Emily Young and 'William'

When the truth is more extraordinary than the fiction

In 1934, Allen Lane, a publisher working for the well-established firm of The Bodley Head, conceived an idea for a range of well-produced, high quality paperback books, to be sold at affordable prices at busy locations such as railway stations. He was impressed by the launch in Germany two years earlier of Albatross Books, and adopted many of the same design ideas – a standard size, not too big, a cover with smart, clean typography but no illustration, colour-coded for type of book – as well as an idea for a name, and in 1935 Penguin Books was born. Enormous care had to be taken in the selection of the launch titles – and Lane picked ten novels, all reprints, chosen for immediate appeal. He needed the books to fly off the shelves: and they did. Among his ten novels were works by Agatha Christie, Ernest Hemingway, Compton Mackenzie, Andre Maurois, and, last alphabetically on the list but not least, ‘William’, by EH Young.

William is an extraordinarily good novel, and quite deserved its place on Allen Lane’s list. It is as readable today as it ever was, for if its plot seems dated, its underlying subject - the impact on a family of the sexual transgressions of one of its members - is as relevant now as it was in the 1920s, when it was written. There may not be the same public reaction today to a marriage breaking down as there was in the years between the wars, but the ripples within the home can be just as damaging, just as revealing. Of course, if ever an author spent time observing the impact on a family of infidelity, it will be EH Young, whose private life was just as unconventional as that of the characters in her novels.

Emily Hilda Young was born in Whitley Bay, Northumberland in 1880, one of seven children, the daughter of a prosperous shipbroker. She went to school initially in Gateshead and later at Penrhos College, a Methodist boarding school in Colwyn Bay, North Wales. By 1900 the family had relocated to Sutton, Surrey, and in 1902 she married John Arthur Helton Daniell, a solicitor, and moved with him to the fashionable neighbourhood of Clifton, in his home town of Bristol. There she developed an interest in classical and modern philosophy, became a supporter of the women’s suffrage movement, took up mountaineering and, most importantly, started writing novels. Her first, A Corn of Wheat, was published in 1910.

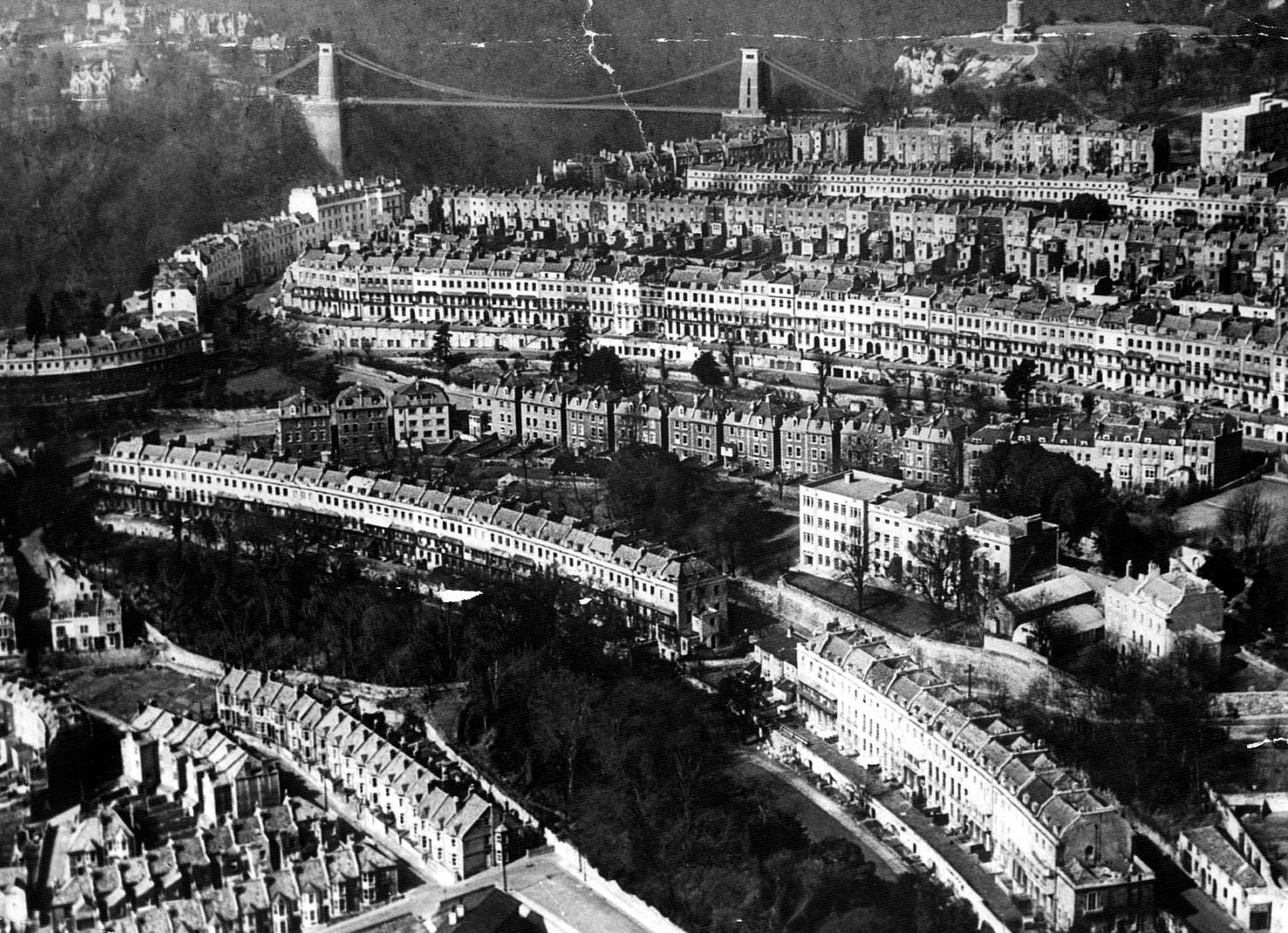

This is an aerial view of Clifton, a smart suburb of Bristol, high on the hill above the Avon Gorge, looking towards the Clifton Suspension Bridge. On one side of the river, above the busy port city, stand the grand houses, the leafy avenues, the parks, and a prestigious public school. Down below, hidden in this photograph, lie the docks and all the little businesses that support them. Across the bridge one can see the woods, meadows and pastures of rural Somerset. EH Young fell in love with Clifton, with its elegant terraces, its alleyways and cobbles, its view of the docks, the presence of the river flowing to the sea, and the surrounding countryside. In her novels she calls it Upper Radstowe, and the bridge is The Bridge - but the area has a personality that infiltrates all her novels - her characters cross the bridge to escape their difficulties; they enjoy the peace of the countryside, they take a steamboat ride, they walk home up the hill from the docks to the elegant terraces above, they watch the trees turn from spring blossom to autumn gold. I can think of several series of novels that all take place in the same setting, but Young is almost Hardy-esque in the way that the location plays a role in her stories.

It was not just Clifton that Emily fell in love with: at some point in the early years of her marriage she began an affair with Ralph Bushill Henderson - a married man, another keen mountaineer, a schoolteacher and a friend of her husband. Ralph, the son of a distinguished Baptist minister, was born in Coventry in 1880, and studied maths at New College, Oxford where he took a First. From 1901-1910 he taught maths at Bristol Grammar School, and in 1911 moved with his wife Beatrice to take up a post teaching maths and science at Rugby School.

If the move to Rugby might have been designed to end the affair, we have ample evidence that it was unsuccessful. The lovers continued to share a passion for climbing, even as Emily’s career as a novelist was taking off. On 14 August 1915, Emily Daniell, as she is still remembered in climbing circles, led Henderson and two other men on a pioneering route up the Idwal Slabs in northern Snowdonia. Previously thought impregnable, Henderson later testified to his lover’s “remarkable qualities of balance, speed, and leadership, and to her sound judgment of rock and route”. Originally christened “Minerva” in honour of feminine endeavour, the route is now better known as “Hope”. Young was a founder member of the women climbers’ Pinnacle Club in 1921. However, she climbed less frequently as her literary career flourished.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, both Emily’s husband John and her lover Ralph joined the same branch of the Royal Artillery Regiment, the Royal Garrison Artillery. Emily, who had no children to worry about, went to work, first as a stable groom and then in a munitions factory. Her husband John was killed on 1 July 1917 during preparations for the Third Battle of Ypres. Her lover Ralph served with great distinction, mentioned in despatches in 1916, and ended the war in France as Acting Lieutenant-Colonel.

In 1919, Ralph was appointed headmaster of Alleyn’s, a prestigious boys’ day school in Dulwich. Emily followed her lover and his wife to London, renting a flat in the same building, and taking up a post as school librarian at Alleyn’s. Throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, the telephone directory shows the threesome sharing accommodation: in Christchurch Road, Tulse Hill, when they are all at the same address, in 1925 in a house called Gosforth, College Road, and in 1939 the married couple are at 87 Sydenham Hill, and Emily is at 87a. Emily was known to the world as the widowed Mrs Daniell, and one can only assume that Mrs Henderson was prepared to accept this extremely shocking, unconventional state of affairs. In retirement, Henderson separated from his wife and Young moved with him to Bradford-on-Avon in Wiltshire. They never married but lived together in Wiltshire until Emily died from lung cancer in 1949. Among her other novels, I can recommend Miss Mole, republished not that long ago by Virago.

All of which brings us back to William, Young’s most commercially successful novel, which established her reputation as a great writer. First published in 1925, it sold nearly 70,000 copies and was reprinted 20 times before 1948. William and Kate Nesbitt are a wealthy couple living in one of the grander houses in Radstowe with their youngest, unmarried daughter Janet. They have three other daughters, all married, two (Mabel and Dora) to Radstowe businessmen, and one, Lydia, to a solicitor living in London. They also have a son, Walter - also married, living with his wife Violet in a flat nearby. Neither Lydia nor Walter have any children, and this is perhaps the only cloud in Mrs Nesbitt’s sky when the story opens - as she is a proud and mostly enthusiastic grandmother.

William Nesbitt has made his money in shipping - packet steamers that ply their trade in the Bristol Channel. He had begun life as a sailor, and still walks with ‘a slight and never-to-be-lost roll in is gait.’ We know that he is a romantic - the poems that he wrote for his wife are still hidden in her jewellery box. Their marriage of forty years is a strong and happy one. Young writes that to William, the sea ‘was like the presence of a woman, still beautiful, whom he loved no longer with desire but with knowledge, understanding and satisfaction. He breathed more deeply and happily because of it.’ That sentiment also stands for his marriage to Kate, ‘stout but comely’. And we know that much as he loves all his children, he adores Lydia. ‘He understood her sins and her sorrows.’

Meanwhile Kate’s whole life revolves around her children, but of course they have grown and left her behind. ‘She had given birth to five bodies and she would always be a stranger to their souls.’ She had not made the same fuss of her children growing up as her daughters did of theirs, probably because at the time she was also supporting William in his efforts to build a business, but now their concerns were her whole life. Yet, in case you should find all this a little too sentimental, I love Young’s ability to write honestly about motherhood - Kate is only too quick to spot the flaws in her children’s characters, and to criticise the choices they were making ‘She was hurt by her own capacity for finding fault in her children.’ She loves her grandchildren, because ‘they had not had time to develop unattractive qualities.’ Her eldest daughter Mabel has married John, a self-righteous deacon from the local chapel, who owns a successful timber business, and yet Mabel ‘preferred grievances to possessions’. Walter’s wife Violet also worries Kate: ‘the excessive powdering of her face vaguely suggested impropriety.’ Lydia has gone off to live in a damp, unattractive London flat, and Kate thinks she ‘should spend more time on her house. Why doesn’t she polish her furniture?’

Of course, it rapidly becomes clear why Lydia is not polishing her furniture. She has become bored with her marriage, and runs away with Henry Wyatt, a penniless poet. Kate’s world explodes! How will she ever hold up her head in Radstowe society again? Mabel and her husband are shocked to the core, Dora’s pompous husband Herbert declares that henceforth Lydia will be barred from the family, in case she contaminates his children. But William, lovely, kind William holds his ground, in such a well-written scene. Kate has summoned the family to a meeting, William arrives late:

He saw his family as a pack of hounds and Lydia as their quarry… As he entered the drawing-room where the lights were on but the curtains undrawn, the talking ceased. Mrs Nesbitt sat, with the effect of someone on a platform, in the high-backed chair which she usually avoided: her face was flushed, her lips compressed, and Mabel, with her hat at a still sharper angle, was sitting sympathetically near. Her hands were restless, her expression bitter but somehow satisfied, and now and then she glanced at John and jerked her chin as if to say ‘I told you so.’…John, who was planted firmly in his chair, had assumed the attitude acquired at stormy deacons’ meetings, the forbearance of a Christian… ‘You have all heard the news?’ [William] asked sharply, and a succession of bowed heads and sibilant monosyllables assured him of their knowledge. ‘Very well. I have this to say. I will not have my daughter’s actions criticized in my presence. Keep your condemnations and your speculations to yourselves. I’ll have none of them. Lydia’s affairs are her own,’

Mabel looked at John and John spoke. ‘Pardon me, Mr Nesbitt, but we are all members of one great community and we have the right - it is our duty - we are morally bound - to take a line.’

‘Take it,’ William Nesbitt said. ‘Take it. It’s a harmless amusement, but not in this house please.’

Lydia’s desertion of her husband rebounds across the whole family. The youngest daughter, Janet, decides to branch out on her own, much to her mother’s disgust:

‘She wants to go away and be trained as a social worker, one of those women who go to factories and interfere with the girls.’

Dora realises that her husband is an insufferable prig:

‘The fiction in this case,’ Dora elaborated, ‘is that one’s husband is always right.’ Mrs Nesbitt, with disapproval on her face, could still think bitterly, that her own husband was often wrong, but where she triumphed was in never saying so.

Throughout it all, it is William who refuses to blame his daughter, or be anything other than loving to her. ‘He trembled for her and was proud of her courage.’ As he says ‘The sanctity of marriage is an unholy thing. It’s not fair, it’s cruel, it’s a prison. If marriage remains holy, it’s a piece of good fortune; if it doesn’t, who dare say the parties to it are wicked.’ Very wise words, and perhaps a surprising sentiment for a respectable businessman and pillar of society in the 1920s.

The life chosen by Ralph Henderson and Emily was fraught with danger. They had both been brought up in strict non-conformist households; now they were breaking every code, social, moral and religious. Any hint of scandal would have made it impossible for Ralph to hold down his career as a headmaster at a public school. A divorce, similarly, would have finished him. Emily seems to have had the good fortune that her family did not turn on her for her improper behaviour. The scandal never leaked out. I think that she wrote this novel as a tribute to the love and support she had received - certainly from one member of her family. Emily Young’s father was a shipbroker who did well in business, having started life as a merchant seaman. He died a very wealthy man in 1923, just two years before this novel was published. He named his daughter Emily as one of his three executors. His name was William.

This is fascinating. I have never read anything by Emily Young. I will look out for a copy. Sarah, I also have to say that I have just finsihed your Literature for the People and have enjoyed it more than any non-fiction book I've read in years. Wonderful!

What a great story...well-researched and impeccably told! Thank you😊