Lady Baker and the source of the Nile

From a Bulgarian slave market to the toast of the Royal Geographic Society

Among the thousands and thousands of handwritten letters preserved in the British Library from the pen of the Victorian publisher Alexander Macmillan, one in particular piqued my interest: written to the heroic explorer of the sources of the Nile, Sir Samuel Baker, on 4 May 1866:

There is a terrible defect in your summing up. You should say something about Mrs Baker. It may be as slight as you please, very little more than your most tender and delicate allusion at starting, but indeed something should be said. You mention Richarn [sic: one of the bearers] and his wife and your man. It struck me as strange to a degree. Of course I understand your feeling of not wearing your heart upon your sleeve, but I do think people would wonder.

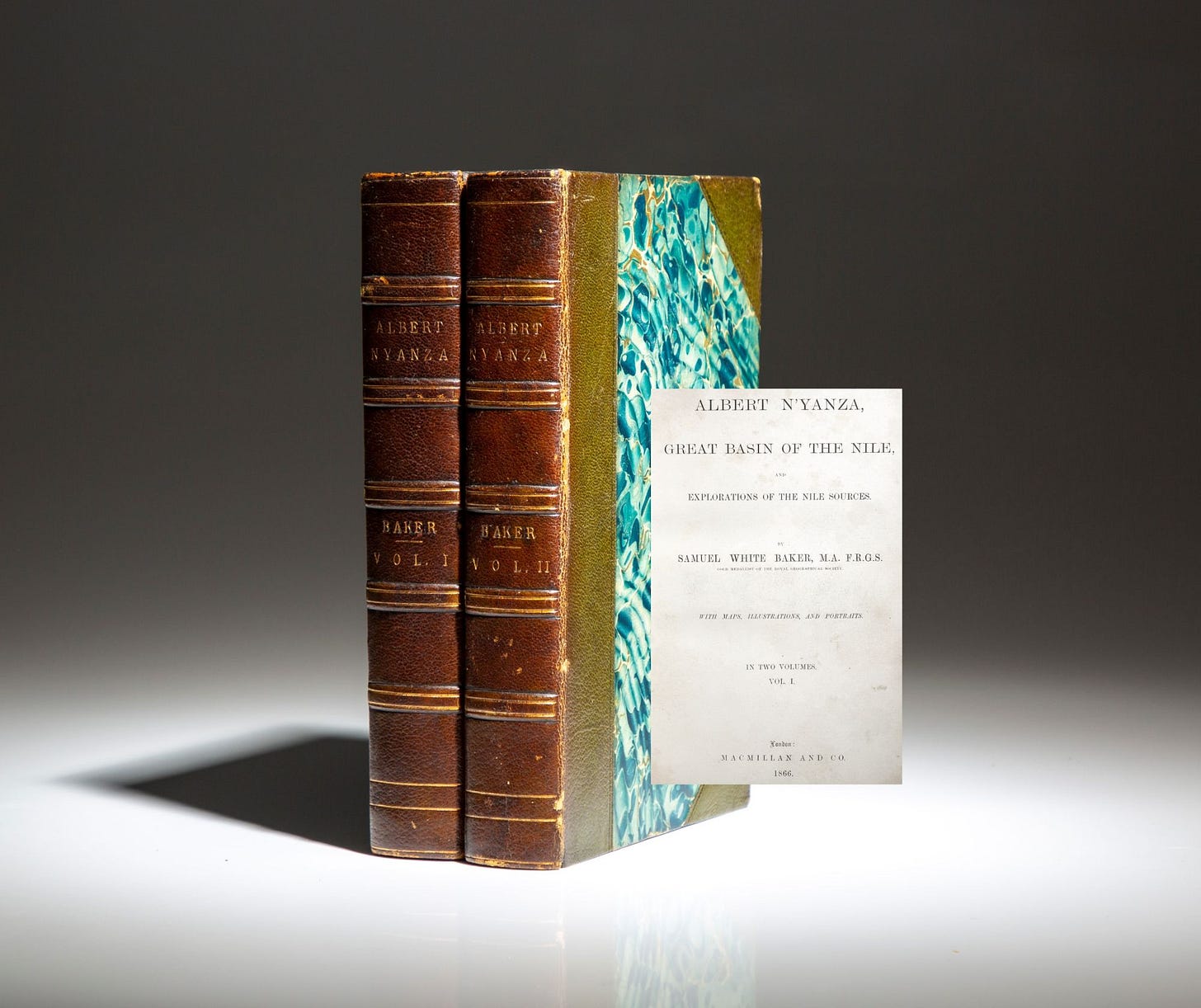

The book in question, still in draft at this stage, was Samuel Baker’s classic tale of adventure Albert-Nyanza: Great Basin of the Nile, a title that Alexander Macmillan had gone to great lengths, and considerable expense, to secure. The publisher was determined that nothing should be lost in the promotion of a story that was fascinating the Victorian public.

The English reading public in the 1860s was completely gripped by tales of foreign adventure and expedition, and no-one more so than Alexander, who had also spotted a lucrative publishing opportunity. The topic of burning interest was the search for the source of the Nile, and the country thrilled to stories of bravery and missionary zeal from David Livingstone, and to the conflict of egos that marked the return from Africa of Richard Burton and his erstwhile companion, John Hanning Speke, which had culminated in Speke’s tragic death, on the eve of a great debate between the pair, in a mysterious shotgun accident.

As Samuel Baker was to put it, in the preface to his book:

In the history of the Nile there was a void: its Sources were a mystery. The Ancients devoted much attention to this problem: but in vain. The Emperor Nero sent an expedition under the command of two centurions, as described by Seneca. Even Roman energy failed to break the spell that guarded these secret fountains. The expedition sent by Mehemet Ali Pasha, the celebrated Viceroy of Egypt, closed a long term of unsuccessful search. The work has now been accomplished. Three English parties, and only three, have at various periods started upon this obscure mission: each has gained its end. Bruce won the source of the Blue Nile; Speke and Grant won the Victoria, source of the great White Nile, and I have been permitted to succeed in completing the Nile Sources by the discovery of the great reservoir of the equatorial waters, the ALBERT NYANZA, from which the river issues as the entire White Nile.

Alexander had tried to make some African capital out of his previous acquaintance as a young man with David Livingstone, but despite several letters had not been able to squeeze so much as an article for Macmillan’s Magazine out of the great explorer. But late in 1865, as the newspapers thrilled to the exploits of Samuel Baker, who had discovered and named Lake Albert Nyanza as a previously unknown source of the Nile, Macmillan was contacted by Baker’s family and offered the chance to bid for Baker’s memoir. Fortuitously, he had published a couple of pamphlets concerned with the military volunteer movement in the early 1860s written by Samuel’s younger brother James. His negotiations with Colonel Valentine Baker, another of Samuel’s brothers, show that he was prepared to risk a truly significant amount of money to capture the prize. In November 1865, Macmillan wrote to the Colonel offering an advance of £4,500 plus half-profits, or £2,000 up front and two-thirds profits to the author. For comparison, Alexander had only paid £500 up front to WG Palgrave for Travels in Arabia. After some brinkmanship on the part of the Baker brothers, Macmillan was pushed to £2,500 up front and two-thirds profits, a huge gamble.

So, had Alexander’s cautious letter to Baker been caused by rumours that might have explained Baker’s reticence about his wife? Or was this an extremely tactless suggestion? Baker was very nervous about discussing the role Florence had played, with him throughout his appalling and dangerous trek across Africa. She had nearly died on more than one occasion, and had saved his life on others with bravery and skilled nursing, and yet she is seldom mentioned in the book. The truth that would have shocked his Victorian readership to the core was that Florence was not his wife at any stage in their African adventures, and they were only married on their return to London in November 1865.

Samuel had found nineteen-year-old Florence, as he called her, in 1859 at an auction of white slaves in a Turkish-administered town in Bulgaria. (There is some date about her exact age: she was certainly less than half Baker’s age when he met her.) Her real name is believed to have been Barbara Maria von Sass, born in Transylvania, then part of Hungary. Her parents had been killed in the 1848 uprising, and she had been raised from her childhood by a wealthy Armenian trader who intended to make a good profit when he sold this beautiful blonde teenager at auction. Baker saw her, bought her, and subsequently fell in love with her. The pair became inseparable, but the longer they were together, the worse Samuel’s problem became: how was he to explain this relationship to his four daughters at home, who he had left with their aunt after his first wife died? He took a job as managing director of the Danube and Black Sea Railway as an excuse to stay in Romania with her. But by 1861 the lure of an African adventure, on which he could take her with no questions asked, while also seeking fame and glory as an explorer, had overtaken him.

I am not the writer who can detail the couple’s travails and discoveries over the next four years, and this would not be the place to do it. If you want a very readable account of all the Victorian explorations of Africa, I would recommend Explorers of the Nile, by Tim Jeal. Several officials who met the couple at the start of their journey in Egypt warned Baker that he was mad to take a woman with him, and throughout the journey Baker was only too aware that Florence’s plight, were she to be left alone among the ruthless Arab slave-traders and the warring African tribes, would have been worse than her position back in the Bulgarian slave-market. But throughout their journey, and despite appalling illness, her bravery and resourcefulness seems to have inspired him to persevere until they reached the vast expanse of water, Lake Nyanza, that they had been looking for. She dressed in trousers, gaiters and her husband’s shirts; she was fluent in Arabic and could enter into negotiations alongside Samuel with the Arab slavers who they had to rely on for protection; when they were compelled to stay in any one place for any length of time, Florence would keep hens and plant lettuces, onions and yams. She tried making wine, she kept a pet monkey, she sewed Robinson Crusoe style garments for herself and her husband.

The journey back from the Lake was even more terrible: they had exhausted all medical supplies, most of their attendants and their donkeys and oxen had died or fled. Sometimes they survived only by digging up buried grain in burnt-out villages. Baker would keep Florence’s spirits up by telling her tales of English beefsteak and pale ale. When they eventually made it back to the comparative civilisation of Khartoum, Baker delayed another two months while he tried to decide what to do about Florence. Eventually he cabled to his brother James asking him to arrange a quiet wedding, witnesses only, for November 1865 in London, and with Florence as his lawfully wedded wife, the Bakers were finally ready to meet their public. Sir Roderick Murchison, President of the Royal Geographical Society, wrote to a friend about Baker’s ‘little blue-eyed Hungarian wife, who …is still only 23 years of age and who we all like very much.’

A week after the wedding, Baker was awarded the Society’s Gold Medal, and was given the opportunity to regale the assembled company with his story. As his talk came to an end, he declared:

‘There is one other whom I must thank…one who though young and tender has the heart of a lion and without whose courage and devotion I would not be alive to address you tonight - Mr President, my Lords, ladies and gentlemen, allow me to present my wife’ and, from the wings to centre stage he ushered his immaculately dressed, beautiful young bride, to a standing ovation.

The final paragraph of the book as published by Macmillan pays a lovely tribute to Florence. ‘Had I really come from the Nile Sources? It was no dream. A witness sat before me; a face still young, but bronzed like an Arab by years of exposure to a burning sun; haggard and worn with toil and sickness, and shaded with cares, happily now past; the devoted companion of my pilgrimage, to whom I owed success and life – my wife.’

Baker had taken Alexander’s advice to heart, realising that it was the presence of a woman on this journey which differentiated his book from competitor titles. The public loved Florence and thrilled to the dangers undergone by a white woman in darkest Africa, as they saw it. Samuel was knighted in August 1866 and Florence became Lady Baker, but the rumours about her origins continued to rumble: Queen Victoria refused to receive her at Court, despite her delight that Samuel had named his great lake after her beloved Prince Albert. In 1869 the couple returned to Africa when Samuel was appointed Governor General of the Nile Basin and charged with trying to bring the slave traders under control. Yet again Florence played a key role in defending her husband from a tribal attack, wielding pistols, rifles and medicinal brandy like a professional.

Samuel died in 1893 but Florence lived on quietly in their Devon estate until 1916. The couple did believe they had found the source of the Nile: this claim has not stood the test of time, but they should still be remembered for their discovery of Lake Nyanza and of the Murchison Falls, and for all they did to try to counteract the Arab slave trade in East Africa.

You can read more about Alexander Macmillan’s publishing exploits here, massively reduced in advance of the paperback edition!

Hollywood needs this story!

Such a fascinating period of history! I read Candace Millard’s River of the Gods several years ago, but its focus is on Burton and Speke. Delighted to be introduced to Lady Baker!