By the mid-1930s, the voices of left-of-centre politicians were becoming increasingly frustrated that despite their best efforts, socialism was not gaining ground in Britain. The Consevative party continued to dominate the coalition ‘National Government’ which had been formed, after the collapse of Ramsay Macdonald’s Labour administration, to deal with the economic crisis of the Great Depression. Conditions among the poor continued to deteriorate as unemployment and stagnation laid waste to vast areas of the country: meanwhile it was perceived that the League of Nations was failing to counteract the rise of dictatorships and fascist governments across Europe, with the spectre of further war looming on the horizon.

Victor Gollancz (1893-1967) had established his own publishing company in London in 1927, publishing writers such as Ford Madox Ford, AJ Cronin, Dorothy L Sayers and George Orwell. He aimed to attract attention with his distinctive covers: bright yellow jackets, black and magenta text.

But publishing was not his only interest: Gollanz was a humanitarian, who defined himself as a Christian Socialist. It makes me very happy that his company was housed in Henrietta Street in Covent Garden, just a few doors along from the premises where Alexander Macmillan, also a Christian Socialist, had established his first London office. In 1931 Gollancz joined the Labour Party, and began to spend increasing amounts of his time discussing the state of the nation with other left wing thinkers, particularly GDH Cole, Sir Stafford Cripps, John Strachey and Harold Laski. But how could they spread the messages of socialism across the country? They found that when they published left wing political texts, it was hard to get them distributed, booksellers were wary about stocking them. However, Gollancz was a man of enormous energy and practical determination, and much like Alexander Macmillan, he believed that access to cheap but well-produced literature was the way to educate and inspire the working classes.

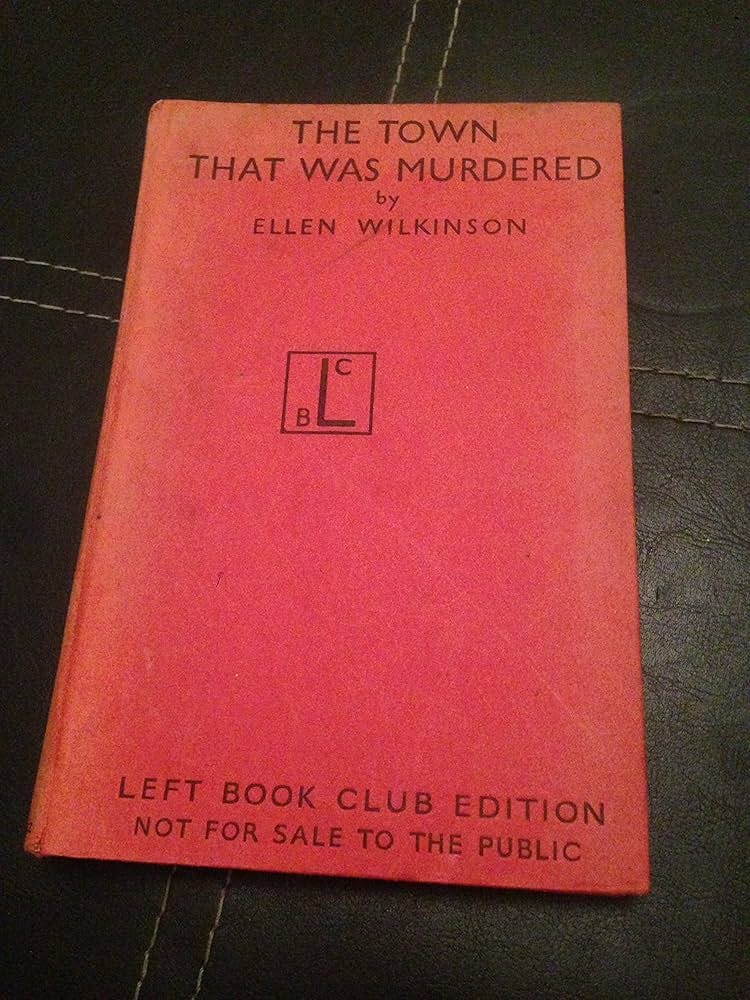

The Left Book Club was founded in May 1936. Its aim, according to Margaret Cole, was to produce ‘a series of books dealing with the question of fascism, the threat of war, and poverty - aiming at effective resistance to the first, prevention of the second, and socialism as a cure for the third.’ The books were to be selected by Gollancz, Laski and Strachey, and published as cheaply as possible, one a month, on the old-fashioned subscription basis, beloved of Victorian publishers such as Macmillan - in other words, buyers signed up in advance of the book’s publication, effectively underwriting the cost. The first book to be advertised in this way was France Today and the People’s Front by Maurice Thorez. The aim was to attract 2,500 ‘members’ of the Club: in fact, more than 5,000 people subscribed and by the end of the year the Club had 20,000 members. The launch title was hardly one to attract the frivolous reader: Gollancz was right to believe that there was an untapped audience out there, anxious to understand more about the extraordinary rather frightening times in which they were living. Or, as he put it, ‘The hunger of workers for good political literature’. Each book was new, never published before, in cheap paper covers: it was simultaneously published in hard back for general retail at four or five times the price.

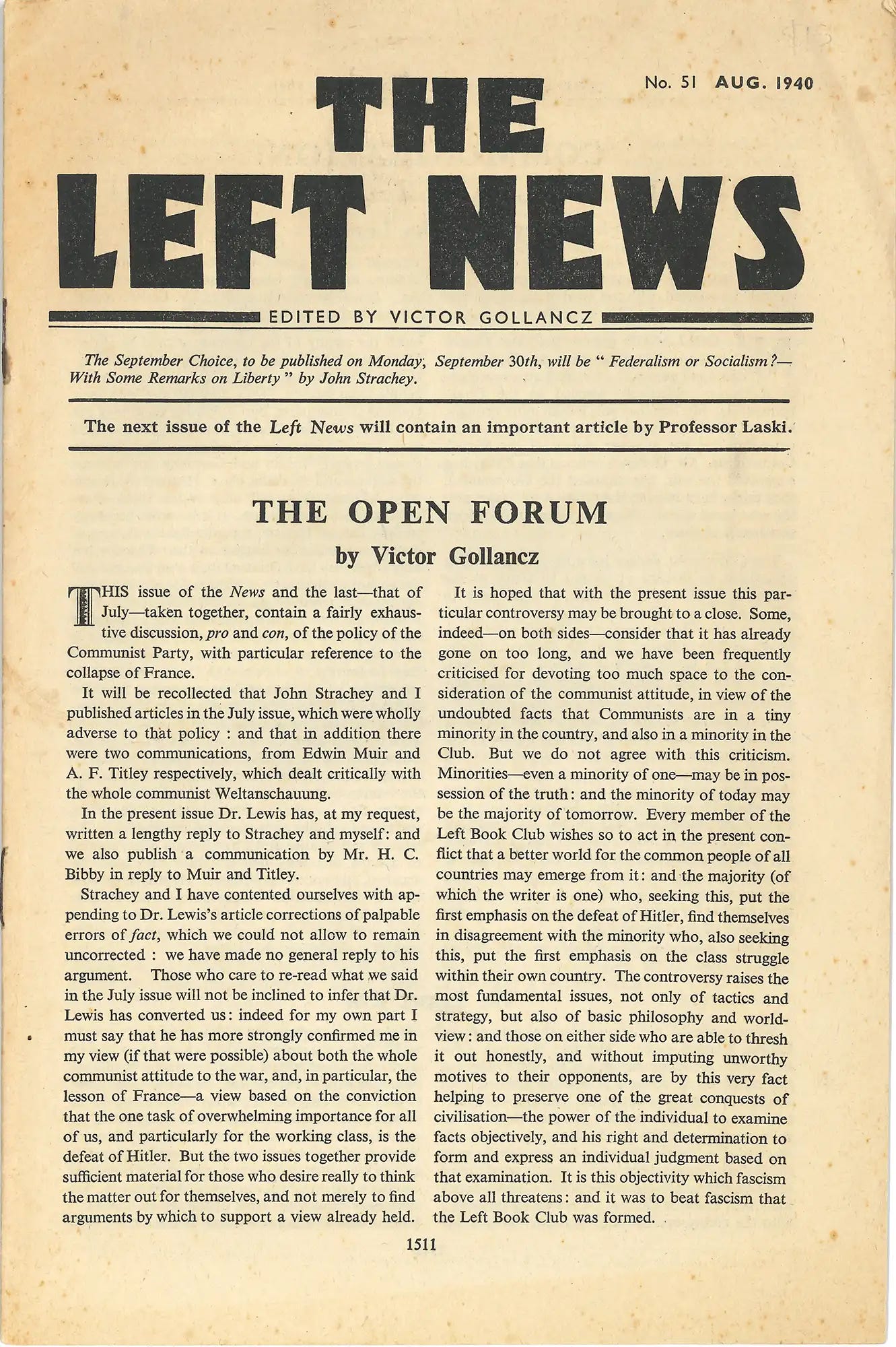

The Left Book Club took off in a way that surprised and delighted its founders, and in ways that had not been anticipated. Even though the books were cheap, many readers preferred to join a local group and share a subscription, which could then be combined with a monthly, or even weekly, discussion group. Club members also received a monthly newsletter which reviewed the book in question, as well as providing essays and contributions of topical interest: these were often written by Gollancz himself, staying up late into the night to perfect the wording, or to create the full page advertisements which did so much to publicise the Club.

In February 1937, the membership was treated to a rally at the Royal Albert Hall, addressed by Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party. Public meetings were held across the country, addressed by men and women from across the political spectrum: Gollancz believed, as Macmillan had, in free speech, in debate, in putting all the facts before the public and letting them decide for themselves. The Club was not tied to any political party: Nye Bevan and Ellen Wilkinson of the Labour Party might find themselves speaking alongside Bob Boothby, a Tory, Harry Pollitt, a Communist, and Eleanor Rathbone, an independent. The membership grew and grew - peaking at 57,000 in April 1939. Demand for more books grew - Supplementary, or optional, volumes were produced for keen readers.

Better known titles included Attlee’s The Labour Party in Perspective, Dr Griffiths’ Modern Marriage and Birth Control, Arthur Koestler’s Spanish Testament, and most famously, in March 1937, Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier. Strachey himself produced The Theory and Practice of Socialism, perhaps the most influential book ever published by the Club, with 250,000 copies produced and sold at tuppence. The members set up walking groups, debating societies, cycling groups, drama and film clubs. By 1938 the Club was organising two-week summers schools at Digswell Park, Welwyn.

It all seemed to be going so well: but events in Europe, and the different reactions they provoked among left-wingers in Britain, would create forces too strong for even Gollancz’s extraordinary personality to bind together. The first problem was the innate hostility within the trade unionist wing of the Labour Party to Communism and the Soviet Union. Although in the early days of the Club Attlee, Bevan and others had been supportive, they became increasingly hostile to the presence of Harry Pollitt on the platforms, and suspicious of John Strachey, previously a Labour MP who flirted with Communism but never joined the Party.

The main problem was that the Left simply could not agree on how to avoid another war. Back in the 1920s, pacifism and faith in the League of Nations to settle international disputes without recourse to war had seemed a simple solution. But Japan’s aggression in the Far east, Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia, and then the open interference by the Nazis and the Soviets in the Spanish Civil War, proved too much for the League. Gollancz and his friends moved from pacifism to horror at the rise of miltarism in Europe. They began to argue that the only way to avoid another war was to stand up to Hitler: the opposite of the Appeasement policy being pursued by Neville Chamberlain and the National Government. They desperately hoped that an alliance could be formed between Britain, France and the Soviet Union which might lead to the overthrow of the Nazis. The announcement of the Russo-German pact in 1939 put an end to this forlorn hope, and marked the beginning of the end for The Left Book Club. A symptom of the disintegration of the left wing alliance was the publication in 1940 of Leonard Woolf’s Barbarians at the Gate, openly critical of the Soviet Union, and of the Communists in general.

The outbreak of war was the final death knell for much of the life of the Club - social meetings became impractical, and conscription meant that the hard core of the membership, the working and middle class man, disappeared. John Strachey rejoined the Labour Party after the fall of Holland, and in 1945 would join Attlee’s Government as a Minister. However, the influence of the Left Book Club survived. The dispersal of the membership throughout the British Forces across the theatres of war may well have led, via Education Officers and informal discussion groups, to the landslide Labour victory of 1945. 131 MPs elected in 1945 had been Club members.

Gollancz wound up the Left Book Club in 1948, although today another group operates in tribute to the founder’s original aims. Gollancz never stopped campaigning: he rapidly became consumed with fear and fury over the fate of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. After the war he led a commission which culminated in the founding of the charity War on Want. He also campaigned against capital punishment. His publishing company survives as an imprint of Orion Publishing. He should be better remembered, and celebrated, today.

What a great piece. VG's story is another book waiting to be written - do you think?

your article beautifully captures the significance of Victor Gollancz’s vision and relentless drive. I was struck by how you conveyed the urgency and hope surrounding the Left Book Club’s inception. Your description of the Club as a collection of books and a movement for education and change is compelling. You did a wonderful job shedding light on this lesser-known history chapter with clarity and insight.