Greengates

What came after Journey's End?

I am beginning to develop a passion for English novelists of the inter-war period - not so much the well-known ones, Woolf, Waugh, Orwell, Greene, although I love them too, but those lesser-known writers of domestic comedy and drama: EM Delafield, Elizabeth Von Arnim, John Moore, Winifred Holtby, Rosamund Lehmann. These are novels that you can pick up at any time, safe in the knowledge that the language will be fresh, interesting but simple, the plots will feature everyday events and locations, the writing will probably start at the beginning, have a middle and an end just where you expect them to be, will be rich in observation, have comic touches and relatable characters, and will warm your heart. I know that I am not alone in this enjoyment – these books and authors are now the staple of wonderful publishing imprints such as Persephone Books | Twentieth century women writers and Slightly Foxed Books.

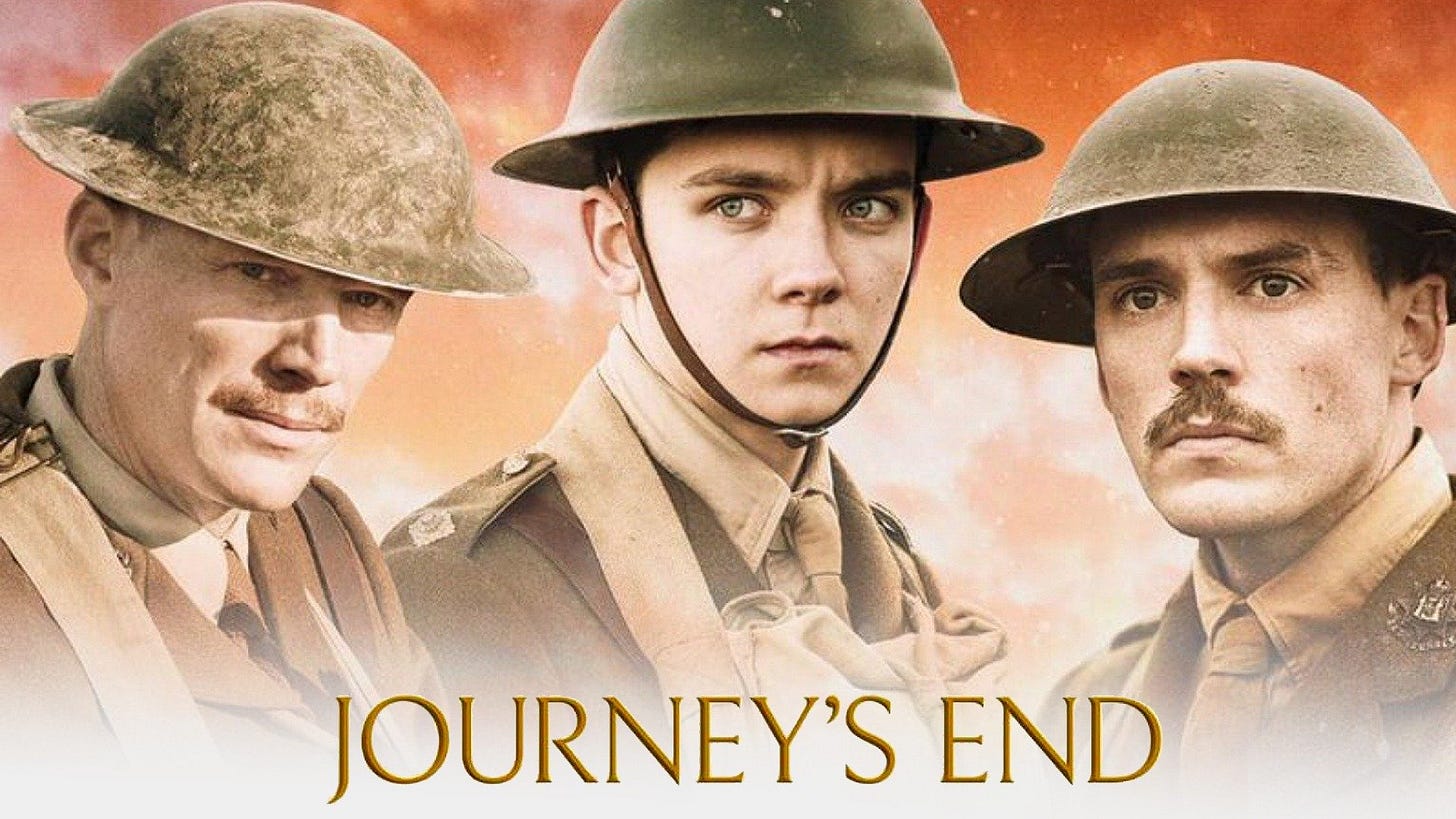

My particular passion at the moment is RC Sherriff – a name you might more usually associate with his most famous work, the harrowing play of life in the trenches, Journey’s End. But I want to talk about one of several domestic comedies he wrote in the 1930s, Greengates.

If you want to be totally and happily immersed in cosy 1930s English suburbia, this is the one for you. The story opens on an auspicious day: Tom Baldwin is retiring from his position as Chief Cashier in a City firm, clearing his desk after forty-one years’ service, being ceremoniously handed that hackneyed retirement present of a mantelpiece clock, and setting off home for the last time to his house in Brondesbury, a nondescript stop on the tube line between West Hampstead and Kensal Rise. He is only fifty-eight, and is therefore rather upset to see a headline in the evening paper ‘Tragedy of Retirement’, about a civil servant who had hanged himself in Ruislip. But he is full of plans to make his own retirement busy and fulfilling, with studying, gardening, all the things he never had time to do when he worked. At home his wife Edith is nervous of the forthcoming disruption to their lives. After dinner, Tom starts to work down his list of retirement projects – he can finally tackle the great twelve-volume History of England left to him by Uncle Henry…but within minutes he is fast asleep. So he goes to bed, taking his new clock with him.

Tired though he was, it took him some little while to settle down, for cheap clocks, like crickets, chirp stronger as the night wears on. First he had to get up to cover his new present with a towel. A little later he had to get up again to put the clock, towel and all, into the wardrobe cupboard.

Of course, in no time at all, the new regime is causing havoc with the lives of Edith and the Baldwins’ loyal old servant Ada. The housekeeper’s patience is particularly tested when Tom decides to start clearing up the garden: Tom’s tussle with her over the ownership of the broom is laugh-out-loud comedy. Then Edith is disturbed to find Tom has taken possession of her ‘afternoon nap chair’ after lunch. All very relatable, all very funny.

Tom is conscious that he is worried about how to fill his days. Edith’s dilemma is, if anything, even harder to face:

She had foreseen Tom’s battle, but she had not foreseen her own; and while his battles were clear to understand and easier to grapple with, hers were obscure – the more difficult because she must fight on lonely fields in secret… How could she say that his constant presence in the house was making her life unhappy? That his only way of helping her would be to go out, and stay out, for eight hours a day?

The three inmates of ‘Grasmere’ seem to be heading for a crisis, and while we can laugh at their irritations and upsets, it is so perfectly written that we uncomfortably recognise our own little selfishnesses, routines and foibles in their behaviour. But just when things seem to be plunging towards disaster, Tom and Edith find salvation in a project that will utterly consume their energies, unite their endeavours, even rekindle their marriage. An afternoon’s walk in the woods out of London, north of Hendon, to a spot they remember from their days of courting, leads them to a housing estate under construction, and changes their lives. They have found ‘Greengates’. Their subsequent difficulties with banks, builders, valuers and estate agents are all too familiar to us today, but buying this house opens them up to a whole new way of living.

This book makes me roar with laughter, and I could quote paragraph after paragraph to prove my point – except that I want you to find it for yourself. Yes it is a novel about navigating retirement, something for us all to think about at some point, but also about marriage, about starting again, about finding your true self. Tom and Edith’s new lives are ten times more fulfilling than anything they had experienced before. Although it may not be a life everyone would choose, with its village committees and sports clubs and societies, we as readers are so invested in the Baldwins’ happiness and fulfilment that we can only look on enviously, and hope that our lives may be equally full of purpose and joy.

Richard Cedric Sherriff (1896-1975) could have found himself living Tom Baldwin’s life. He was born in Hampton Wick, Middlesex, he left school without going to University, and spent ten years working as an insurance clerk in the City. In his spare time he took up rowing and it was to raise money for the Kingston Boat Club that he first put pen to paper, writing plays. There was no immediate success: but his seventh play was put on for a single performance one Sunday afternoon, featuring an unknown 21-year-old actor called Laurence Olivier, and was picked up by a West End impresario. It ran for two years at the Savoy Theatre, and transformed Sherriff’s fortunes. The play was Journey’s End, and it was based on Sherriff’s terrible experiences in the First World War. He had served as an officer fighting at Loos and Vimy Ridge, before being severely injured at Passchendaele.

After Journey’s End, Sherriff’s life took a completely different turn. He took himself to University, for a start. There followed a string of novels, plays and well-known screenplays, including Goodbye Mr Chips and The Dambusters. Another wonderful novel in the Greengates mould is The Fortnight in September, you can read a good piece about it here:

For several years in the 1930s Sherriff worked in Hollywood, writing scripts that he hoped would boost the British cause as war loomed, but returned to England in 1944. He never married, living with his mother in a house, Rosebriars, that he built for them both in Esher. His fortune, from the continuing royalties of his plays and books, including the 2017 film of Journey’s End, was divided between his old school and The Scouts Association. Rosebriars was sold and the RC Sherriff Trust established in his memory, giving grants to ‘advance the arts and enhance culture in Elmbridge’.

In his autobiography Sherriff wrote:

Once you have tasted the joy of writing you can never give it up. You can kid yourself that you’ve finished, but you can’t stop new ideas from floating in. They whisper their temptations and nudge your elbow and go on enticing you until at last you give way.

Something that all of us who post on Substack will recognise only too well!

Greengates - Persephone Books https://persephonebooks.co.uk/products/greengates

Looking forward to reading this later on today with a nice cup of tea!