In my circumnavigation of the authors featured on the cover of my biography of the Macmillan Brothers, there is only Matthew Arnold and Alfred Lord Tennyson left to write about - but I thought I would delay gratification and surprise you with the wife of the Poet Laureate, Emily Tennyson.

When I started researching the relationship between the Tennyson family and the House of Macmillan, I realised that I had in fact met Emily twice before, but in fiction: once by name, and once under a gentle disguise. She is the obvious source for the wife of the poet Randolph Ash in AS Byatt’s masterpiece, Possession. For most of the book, she is a shadowy figure, hardly mentioned in the conversations between Ash and his beloved Christabel LaMotte, but Ellen Ash emerges from the shadows in the touching final chapters, playing a crucial role in the plot. For all their married life Ellen has acted as Randolph’s secretary, his amanuensis, and his protector from the public. Now she has to decide which of his papers to keep, and which to burn, and which of his secrets he shall take with him to the grave.

When he was lying there he said, ‘Burn what they should not see’ and I said ‘yes’, I promised. At such times it seems a kind of dreadful energy comes, to do things quickly, before action becomes impossible…There are things here I cannot burn. Nor ever I think look at again. There things here that are not mine, that I could not be a party to burning. And there are our dear letters, from all those foolish years of separation. What can I do? I cannot leave them to be buried with me. Trust may be betrayed. I shall lay these things to rest with him now, to await my coming. Let the earth take them.

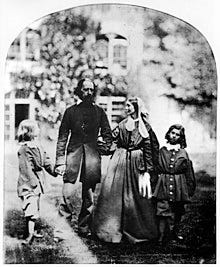

There is much in Byatt’s depiction of Ellen Ash to remind one of Emily Tennyson, including the painful long wait, thirteen years, between when the couple first met and when Alfred was successful enough to be allowed to marry her. But where Ellen Ash is unable to consummate her marriage with Randolph, Emily Tennyson gave birth to two sons, Hallam and Lionel, who were her pride and joy.

In Lynn Truss’s delightful, funny, clever book Tennyson’s Gift , Emily is the fierce, comical protector of her over-sensitive husband, tearing up unpleasant fan mail and burning bad reviews.

At Farringford, Emily Tennyson sorted her husband’s post. Thin and beady-eyed in her shiny black dress, she had the look of a blackbird picking through worms. She spotted immediately the handwriting of Tennyson’s most insistent anonymous detractor (known to the poet as ‘Yours in aversion’) and swiftly tucked it in her pocket. Alfred was absurdly sensitive to criticism, and she had discovered that the secret of the quiet life was to let him believe what he wanted to believe - viz, that the world adored him without the faintest reservation or quibble. To this comfortable illusion of her husband’s, in fact, she was steadily sacrificing her life.

The real Lady Tennyson was born Emily Sellwood in 1813, the oldest of three daughters, and raised by her lawyer father after her mother died when she was very young. She came from a prosperous Lincolnshire family: her uncle was the fated polar explorer Sir John Franklin. She met Alfred when her sister Louisa married his brother Charles, but in 1836, he was just an impecunious poet with troubling religious views, and there were many reasons not to marry. They finally married in 1850 when she was 37, and he had just made his name with the publication of In Memoriam. In fact, the public adulation of the man became overwhelming and the couple retreated to Farringford, or as Lynn Truss describes it, ‘a neo-Gothic bunker in the farthest corner of the Isle of Wight.’

It was Emily who was responsible for helping the up-and-coming publisher Alexander Macmillan strike up a friendship and eventually a long and profitable business relationship with her husband. In 1856 the sculptor and friend of the Tennyson family, Thomas Woolner, had been given the opportunity to make a bust of the poet. Emily loved the finished article, particularly because it showed Tennyson without a beard, (apparently she was never happy about his facial hair), and hoped that it could be put on display at his old college, Trinity, in Cambridge. Unfortunately, the College authorities were unimpressed with this suggestion, so Woolner suggested asking his friend Macmillan, who lived in Cambridge and was becoming well-known among academic circles, to do some tactful lobbying. When he succeeded, Emily wrote to Macmillan to thank him and invited him to stay at Farringford. As Macmillan was at that very moment putting together plans to launch a monthly magazine, he jumped at the chance, and returned from the Isle of Wight with the promise of a poem from the poet. But it was Emily with whom he found himself negotiating.

Tennyson’s principal publisher was Moxon, and Emily, who regularly acted as her husband’s literary agent, was nervous about breaching the contract with Moxon, and was also juggling competing requests from other periodicals. Macmillan was too respectful of long-term publishing partnerships to attempt to dislodge Moxon completely, but a poem for the Magazine seemed achievable. Alexander’s thank you letter of 11 October 1859 to the poet shows the extent to which he was prepared to promote his cause, but also that he recognised that there was more than one person to be propitiated:

I can now say unreservedly that we shall be most glad to have your Idyll for our Magazine . . . I hope Mrs Tennyson will feel satisfied that a poem of this length will be more appropriate to our graver monthly than to the lighter weekly, which I trust you will find able also to gratify with some smaller piece.

Enclosed with this letter were gifts of three small books for the Tennyson boys, and copies of the latest works from Maurice and Henry Kingsley. He also wrote to Emily:

It will be an inexpressible delight for me to be in any way connected as a publisher with Mr Tennyson – gratifying to my vanity I fear I must honestly admit – perhaps a little of some better feeling mingles with it, and commercially I think it will do our magazine a great deal of good.

Macmillan offered the extremely generous sum of one pound a line to Tennyson, and ended up paying £300 for the poem, Sea Dreams. Keen to get maximum public notice for this coup, he asked Tennyson if he could add as a subtitle ‘An Idyll’, since the public were waiting with bated breath for more Arthurian Idylls from the Poet Laureate. The poem featured in the January 1860 issue of Macmillan’s Magazine, timed to act as a distraction from the launch of Thackeray’s Cornhill. Thereafter, Macmillan often wrote to Emily as well as to her husband, discussing publishing business, but always enquiring after the boys and sending books he thought they would enjoy.

Many who visited Farringford, or the Tennysons’ second home at Aldworth near Haslemere, were sympathetic to what Emily had to put up with. Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol, wrote to Florence Nightingale in 1867:

He is also so utterly unpractical and (not altogether from selfishness) so intensely egotistical, as at times to be insupportable; you feel at the same time that there is a noble element in him. She is a saint, a sacred person, who can never be spoken of as highly as she deserves, but she has not self-love to keep herself alive.

The enormous effort of caring for Alfred, hosting his numerous visitors, bringing up his two sons, and acting as his proofreader, agent and business manager, certainly did little for Emily’s health, and for many years she was an invalid confined to the sofa or a wheelchair, but she outlived her husband and helped her only surviving son Hallam write his biography. She died in 1896. Anne Thwaite wrote a lengthy and warm appreciation of her, published on the centenary of her death: Emily Tennyson: The Poet’s Wife. She quoted Philip Larkin’s poetic tribute:

Mrs Alfred Tennyson

Answered/begging letters/admiring letters/ insulting letters/enquiring letters/ business letters/and publishers' letters.

She also/looked after his clothes/saw to his food and drink/ entertained visitors/protected him from gossip and criticism.

And finally/(apart from running the household)/ Brought up and educated his children.

While all this was going on/Mister Alfred Tennyson sat like a baby/Doing his poetic business.

Of course, it is easy to characterise or even dismiss Emily as a poor, downtrodden wife with no life of her own, subsumed into the greater glory of her husband’s genius. Yet there is no evidence either that she felt that way about herself, or indeed that there was anything better or more important she could have done with her talents than be an exceptional business manager and the energetic supporter of a man who needed all the domestic help he could get. Annie Fields, wife of JT Fields the Boston publisher, wrote of Emily that ‘her poet’s life was her life, and his necessity was her great opportunity.’ There weren’t many great opportunities for women in Victorian England, and I choose to assume that at the age of thirty-seven, Emily Sellwood was quite capable of choosing the best and most interesting life she could, however exhausting it might turn out to be.

I wrote a biography of Julia Margaret Cameron and she was a big fan of Emily. Somewhere there’s a quote (from her journals?) of Emily writing “words is enigmas.” Who knows why?? But I love the enigma of her saying it, and its grammar--

I really loved this - I was gearing myself to be angry on behalf of Lady Tennyson until your last paragraph. Such a nuanced look at her role in Alfred (Lord Alfred's) life!