This is not my usual sort of post - I wrote it thinking I might try submitting it to Slightly Foxed: but on reflection I think they want pieces that will encourage readers to buy the book in question, and as you will see, I’m not sure I have ended up in the right place on this one. So here you are, it’s not about Victorian publishers or women’s literature of the 1930s, but I hope you find it intriguing, nonetheless.

It was July 1980. In Britain, Margaret Thatcher was celebrating her first year in office, unemployment had hit two million, and inflation was running at over 20 per cent. But I was seventeen, I had just finished my A’ levels: university awaited me in the autumn, and I was stepping onto a Laker Airways plane to Los Angeles for the most daunting, exciting expedition of my young life. Somehow I had wangled a two month job as an au pair to a half-British, half-Greek family living in Palo Alto, California. Marios was an up-and-coming urologist at Stanford University, his wife Jane was a nurse, and they had two obstreperous young children, twelve and eight, that I was expected to supervise over the summer while Jane studied for a postgraduate degree. I knew nothing about America, nothing about childcare, nothing about the household chores my mother had carefully shielded me from for years…but the one thing I thought I felt confident about, even though I was a fussy eater, was food. How different could that be?

The shock hit me the very first night, when I was still suffering from a debilitating combination of homesickness and jetlag. I crept downstairs to seat myself, ravenously hungry, at the family dinner table – to be presented with a lamb’s tongue, on a plate. Possibly accompanied by something green…In my memory, the tongue looked as if it had just been pulled from the animal’s mouth, it was covered with pimply skin and had some sort of muscle attachment at the back. I have only the vaguest memory of how the evening unfolded. But I am absolutely certain that I would not have been capable of eating a mouthful. I still could not, to this day.

There were many more surprises in store during my two months in California, beyond Jane’s extraordinary ideas about catering for strangers, including my first microwave cooker, my first Macdonald’s cheeseburger, my first Japanese meal – some of this went down well, some of it…not so much. But poking around Jane’s kitchen in search of something edible (you would not believe how many English Breakfast muffins with peanut butter I felt compelled to consume in the course of my stay), I stumbled across a book she had proudly acquired, as over the recent years had a million other American housewives: Laurel’s Kitchen.

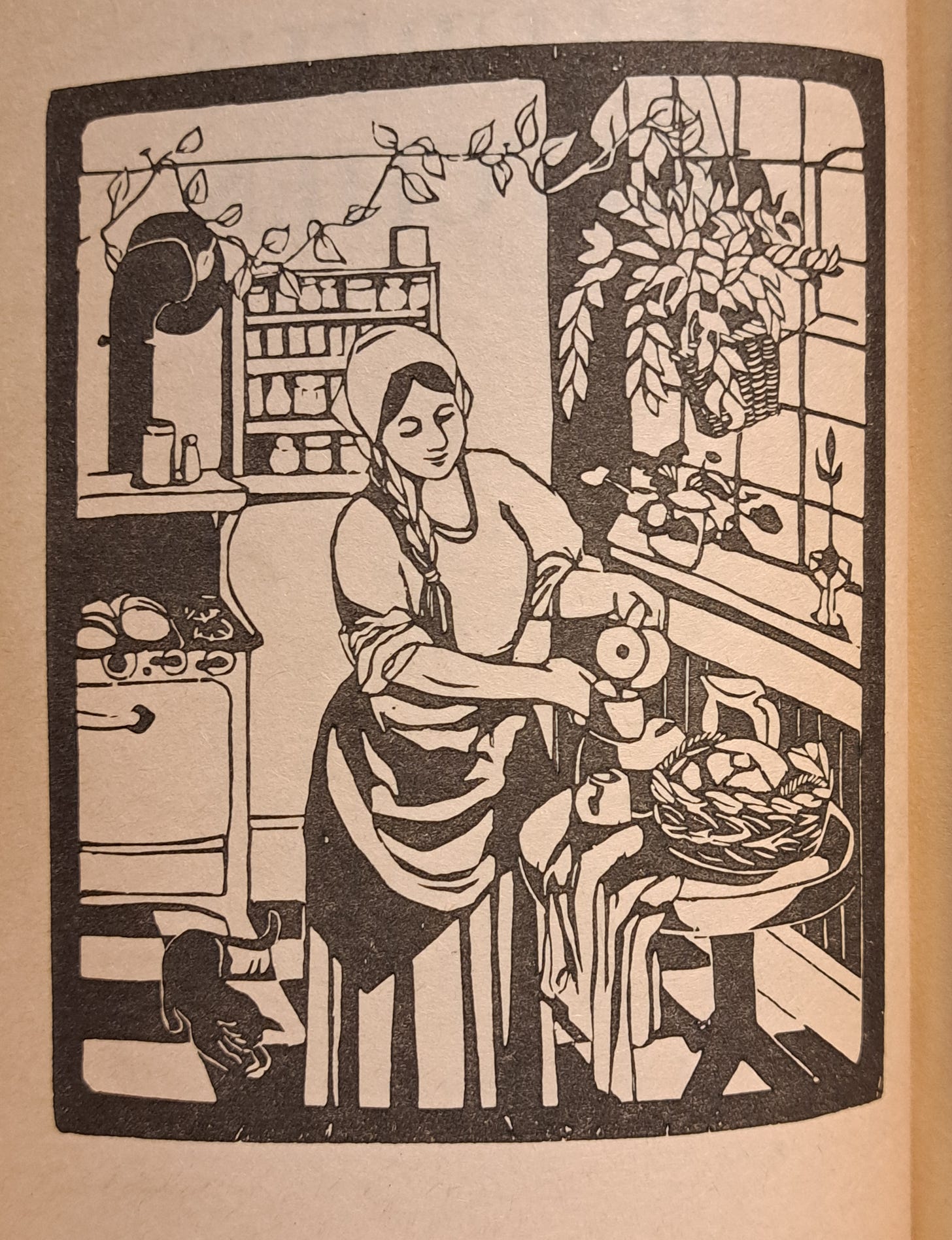

I had never seen a cookbook like it: no glossy photographs, no colour at all, only a few black and white linocut illustrations, contributed by one of the three authors. The first fifty pages were more than autobiographical, they were radical, polemical. There were nearly three hundred pages of charts and statistics at the back of the book on the nutritional values of the different food groups. I didn’t bother reading those. But sandwiched in between were two hundred and eighty pages of vegetarian recipes, starting with homemade breads of every description, and moving on through delicious breakfast suggestions (granolas and porridges), salads and soups for lunch, tempting curries and exotic quiches, rounding off with desserts. So many ingredients that I had never even heard of – eggplant, garbanzo beans, broccoli spears, squash, yams, zucchini, tofu…some of this turned out to be simple transatlantic translational issues. But, crucially for any teenager breaking away from home, there was absolutely nothing in the whole book that I could imagine my mother ever cooking. I was completely spellbound (and of course, extremely hungry most of the time – Jane’s cooking was not growing on me).

Having scoured the recipes, and imagining myself whipping up a plate of cheese-filled blintzes with apple sauce, or eggplant parmesan, I turned to the front of the book to discover more about Laurel. And this is where the magic really began. Laurel Robertson and her friends Carol Flinders and Bronwen Godfrey were three young housewives living in and around San Francisco and in Petaluma, up near Sonoma, all linked via the University of Berkeley. And they were happy to explain that they were part of a larger group, maybe twenty-five young women, who in the heat of the 1960s counter-culture movement, had taken their first steps into the world of vegetarian cookery. I imagine them now, baking their bread as they listened to Joni Mitchell.

Their journey was very much a spiritual commitment; they had met at meditation classes inspired by an Indian yogi…in fact the very first publisher of the book was Nilgiri Press, linked to the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in Northern California, and to famous translations of the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads. None of that meant anything to me, we weren’t truly au fait with the Upanishads in 1980s Dorset. But I was captured, entranced, by the image of Laurel in her kitchen, surrounded by friends, the smell of fresh baked bread in the air, a plate of cinnamon oatmeal cookies on hand, children playing round her feet. She was described by her friend Carol as ‘right out of Vermeer – a sturdy young woman in her early twenties with wide, clear blue eyes and a thick braid, her sleeves rolled up, a vast white apron over her long skirts.’

It was an idyllic image that has stayed with me, but not one I have ever been able to imitate. I did buy my own copy of this extraordinary book, and I have it still, forty-five years and at least eight kitchens later : it is extremely battered, the cover is long gone, and I would like to say that it is impregnated with wholewheat flour and creamed spinach… but therein lies my guilt. However compelling the language, however inspiring the words – we all just moved on to cooking, and eating, something quicker and tastier.

I wish this book had really had the impact it deserved. These radical women and their recipes had a message for America which has been repeated time and again over the fifty years since they first articulated it – a message that still falls on remarkably deaf ears. Listen to what they were saying back in 1976, when they identified ‘a growing suspicion that something was terribly wrong with our whole culture’s attitude to food.’ They had become painfully aware that across the world thousands of people died of malnutrition every day, while across the United States, most health problems seemed to be linked to over-consumption of food and alcohol. They had identified the unhealthy relationship between meat consumption and grain production, but also ‘twenty million people could live for a year on the amount of grain used by our beer and liquor industry annually.’ They talked about the sheer volume of food waste produced in the States every day, about unnecessary packaging, and about the reliance on fossil fuels in the fertiliser and plastics industries. ‘The signals register one by one in our consciousness like those red signs on the freeway: “Turn back, you’re going the wrong way.”’

The most extraordinary lesson from all of this is that these words were written FIFTY years ago, in a book read, or at least read about, by millions of American housewives. But Carol Flinders, the principal author of the book, who I believe is still living in California today, would be the first to admit that the Consumerist half of the world continues to plough the wrong way down the freeway, going faster and faster. The sad facts are that although I adored the book, I never became a vegetarian, I never grew my hair into a plait, and ‘children playing round my feet while I bake cookies’ sounds like an accident waiting to happen.

I’m not sure I ever even cooked from the book: I showed it to my mother on my return home, weighing a stone heavier (all those delicious peanut butter covered English muffins) and she laughed. Scorn can fertilise a true revolutionary’s heart, but my little rebellion shrivelled and died. If there was no room to recreate Laurel’s Kitchen in my parents’ house, it proved even harder for a student living in college on a grant, and then I started working in the City, doing 12 and sometimes 18 hour days. It left little time for proving dough and soaking beans.

Revisiting the book recently, I felt a certain guilt again for my beef-eating, gin-swilling life. But then I noticed a problem with Laurel’s philosophy that went some way to justify my failure to follow her path. It was right there in the foreword of my edition from a (male) Professor at Berkeley:

Warmth, concern for spiritual values in daily living, emphasis on family unity and on the invaluable role a woman can play in creating community – all these are things I have not found together in any other book of the sort. (my emphasis)

Today as I read about the American Tradwives movement, where beautifully if impractically dressed TikTok housewives extol the virtues of being stay-at-home mums, existing, apparently, only to provide for the needs of their husbands and children, I find these words chilling. I suppose it is the writer’s assumption that it is the woman who has to play the role, and create the community, while still finding time to cook the wholesome vegetarian food. When I was turning eighteen in 1980, that was my assumption as well. But then I discovered how much fun and self-confidence there was to be gained in having a career and earning money, compared to being stuck in the kitchen.

Saddest of all, I suspect, is how Carol Flinders must feel about the adoption of the ‘wife as domestic goddess in the kitchen’ trope by JD Vance and the far Right in the USA. How can such a radical dream have been so subverted?

This is my most beloved cookbook of all time. There's a lovely squiggles inscription from my then 2 year old son, and we cooked out of this for many many years. Moosewood too. But this one, was a treasure. She cut up oranges for her husband to pack in his lunch! She also made zucchini crusted pizza which my kids loved, and taught me how to think about alternative protein back in the early 80s when I was delving into such things as a 20 something, and this is where I first learned about Chillaquilles which my kids also adored. Sadly, I have lost this book ... it must be in a box somewhere. None of my kids have it and I would NEVER had given it away but I can't find it. To this day I think about it and am trying to recall it ...

On this side of the pond we had the arrival of the Moosewood cookbook. The original edition was similar in that it had no glossy photographs but focused on healthy and nutritious vegetarian fare based on the collective of local "chefs" who ran the vegetarian restaurant the Moosewood in Ithaca, NY (still in operation). It inspired more than one generation of vegans in the kitchen here.