It is well-known that research takes you down rabbit holes, and here I am down a madriguera del conejo… Readers will know that I picked up a copy of Laurie Lee’s memoirs just to get a flavour of inter-war life growing up in a Gloucestershire village, but his lush prose soon had me entranced, and I followed him all the way to Spain.

In the second volume of his memoirs, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, we follow the 19 year old Laurie from Slad as he sets off on foot for Spain, via Southampton and London. He arrived in Vigo in July 1935, and slowly worked his way south, supporting himself by busking with his violin. He found a desperately poor country, and although he had certainly witnessed poverty and unemployment in the rural Cotswolds, this was of a different character:

Spain was a wasted country of neglected land - much of it held by a handful of men, some of whose vast estates had scarcely been reduced or reshuffled since the days of the Roman Empire. Peasants could work this land for a shilling a day, perhaps for a third of the year, then go hungry.

All of Laurie’s Spanish experiences make fascinating reading, but it is after he has settled in a small fishing village on the south coast, Almunecar, that the slow slide to civil war begins, and here I think Lee’s writing shifts gear. I found it deeply moving. I am certainly no expert on Spanish politics, but as I understand it, in the five years after 1931 when the King had fled Spain, increasing hostility between Socialists and Fascists, aggravated by the Depression, led to violence and severe political instability. Lee writes:

In February (1936) came the Election, with a victory for the Socialists. This was not deliverance, merely a letting up of confusion. An end to years of listening and waiting for something to happen. Suddenly everything was out in the open. A Popular Front, they said, a People’s Government at last.

The election and change of government seemed to usher in a wave of freedom, of ‘new found liberties’ especially for younger people, as the power of the oppressive Catholic church began to be curtailed:

There were also other freedoms. Books and films appeared, unmutilated by Church or State, bringing to the peasants of the coast, for the first time in generations, a keen breath of the outside world…the brief clearing away of taboos, which seemed to possess the village.

Slowly but surely as the summer approaches, the tension mounts, and Lee’s prose is weighted with anticipation:

The weeks leading towards summer were hot and steely, and except for the radios in the bars, crackling with political speeches, the village seemed entirely cut off from the world…a slow brew of expectation simmered over the houses, raising poisonous bubbles that exploded every so often in little outbreaks of irrelevant violence.

Almunecar was a village solely dependent on offshore fishing and sugar canes. The landowners treated the agricultural labourers like peasants, the fising stocks were rapidly depleting: not surprisingly, Lee was living in a village full of angry men desperate for change. The ice plant, and then the power station were blown up, and ‘in spite of the inconvenience, everyone seemed to enjoy these gestures and the whiff of dynamite was considered a tonic’. By mid-May, the news from Madrid was growing more threatening and vague, there were strikes and parades, ‘clenched fists and slogans’. In Almunecar, rival factions developed and were only too happy to adopt the labels of Communist (with a long history of noble struggle behind it), or the new-fangled, fashionable Fascist. The church was set on fire, the tax collector and his family were driven out of town.

This to me is the power of Lee’s book - to concentrate the narrative of a descent into civil war into one small community makes it easier to imagine, and to comprehend.

June came in full blast, with the heat bouncing off the sea as from a buckled sheet of tin.

And then the murders began…a spray of bullets in a bar, flies circling over a young man’s body in a ditch.

It started in the middle of July. There were no announcements, no newspapers, just a whispering in the street amd the sound of a woman weeping…the fields emptied and peasants poured into the village, bringing their wives and children, their sheep and goats, and settling themselves down under the castle walls.

Word came that at nearby Altofaro a Fascist flag had been raised, so off drove four trucks filled with local militia to attack the rebels.

About noon, a white aircraft swung in low from the sea, circled the village amd flew away again - leaving the clear blue sky scarred with a new foreboding above a mass of upturned faces.

That evening, a destroyer appeared in the bay, and began to probe the coastline with a searchlight. The villagers panicked, and with nowhere to run, crowded onto the beach. Such pitiless brightness had never lit up their night before: friend or foe, it was a light of terror. The ship began to shell the beach, destroying houses, killing people, half a dozen salvoes….and then moved off, a case of mistaken identity, the Captain sent his apologies, he thought he was firing at Altofaro.

The villagers seemed to take this in good part, a sign that the war was real and that they had a part to play. Every tower and roof now proudly flew a red flag, and, in the passage that brings a tear to my eye:

This was the day when the peasants and fishermen openly took over the village, commandeering the houses of suspects and the empty villas of the rich and painting across them their plans for a new millennium. ‘Here will be the Nursery School.’ ‘Here will be the House of Culture.’ ‘Here will be a Sanatorium for Women.’ ‘Workers, Respect this House for Agricultural Science.’ ‘Here will be a Training College for Girls.’ Each of the large bold words was painstakingly written in red, a memoranda of a brief and innocent euphoria. For who among the crowds could guess, as they gathered in the streets to read them, that these naive hopes would later be treated as outrage?

Later that evening, the trucks of militia return, bringing bodies of the dead and wounded. The village became aware that night, not for the first time in its history, that a people’s army could be defeated.

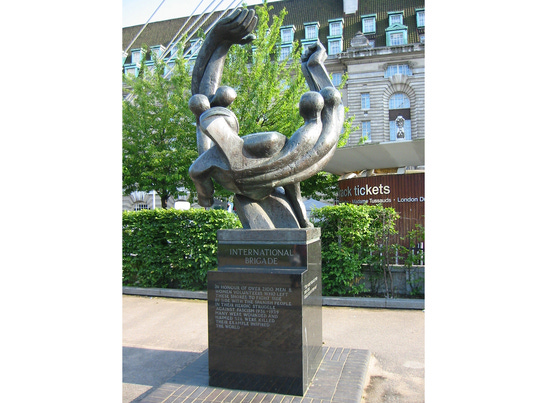

This volume of memoirs ends shortly afterwards, with Lee’s evacuation from the village courtesy of the British Navy. But, of course, driven by guilt and shame, and a sneaking desire to look more impressive to the several women in his life, late in 1937 Lee returned to Spain, crossing the Pyrennees on foot to join the International Brigade. The final volume of his memoir, A Moment of War, was published very late in his life, after his contemporaneous diaries had been stolen, and there is now dispute about how much of his story is accurate and how much a novelist’s myth. Valerie Grove, in her beautifully written biography, Laurie Lee: The Well-loved Stranger, established that he was indeed nearly shot as a spy, possibly on more than one occasion, and that he did make it as far as the International Brigade, but had to be invalided home pretty quickly. ‘Comrade, we are sending you back to London, you’re not much help to us here.’

To the writers and poets of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales: The equivocal attitude, the Ivory Tower, the paradoxical, the ironic detachment, will no longer do. Are you for, or against, the legal government and the people of Republican Spain? Are you for or against Franco and fascism? For it is impossible any longer to take no side.

Published in the Left Review 1937, and signed by Auden, Spender, Pablo Neruda and others.

When Lee finally came across the International Brigade:

We were an uneven lot: large and small, mostly young, hollow-cheeked, ragged, pale, the sons of depressed and uneasy Europe…part of the skimmed milk of the middle-Thirties…But confused as we were as we marched about, there seemed to be a growing urgency in our eyes…We shared something else, unique to us at that time - the chance to make one grand, uncomplicated gesture of personal sacrifice and faith which might never occur again. Certainly, it was the last time this century that a generation had such an opportunity before the fog of nationalism and mass slaughter closed in.

There was nothing romantic about the Spanish Civil War, or its inevitable outcome. Franco was backed with money and armaments by Hitler, and was happy for his country, and his countrymen and women, to be used as a ‘test bed for the hardware of the Nazi war machine’, as put by Edward Heath, who visited Barcelona as a guest of the Republicans in 1938. Lee said that he wrote A Moment of War out of guilt that he had survived. At one point he describes being given a desk job, filling out card index files of 500 or more British and Irish volunteers, more than half of them killed or missing.

Public schoolboys, undergraduates, men from coal mines and mills, they were the ill-armed advance scouts in the, as yet, unsanctified Second World War. Here were the names of dead heroes, piled into little cardboard boxes, never to be inscribed later in official Halls of Remembrance. Without recognition, often ridiculed, they saw what was coming, jumped the gun, and went into battle too soon.

I loved reading your piece on Laurie Lee's memoirs. Your vivid descriptions of his journey through Spain truly bring his experiences to life. The way you capture the tension and atmosphere leading up to the Civil War is incredibly moving. Fantastic job, I couldn't stop reading.

I feel like I should give As I Walked Out… another read, it's been a long time (best part of 50 years).

I've also crossed the Pyrenees on foot, and had a fascinating encounter with a shepherd who came by my tent still quite high on the Spanish side. He didn't speak any English and my Spanish was rudimentary, but when he realised I was British he started talking about collies, which are obviously the best dogs. Though this seemed a bit hard on the dog he did have. And he seemed to approve of King Juan Carlos, who was still relatively new then but steering Spain back towards democracy after the death of Franco. Which marks some sort of resolution to the Civil War and its aftermath.