‘That little bastard that I have hugged to my bosom and cherished, that all the others have tried to kill off, will thrive.’

Jennie Lee, July 1967

No-one seems to be quite sure who first had the idea for the Open University. Some claim it for Michael Young, social scientist and political theorist. Certainly Harold Wilson considered it his own baby, and the crowning achievement of his first government. Perhaps if it had had just one progenitor, watching its birth would feel less like watching Jeremy Clarkson open a pub. And yet it survives, fifty-five years old, the largest university in the United Kingdom by number of students, with two million alumni. The credit for taking the vague ideas and aspirations of Wilson and Young, and melding them into a Government White Paper, then into a Charter, and finally into a flourishing University, surely belongs to the indomitable, infuriating, utterly charming Jennie Lee.

In September 1963 Harold Wilson, the newly elected leader of the Labour Party, needed content for a speech he was giving in Glasgow. He cast his mind back to a recent visit to the United States, when he had spent time with a friend, Senator William Benson of Chicago, the owner of Encyclopaedia Britannica, a man heavily involved in the creation of distance learning programmes using television lectures. The result was Wilson’s announcement of his ambition to create a ‘University of the Air’. Michael Young had also been influenced by a trip abroad - to the USSR, where he had seen schemes that enabled adults to study from home. However, Wilson and Young were not necessarily driven by the same ideological goals. To Wilson, there was an urgent overwhelming need to upskill the British population: the achievement of the ‘White Heat’ of technology, crucial to his election campaign, would require many thousands more scientists, engineers and technicians if Britain was to compete in international markets. For Young, the question was equality of opportunity: he saw the existing universities as bastions of privilege for the elite, sustaining the unproductive British class structure.

Statistics proved that both men were right: only four per cent of school leavers in Britain were going on to university, compared to eight per cent in Europe and fifteen percent in the USA. New universities were opening around the country, but they seemed to be filling up with the middle-class girls who had found it difficult to win places before - and they mostly weren’t studying science. The working classes were still not getting a look-in, and those who missed the boat as teenagers found it impossible to catch up, there were so few opportunities to study or gain degrees on a part-time basis.

Wilson’s original idea was to institute nationally organised correspondence courses, primarily in technical subjects, for adults with no previous qualifications. These courses would be delivered through television broadcasts, and would lead to degrees awarded by one of the existing universities. There was a suggestion that a new fourth television channel could be launched, dedicated to adult education. The scheme rapidly became mired in debates about cost, commercial advertising and management, and the project seemed to be doomed to fail before it had even begun, despite Wilson’s election victory. The Universities were sniffy, the Press dismissive (did we need more ‘flower-arranging courses for housewives’? ). The Department of Education, led by Tony Crosland, was unenthusiastic, its main priority being the creation and construction of the comprehensive school system. In exasperation, Wilson turned to Jennie Lee, appointed Minister for the Arts and sitting within Crosland’s Department: ‘For God’s sake get this thing going’. From then on, Lee had Wilson’s unconditional support - whenever she hit an obstacle, she just picked up the phone to Number 10 and it miraculously cleared.

To Jennie, it was a new idea, not a policy that she had been involved with before her appointment. Now she picked up the ball and ran with it like Stuart Hogg in front of a Murrayfield crowd. The Department officials showed her a proposal they had been working on: she tore it up and told them to start again. She was inspired by a far more ambitious vision; her university would be an independent body offering its own degrees, no entrance qualifications needed. She set up an advisory body which she herself would chair, against usual Civil Service protocol, which met for the first time in May 1965 and delivered its report just two months later. Jennie’s team of advisers took this report and used it to draft a White Paper that was delivered to the Cabinet in February 1966. This speed of decision making is something we seem to have lost today. Meanwhile, the Civil Service Official Committee had performed a costing exercise for the ‘University of the Air’ using the fourth TV channel. It concluded that it would need £42 million of capital expenditure (£750m at today’s values) and would cost £18 million per annum (£320m) to operate. In cash-strapped Britain, this was a non-starter. The paper that Jennie presented to Cabinet was much more modest and required only fifteen hours a week of existing BBC 2 broadcasting time.

The Labour Party manifesto, published for the 1966 General Election, contained the following:

The Open University

We shall establish the University of the Air. By using TV and radio communal facilities, high grade correspondence courses and new teaching techniques, this open University will enormously extend the best teaching facilities and give everyone the opportunity of study for a full degree.

It will mean genuine equality of opportunity for millions of people for the first time. Moreover, even for those who prefer not to take a full course, it will bring the widest and best contribution possible to their general level of knowledge and breadth of interests.

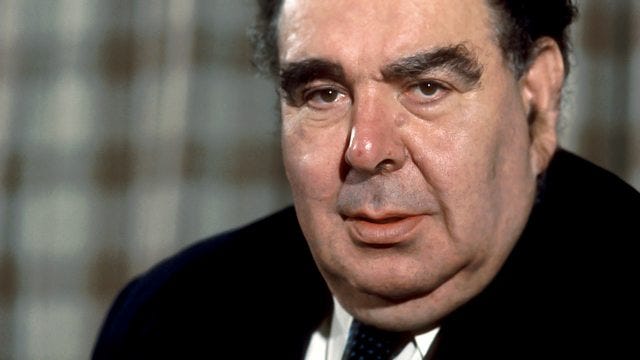

Michael Young had first used the term ‘Open University’ in 1962: Jennie now adopted it as her own, as she wished to emphasise the community nature of the project, and the ‘University of the Air’ faded from view. Cabinet asked how much her new plan would cost, and with Wilson’s agreement the question was passed to arch-fixer Arnold Goodman, recently ennobled, to investigate with Sir Hugh Greene, Director General of the BBC.

The two men did not spend much time on the subject, and came back with the very encouraging view that the BBC could provide 32 hours a week for capital expenditure of £1 million, and an annual operating cost of around £2 million. This was outrageously short of the mark: in 1974 Lord Goodman said ‘When I see the figure I mentioned, and the figure it is now costing, I ought to blush with shame.’ Thus, purely by accident, the Open University became a practicable proposition. (For those of you enjoying the Clarkson analogy, The Farmer’s Dog, based on a very dodgy budget, and on a stupidly ambitious timetable, now sprang into life.)

The General Election was held on 31 March 1966 and Labour found itself with an increased majority and the ability to pursue its manifesto commitments, including the Open University. However, Jennie still had an uphill battle to win. As the New Statesman wrote during the election campaign ‘The Press was lukewarm, educators were doubtful about ends, broadcasters about means and the public was unstirred.’ The papers were still full of snide comments about who would be most interested in taking up these degree courses, incidentally demonstrating massive contempt for the middle-class housewife who apparently had no right of access to better education. But Jennie continued to believe, and to say at every opportunity, that the Open University would be as transformational to the country as her beloved Nye’s NHS had been. When critics argued that she could not really say what it would cost, she would reply that no-one really knew what Concorde would cost, but it was still going ahead.

By September 1967 Lee had assembled a formal Planning Committee, whose nineteen members included Asa Briggs, the president of the WEA, as well as the Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University. Its academic credentials were being established. The 1963 Robbins Report had tried to quantify how many people had missed out on getting a degree because of the War, their personal circumstances, poor schooling or lack of places. There were no proper estimates of demand for what the OU would offer, but it was agreed that if just 10 per cent of those who had missed out, were added to the 250,000 teachers who had no degrees, the University would certainly find a market.

Lee began to assemble the team of academics who would actually run the University. Tony Crosland lobbied for his friend Michael Young to be appointed Vice-Chancellor but Jennie blocked it - she thought he would be seen as a political appointment and she wanted it to be a ‘proper academic’. The job went to Walter Perry, aged 46, a Vice-Principal from her alma mater, Edinburgh, and a pharmacologist.

Jennie took premises for the team at 38 Belgrave Square, in central London, wanting it to look suitably prestigious, and equipped it with comfortable furniture. In an incident that Jeremy Clarkson could have scripted, the first day the team sat down in the staff room, the chandelier fell from the ceiling and covered them all in plaster dust. Luckily, no casualties.

So much of the establishment of the University was serendipitous. As the project grew, the need for staff and premises mushroomed far beyond any original blueprint. Jock Campbell, Chair of the Milton Keynes Development Corporation, was on his way to meet Sir Geoffrey Crowther, Chancellor of the OU but also Chairman of Trust Houses Hotels, because he wanted a Trust House in Milton Keynes. In the taxi he read that the OU was searching for premises. He greeted Crowther saying ‘I wanted a hotel. Now I want a University.’

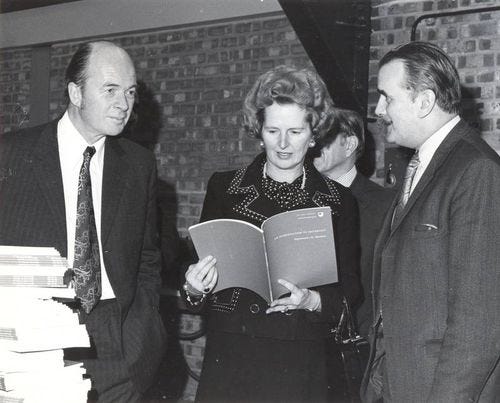

By 1969, Milton Keynes had been selected as the site for the main buildings, and a University Charter had been drafted and received Royal Assent. But the race was on: the Conservative Party were resolutely opposed to the whole project. Iain Macleod, shadow Chancellor, called it ‘blithering nonsense’, and the Shadow Education Secretary, Margaret Thatcher, seemed convinced that it was simply offering ‘courses in hobbies’. None of this might have mattered - except that there was a strong likelihood of a 1970 General Election. Perry realised that if his University was to survive, it had to be operating with students, it had to have premises, and it had to distance itself from the Labour Party. Jennie was evicted from Connaught Square. The wooing of Margaret Thatcher began in earnest.

According to Lee’s biographer Patricia Hollis, the wooing began with a dinner: Crowther invited Mrs Thatcher to meet Perry at his club for dinner. She fired questions at Walter all evening, and then left. Perry turned to Crowther and apologised for having blown it. Not at all, said Crowther, you did the job, and she has her brief. From then on, Thatcher became a firm fan of the project, and was prepared to fight for it against Macleod in Cabinet once they were in power. Three weeks into Macleod’s tenure at the Exchequer he had the papers sitting on his desk to close the OU down, when he was struck down by a fatal heart attack. Thatcher persuaded his successor that the OU was a cheap route to upskilling the nation, and the project survived. She should take appropriate credit for saving the Open University.

The first students were to commence in January 1971. The race to be ready was extraordinarily stressful (and would actually give Perry a coronary in December 1970): admissions would have to be completed by summer 1970, which meant that the prospectus had to be at the printers by October 1969. However, the academic staff who had agreed to join (and many would not, because it seemed such a high-risk project) would not be available until September 1969. Perry brought his staff together and they planned the foundation course in one day. The site was a sea of mud, but a cellar bar was opened, and Jennie ceremoniously hung Nye’s flat cap above the bar.

The OU started advertising in January 1970, and received 10,000 enquiries in the first two weeks. By the time of the General Election in July they had 140,000 enquiries and 43,000 firm applications. The university was unstoppable.

When Jennie lost her Cannock seat in 1970, partly because she had spent so much time on her ministerial projects that she had badly neglected her constituency, Wilson promoted her to the House of Lords, where she continued to speak on behalf of her precious university, and worried every time the fees increased. In a debate she said ‘The very essence of the OU is that it should not be for the rich or the poor, for black or for white, for men or for women, but it should be judged on its academic standards and be available to all.’ Jennie always defended the right of the housewife to want further education, in fact, she said, ‘she was very proud of them.’ Many thousands of teachers used the OU to gain degrees and thus promotions. The OU established hardship funds for the really poor student: most were paying fees from their own pockets. It ran summer schools, including for students with disabilities. It went into prisons and into the armed forces. Albert Mansfield, founder of the Workers’ Educational Association, had created the College of the Seas to allow seamen to access distance learning: he would have been delighted to see what the Open University would do with this project. Meanwhile the academics rapidly established high quality research facilities and developed an international reputation: Harold Wilson’s son Robin would be a Professor of Mathematics there for many years.

The first degree ceremony was held on 23 June 1973, with 900 graduates assembling at the Alexandra Palace. Honorary degrees were given to, among others, Michael Young, Sir Hugh Greene of the BBC, and of course Jennie Lee, the mother of the University. Michael Young would write ‘The OU was built by one person - though she had many able lieutenants and one ace card…the direct support of the Prime Minister…it was a stunning performance.’

Jennie believed that as Minister for the Arts, she had the best job in Government.

‘All the others deal with people’s sorrows…the tidal wave of past neglect. But I have been called the Minister of the Future.’

Fascinating, and brilliantly researched

An inspiring story, wonderfully told. Thank you!