ‘My professor told me that it was impossible to be in love and study art at the same time. I did quite a bit of etching until I reluctantly gave up my lessons in favour of love. I finally learnt what sex was all about and fell in love with Mingo, a law student.’ It became clear that the affair would never prosper as Mingo’s parents did not approve and her father came to Florence to bring her home. Mingo was later killed in the Mille Miglia motor race. Gillian was one of a very fast, arty set in London, attending all-night parties at the Gargoyle Club where drugs and alcohol were taken to excess - although Gillian never drank. Her friends included Stephen Spender and her cousin Aldous Huxley. She also had a great friend, Bunny, who was gay.

When we were in a taxi on our way to lunch one day, Bunny took out his compact to powder his nose. The driver saw this and when it came to paying he said to Bunny ‘It’s a wonder you don’t wear earrings’. Bunny answered very sharply ‘What, with tweeds?’

In 1932, with no qualifications, Gillian started to look for work. It was the height of the Depression, there were two million unemployed, and she was desperate to take anything she could get. She had learnt to sew at school, and eventually found a job sewing ribbons onto camiknickers at an establishment in Cork Street: it was only when she was asked to start modelling the garments to a room full of men that she realised it was a high class brothel and left. Luckily she managed to get work as a sales girl at Jaeger in Regent Street - and thus began a career with the firm that would last for twenty-six years.

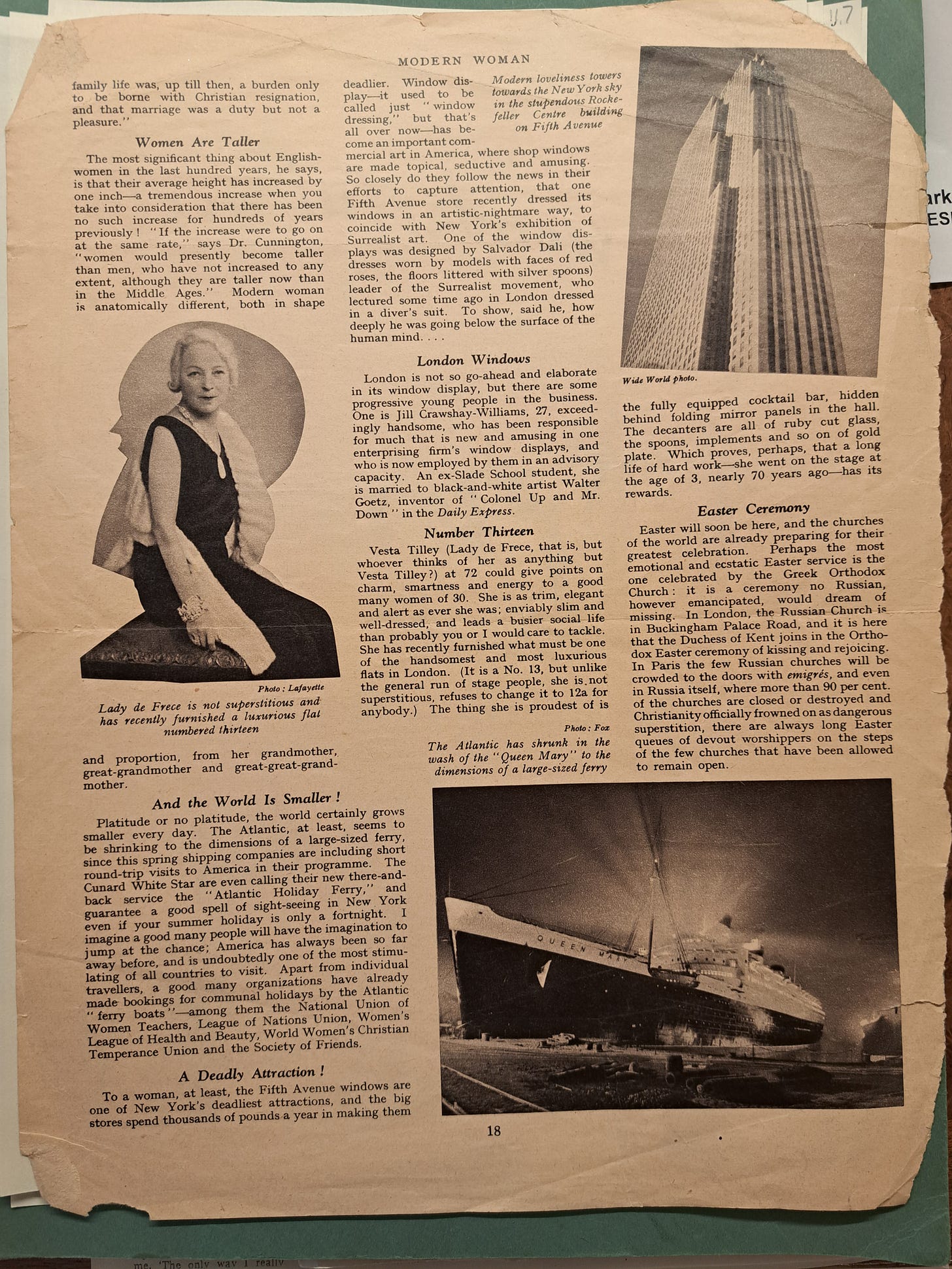

Jaeger had been founded in England in the 1880s by Louis Tomalin, based on research by a German, Dr Gustav Jaeger, into the benefits of wearing wool next to the skin. The brand had notable converts: Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, and many Arctic and Antarctic explorers, including Shackleton, extolled the virtue of woollen undergarments. However, Louis’s grandson Humphrey Tomalin took over the company and in 1930 he hired Maurice Gilbert from Selfridges to relaunch the name as an all-year round high fashion brand. Gillian Crawshay-Williams, with her stylish looks, her artistic background, and her society connections, was in the right place at the right time. She started as a 25 shillings a week salesgirl, dressed in an ugly brown uniform with beige collar and cuffs, which she had to pay for out of her wages. She soon moved into creating window displays with immediate success - her first display of colourful twin sets was a miniature courtroom scene with three tiers of benches, populated with flat cut-out models, each wearing a different colour garment. They sold a hundred sets in four hours.

Gilbert began to send Gillian round the country to the bigger towns where Jaeger had agents in department stores, to dress the windows and to model the clothes at local fashion shows. In 1933 he sent her to Berlin for three weeks to study window dressing, she stayed in a flat with Stephen Spender’s sister. By 1937, she was becoming a famous name in the fashion industry: Crawshay!

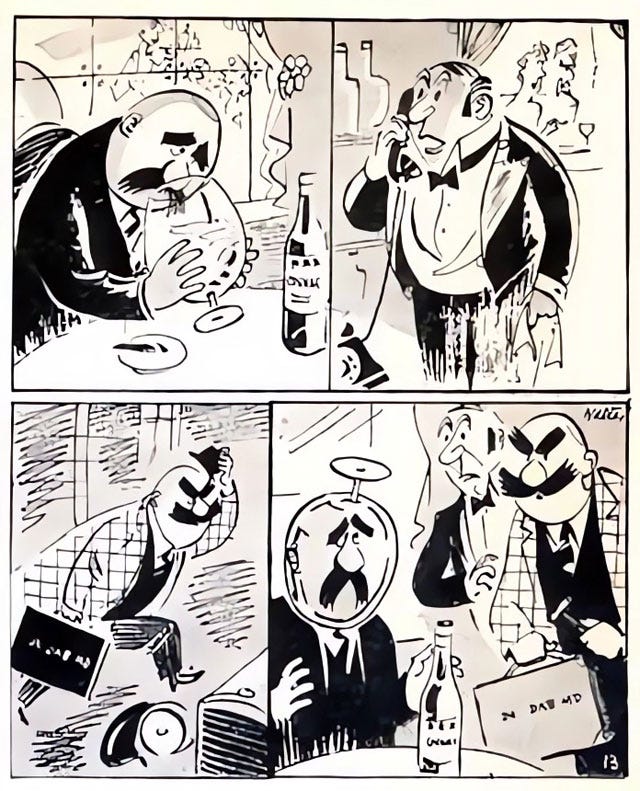

That same year, Gillian married an artist, Walter Goetz, a Jewish refugee from Germany, already famous for his newspaper comic strips ‘Colonel Up and Mr. Down’ and ‘Dab and Flounder’.

But the marriage did not last: the very next year Gillian met and fell in love with Tony Greenwood, the son of Arthur Greenwood, deputy leader of the Labour Party and later to be an MP and Cabinet Minister himself. In among her archives at the Bodleian is one of the saddest letters I have ever read. Gillian has written on it ‘The only love letter Walter ever wrote me: I can’t bear to throw it away.’ It was written the morning after Gillian had left him to return to her parents’ home:

Sweetest

I suppose writing this note in the flat is an unnecessary torture but I had to come here and get something. Tried to ring you twice this morning but by some heavenly foresight couldn’t reach you. Probably that’s as it should be, I’m going to try not to see you. Whether I can go through with this resolution I don’t know. Short of flying the country I hardly trust myself. But in cold blood, if such a thing exists for me at this moment, probably only mutual anguish could come from our meeting, and whereas for me (and you I presume) the pain is hardly any less if we don’t meet, it may at least make it easier for you to know your own mind…[the letter continues for three pages] …If only I could remember something hard or unpleasant about you round which to crystallise some vestige of dislike it would be so much easier. But darling I can’t and never will. I love you.

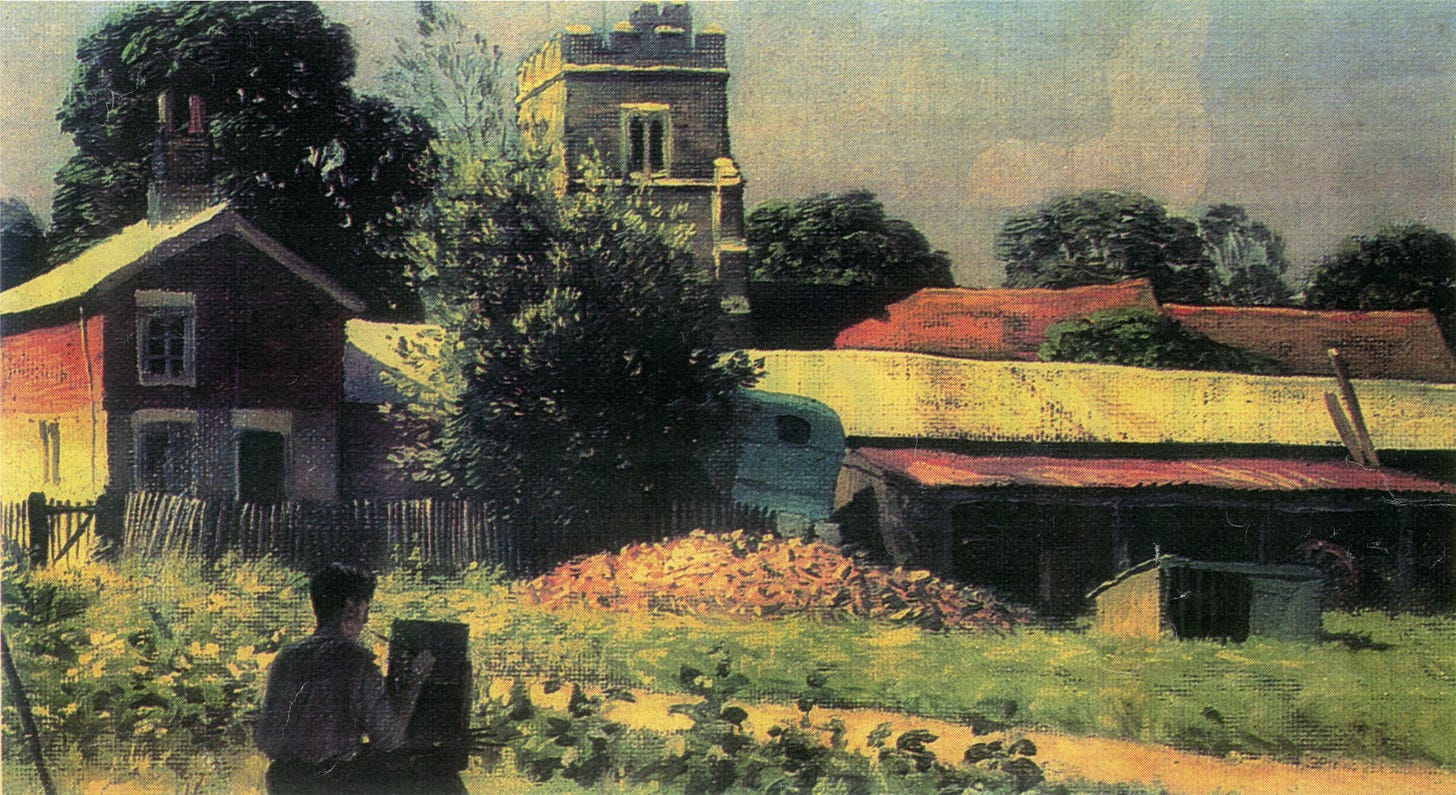

Gillian and Tony Greenwood were married in June 1940, one week after the divorce came through. They took a train to Colchester with a tandem bike in the guard’s van, and pedalled off for a honeymoon on East Mersea, a location they always loved. While they were there, an old friend of Jill’s from art school, Rex Whistler, came to stay and painted the church.

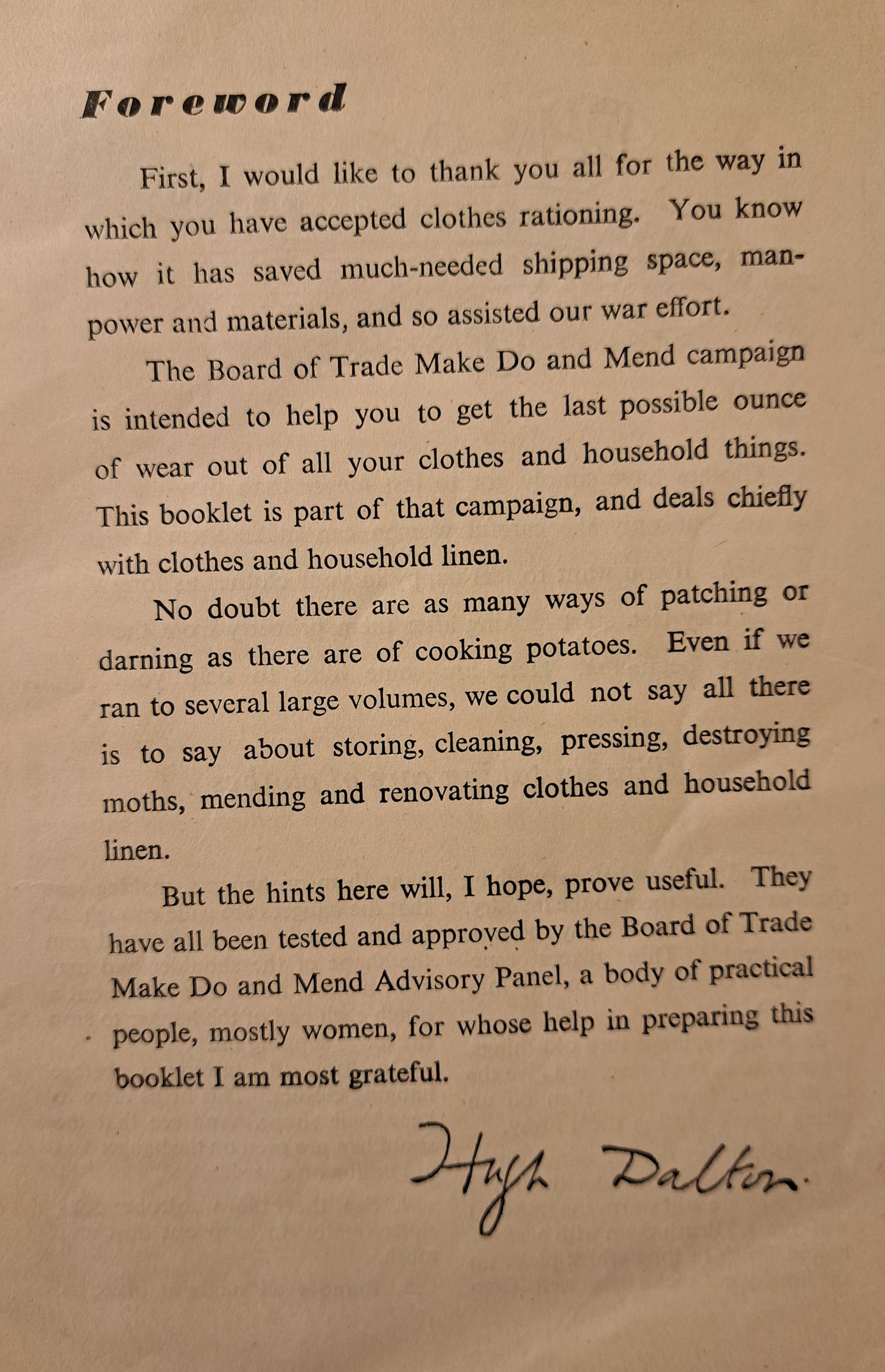

During the war, Jill Greenwood was a press officer at the Board of Trade, and was responsible for writing, or at least editing, this famous pamphlet, Make Do and Mend,

After the War Gillian’s role at Jaeger took her in a new direction - designing street decorations. In 1953 she was given a budget of £34,000 to design the Coronation decorations for Regent Street. As Chair of the Regent Street Association, in 1954, she went on to design the first ever set of Christmas lights for the street. By 1958 she had quit Jaeger to set up a business as a freelance designer, and her biggest ever commission came in 1959 when the Oxford Street traders, jealous of the Regent Street display, gave her the contract for their first ever Christmas lighting display - 43 lamp standards to be disguised as Christmas trees with 2000 yards of glittering holly and candles.

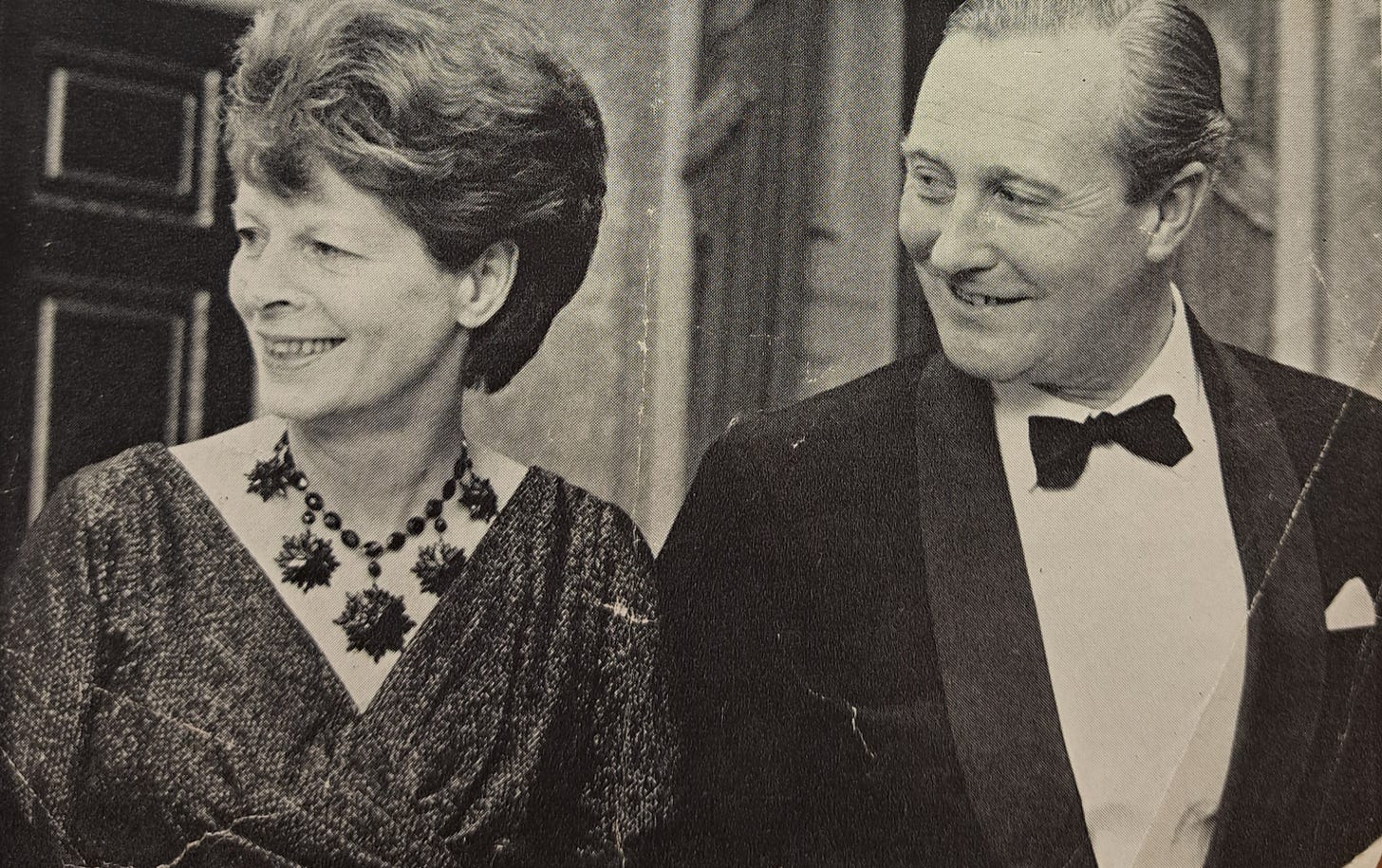

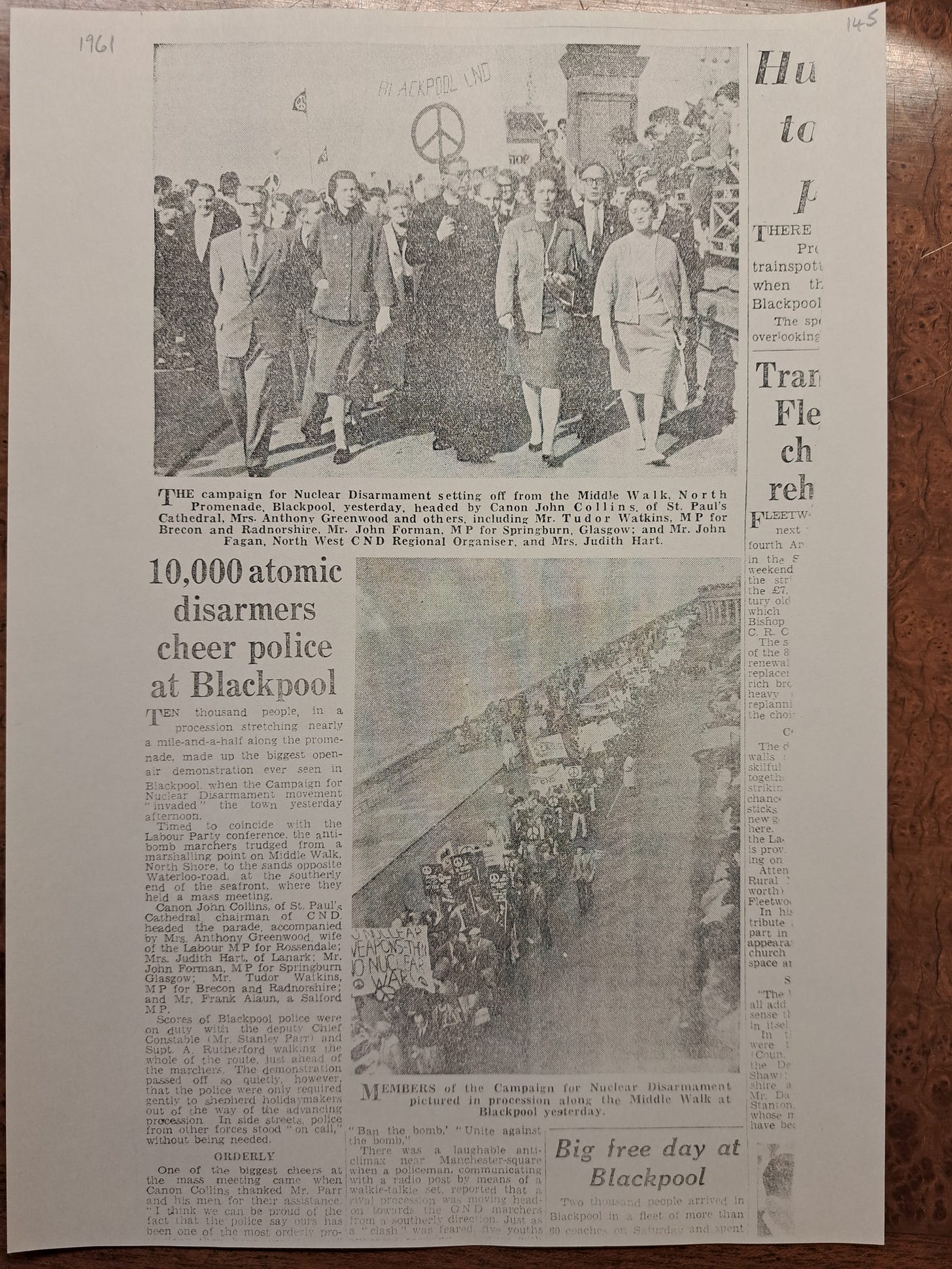

Gillian Greenwood’s memoir has little to offer about her later life, but she kept a scrapbook of press cuttings and letters which say a great deal about how she was perceived, as one of the most glamorous and interesting of MPs’ wives, likened to Katharine Hepburn and always stylishly dressed. She and Tony had two daughters, Dinah and Susannah. Tony was elected as Labour MP for Rossendale in 1946 and worked his way up though the party hierarchy, a loyal supporter of Harold Wilson. Gillian began to have her own profile beyond that of street lighting and window display design. Furthermore, her forthright political opinions were seen to be making a mark on her husband’s career. She said in her memoirs that she had become a socialist at the age of twelve, appalled by the plight of the starving miners in South Wales. Gillian and Tony were supporters of unilateral disarmament, a campaign that would cause many rifts in the Labour Party, and it was Gillian who convinced Tony to make a stand against the Gaitskellites and join the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Here is Gillian (second from the left) leading a march of ten thousand protesters at Blackpool to coincide with the Labour Party Conference.

In 1963 Gillian was appointed organiser of the Cobden Trust, which had been formed to raise funds for the National Council of Civil Liberties. Around this time, she gave up her career in window display design, saying that she wanted to do something more practical to help people. She started teaching display skills at Tottenham Technical College, and giving art classes in old people’s homes. She was also kept busy with her award-winning garden and window boxes at the Hampstead family home. In the 1970s she was a member of the working party that produced the Snowdon Report on integrating disabled people into the community.

Tony Greenwood died in 1982, and shortly afterwards Gillian sold the family home in Hampstead and set up a charitable foundation with the money, with the purpose of making small, useful donations to local people in need, such as an old man who could not afford a suit to go to his wife’s funeral. When the money began to run out, Gillian tried to raise more by selling her paintings.

Gillian Greenwood died in 1995. Tam Dalyell, in the obituary he penned for the press, described her as ‘a thoroughly good woman and a good socialist.’ I suspect she would have been very happy with that. However, in her archive is a letter written to her in 1952 by Humphrey Tomalin, the Chairman of Jaeger. In it he writes

Last night I was at a party where someone started the usual discussion as to whether a woman can have a career and a domestic life at the same time. As usual, the consensus of opinion was that it is impossible. You however are an outstanding proof of the contrary. By adding politics to these other activities you have actually brought off a treble.

He continued by paying tribute to the contribution she had made to the aesthetics and gaiety of the Jaeger scene. Gillian wrote at the top of the letter ‘I am now 74 and still thrilled by this letter. Jill Greenwood, known as Crawshay.’

I believe she would have been just as happy to have this as the final word.

Such an extraordinary woman. I've often wondered about the women behind the Make Do and Mend book, and it's great to "meet" at least one of them and find out so much about her too.

And as an aside - that amazing necklace of hers. Onyx or something with big... sunflowers? Stars? She's wearing it in the photo at the top with her husband, and the portrait photo of her at the end too. What a statement piece!

I've so enjoyed learning about this remarkable woman. What an eventful and useful life. I loved what Tam Dalyell said about her in her obituary. Beautiful.

Thanks Sarah!