It seems to me, and I’m no expert, that the 1920s is when women’s literature really took off in the English-speaking world. Of course there are marvellous earlier paragons of literary genius - Jane Austen, George Eliot, the Brontes, as well as the likes of Mrs Oliphant, Miss Yonge and Mrs Humphrey Ward to fill out the British publishing catalogue. Yet, whether driven or inspired by the end of the First World War, the enfranchisement of the female population, or the pronouncements on the subject by Virginia Woolf, women really did begin to find a room of their own, and picked up their pens and started writing, passionately and professionally, in the 1920s. And not just in Britain - across the Atlantic, Edith Wharton was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, in 1921, for that glorious novel, The Age of Innocence. Suddenly ‘lady novelists’ were everywhere, no longer a figure of fun, and producing classic works that could stand proudly alongside their male counterparts, and which appealed to the increasingly affluent audience of independent women readers.

This week I’ve been re-reading two novels by English women who were contemporaries, who contributed significantly to this explosion of talent, and whose work has stood the test of time. Winifred Holtby was born to a farming family in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1898. Rosamond Lehmann was born into a wealthy and well-connected literary family in Buckinghamshire in 1901. They both were Oxbridge-educated: Winifred won a scholarship to Somerville College, Oxford, but did not take up her place until the end of World War One, by which time she had experienced some of the horrors of warfare, serving in the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps. Rosamond, three years younger, missed the war, but won a scholarship to Girton College, Cambridge in 1919. Both women graduated in the early 1920s: Winifred set off for London with her best friend, Vera Brittain, with the avowed aim of becoming a professional author and journalist. Rosamond chose to marry and move to Liverpool and then Newcastle with her husband Leslie Runciman, heir to a title and a fortune in the shipping industry. The marriage was a disaster, and broke down within a couple of years.

In 1923, Holtby published her first novel, Anderby Wold, to limited commercial or critical success. Lehmann, on the other hand, published Dusty Answer in 1927, which became a massive bestseller in the States as well as in Britain, partly owing to its slightly scandalous subject matter - the seduction of a young girl, and hints at homosexuality, both male and female. It reads well today, as a portrait of naive passion and coming of age. A Note in Music, published in 1930, was her second novel, and something of a disappointment as far as the critics were concerned. So neither of these two, Anderby or A Note, can be classed as their author’s best work. But apart from being published just seven years apart, they have in common such a similar plot, that I found it really interesting to look at them together, and to consider what it said to me about these two writers, and about the ambition and interests of female authors in this crucial decade. For both novels can be summarised as ‘a glamorous stranger arrives in a northern backwater and turns the life of a bored housewife upside down.’

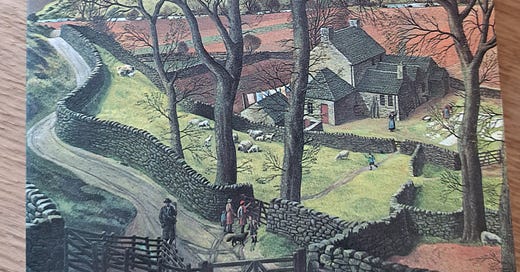

The heroine of Anderby Wold is Mary Robson, the wife of John and owner of a farm in a village outside Burton Agnes (Market Burton in the novel) in East Yorkshire. She is only twenty-eight, but her husband John, whom she married not for love but because she needed his help to save her farm from bankruptcy, is in his fifties. There is nothing glamorous about her, she is tall, ‘broad-shouldered and long-necked’ and behaves and dresses like a woman of forty, according to her more glamorous sister-in-law, Ursula. However, she is fiercely determined and rules her small village community with a firm but benevolent touch, something which makes her popular with some people, but less so with the dissatisfied, left-wing schoolmaster. She has no children, and finds it difficult to bond with her husband’s family. The story opens in the winter of 1912, as Mary celebrates paying off the mortgage on the farm. Then a younger man, David Rossitur, arrives in Anderby on a walking tour of Yorkshire. He is looking for material for his job, he is a radical Marxist journalist with a Manchester paper: his goal, to identify and document the oppression of the agricultural workers by their greedy landowning bosses. At first Mary is amused by his politics, and believes that her sympathy for him is purely ‘maternal’, he is clearly undernourished and unwell. But it soon becomes clear that the love she never knew was missing from her life has, inconveniently, come to call.

Grace Fairfax, the heroine of Lehmann’s A Note in Music, is a woman in her early thirties, married to Tom, a dull but kindly man working in the office of a manufacturing business somewhere ugly in the North of England, a grey town with screaming trams, deserted bandstands, slate roofs and red-brick chimneys. Like Mary Robson, her inability to produce a child has left a hole in her life that she is only too conscious of; her one friend, Norah has two children, but she too hides a sadness, that the man she really loved has been killed in the war. Mary and Grace in their two different novels have much in common: they have settled knowingly for second-best in the marriage stakes, bargaining financial security and companionship for sexual attraction and passion. But whereas the disturbing force in Mary Robson’s life comes in the shape of a red-haired radical journalist, with thin wrists and ill-fitting clothes, it is handsome, careless, aristocratic Hugh Miller who arrives in the Fairfaxes’ town and home, bringing his glamorous, divorced sister Clare with him. He is the heir to the business in which Tom Fairfax is working, and has arrived, in a casual way, to see if working in industry might suit him. Predictably, it does not. But by the time he leaves, Grace’s world has been up-ended, and she is forced to re-evaluate her life with Tom.

I’m not going to spoil anyone’s pleasure in reading either of these engrossing books by revealing the endings, suffice to say that one is much more shocking and heart-breaking than the other. Holtby places her interest in radical politics front and centre of her story: The National Union of Agricultural and Allied Workers (NUAAW) was a UK trade union representing farmworkers, founded in 1906, so the topic of farmworkers’ rights and their ability to combine was highly topical in the period when her novel was set. It is interesting, however, that the villain of the novel is the left-wing schoolmaster, and Holtby’s treatment of the journalist David Rossitur’s beliefs and his interaction with Mary, who is one of the more generous and philanthropic landowners, is balanced and no doubt reflects what Holtby herself had witnessed in the East Riding as she was growing up. Nevertheless, for Holtby, a committed socialist, her idea of a romantic hero is an articulate, passionate campaigner, whose looks are a secondary consideration.

Lehmann’s life was so very different from that of Holtby. After her first marriage broke up she married Wogan Philipps, from a similarly wealthy, titled family to the Runcimans. Philipps would later serve as an ambulance driver during the Spanish Civil War, and is famous for being the only member of the Communist Party ever to sit in the House of Lords. But their life together at the time that Lehmann was writing her novel did not by any means revolve around politics, rather around the glamorous and bohemian Bloomsbury set, as they stayed at Ham Spray with Lytton Strachey, and made friends with the Woolfs. So even though A Note in Music is set in a northern industrial town in the 1920s, there is no mention of class politics or unemployment. The romantic lead is a man of very little soul or purpose in life, surviving chiefly on looks and charm. This is not to say that there is no social conscience in the novel - there is a sub-plot concerning Pansy, the town prostitute, who has to support her disabled brother, and who falls for Hugh Miller as hopelessly as Grace. There is also some recognition of the plight of a woman who falls pregnant outside marriage. Yet A Note in Music does not aim at the political, but at a touching and well-drawn portrait of two highly realistic, disappointing marriages.

So here we have two novels, written by contemporaries only a few years apart, both dealing with the plight of the less-than-happily married woman. Literature in the 1920s has moved on from the Jane Austen marriage plot; Mary Robson and Grace Fairfax are both real women, described variously as thick-set, overweight, ageing, greying, and dealing with everyday household matters:

Ring up the plumber tomorrow, the damned plumber about the loathsome plug. Count the washing. Take a skirt to be dyed (Grace)

Or

A bowl of water placed in the middle of the room prevented it from reeking with stale tobacco for days after a party. She must go and get one. (Mary)

Women readers everywhere would identify with these stories, these plots, these characters. Ordinary women’s lives could become the stuff of novels. Women’s literature was changing, and Holtby and Lehmann were leading the charge.

* With apologies to The Dream Academy

You know how when you learn a new word you suddenly start seeing it everywhere? Your piece was one of those moments for me because I had just been reading about Rosamond Lehmann and the biography of Sir Stephen Runciman. I have never heard of her before and now I see her name everywhere

Oh, thank you for these - I agree that A Note in Music is very underrated, compared to the rest of Lehmann's output. I didn't know the Holtby, so thank you for that, too!

I'm with you on the 20s and 30s as a taking-off point for women's writing. It's not coincidental, surely, that the "Queens of Crime" found a good fit for themselves in the emerging genre of detective fiction, and came to dominate it.

Do you know Nicola Humble's The Feminine Middlebrow Novel 1920s to 1950s, which is very acute on all this stuff. And two by Diana Wallace are ace, too: The Women's Historical Novel 1900-2000. and her book Sisters and Rivals in British Women's Fiction 1914-39.